A new method of pain assessment that uses artificial intelligence could offer a way to eliminate racial bias from the process, according to a new study.

Among the many mysteries in medical science, it is known that minority and low-income patients experience greater pain than other parts of the population. This is true regardless of the root cause of the pain and even when comparing patients with similar levels of disease severity.

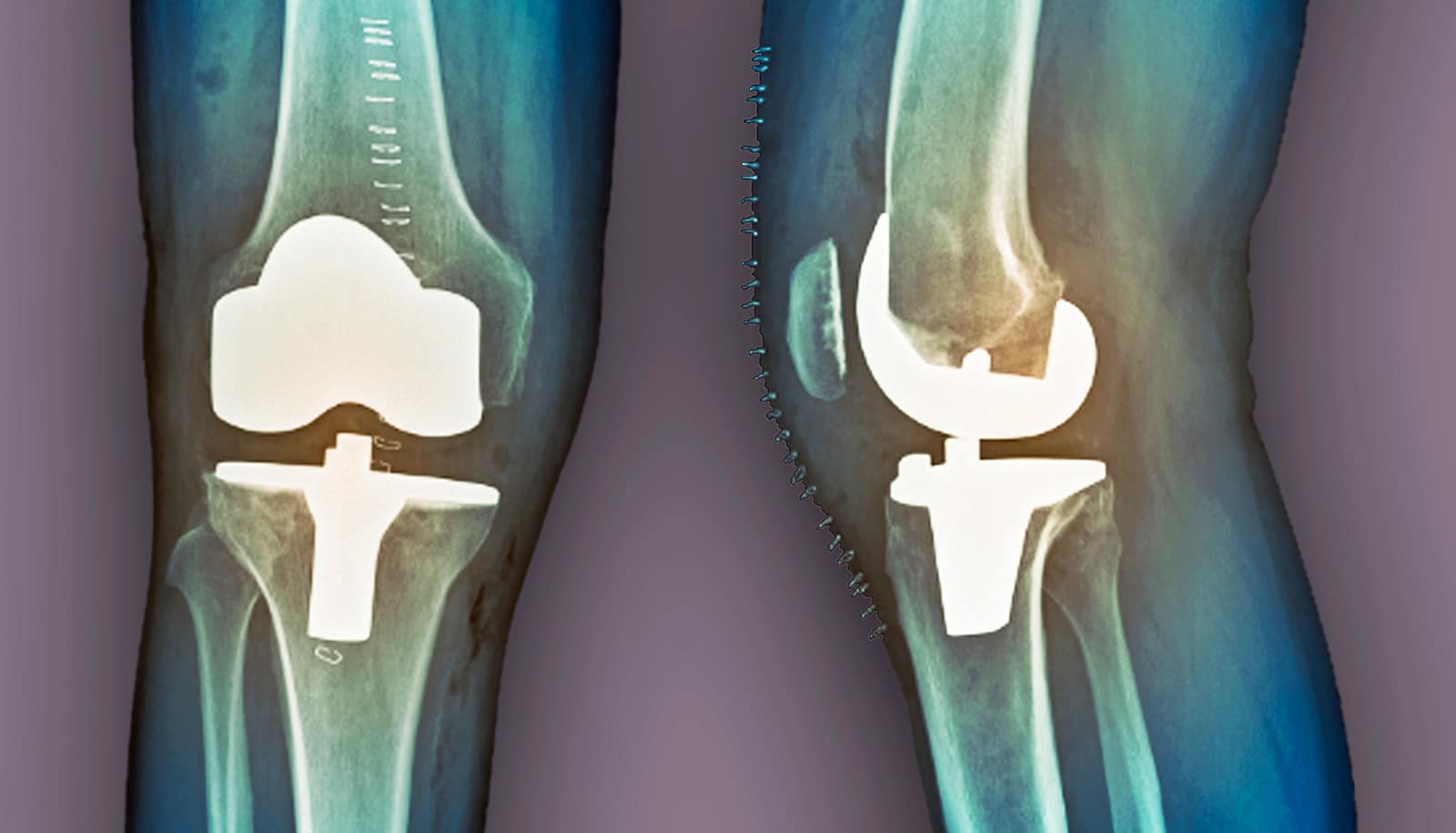

As reported in Nature Medicine, researchers show that AI can more accurately and more fairly measure severe knee pain.

Today, when patients with knee pain visit the doctor, the severity of their osteoarthritis is rated on what is known as the Kellgren and Lawrence Grade (KLG). However, even for two patients with similar osteoarthritis and the same KLG score, low-income populations report more pain. Consequently, the underserved fail to qualify for knee-replacement surgeries and are more often treated with risky opioid painkillers.

More accurate, fair knee pain assessment

The racial/socioeconomic pain disparity in KLG scores has even led some to wonder: Perhaps the pain is not solely caused by injury, but is being made worse by other factors not in the knee, such as stress.

To answer that question definitively, researchers developed a machine-learning algorithm to show that the standard radiographic measures of pain used today—namely KLG—may overlook certain features of injured knees that cause pain.

What’s more, these biases unfavorably and disproportionately affect how pain is treated in underserved minority and low-income populations. The new algorithmic approach evaluates patient X-rays and quantifying pain levels much more accurately—and more fairly.

“By using X-rays exclusively, we show the pain is, in fact, in the knee, not somewhere else,” says Jure Leskovec, a computer scientist at Stanford University. “What’s more, X-rays contain these patterns loud and clear but KLG cannot read them. We developed an AI-based solution that can learn to read these previously unknown patterns.”

Were the pain not in the knee itself, adds Leskovec, a Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence faculty member, even AI would fail to capture it.

It turns out, that KLG overlooks these patterns and doesn’t accurately “read” pain from the objective criteria in the knee. The bottom line is that AI can remove the bias in the way knee pain is measured and, by extension, how it is treated. Consequently, more minority and low-income patients would qualify for knee-replacement surgeries.

Accurate predictors

Leskovec and colleagues began with a diverse database of over 4,000 patients and more than 35,000 images of their damaged knees. It included almost 20% Black patients and large numbers of lower-income and lower-educated patients.

The machine learning algorithm then evaluated the scans of all the patients and other demographic and health data, such as race, income, and body mass index, and predicted patient pain levels.

The team was able to then parse the data in various ways, separating just the Black patients, for instance, or looking only at low-income populations, to compare algorithmic performance and test various hypotheses.

The bottom line, Leskovec says, is that the models trained using the diverse training data sets were the most accurate in predicting pain and reduced the racial and socioeconomic disparity in pain scores.

“The pain is in the knee,” Leskovec says. “Still useful as it is, KLG was developed in the 1950s using a not very diverse population and, consequently, it overlooks important knee pain indicators. This shows the importance to AI of using diverse and representative data.”

Knee pain ‘heat maps’

Leskovec notes that AI will certainly not replace the physician’s expertise in pain management decisions; rather, he sees it aiding decisions. The algorithm not only scores pain more accurately but presents additional visual data that could prove helpful in the clinic such as “heat maps” of areas of the knee pain most affects that might help physicians notice problems not apparent in the KLG evaluation and, for instance, choose to prescribe fewer opioids and get knee replacements to more patients in these underserved populations.

As Leskovec’s work shows, artificial intelligence balances inequalities. It more accurately reads knee pain and could greatly expand and improve treatment options for these traditionally underserved patients.

“We think AI could become a powerful tool in the treatment of pain across all parts of society,” Leskovec says.

Additional coauthors are from Harvard University; the University of Chicago; the University of California, Berkeley; and Stanford.

Source: Stanford University