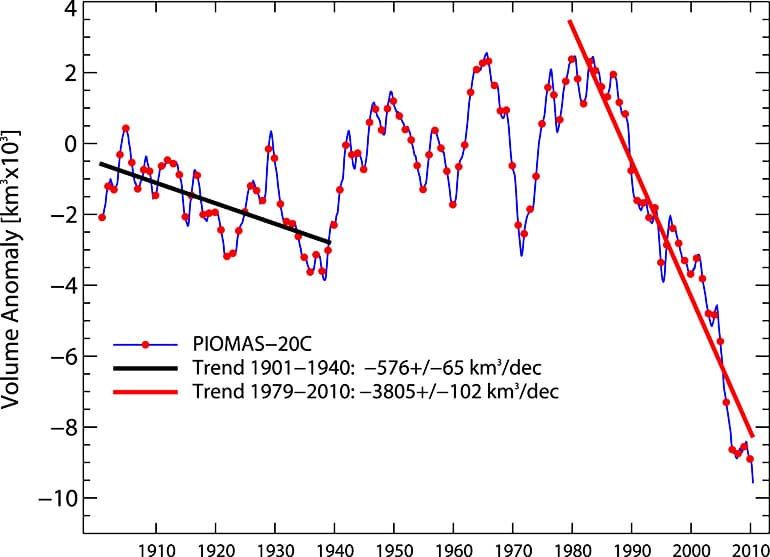

Modern-day computer simulations and historic observations from 100-year old ship logbooks have extended estimates of Arctic sea ice volume all the way back to 1901, researchers report.

The Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean and Modeling System, or PIOMAS, is a leading tool for gauging the thickness of sea ice coverage in the Arctic Ocean. Until now, that system has gone back only as far as 1979, when satellites began imaging the sea ice from above.

“This extends the record of sea ice thickness variability from 40 years to 110 years, which allows us to put more recent variability and ice loss in perspective,” says first author Axel Schweiger, a sea ice scientist at the Applied Physics Laboratory at the University of Washington.

“The volume of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean today and the current rate of loss are unprecedented in the 110-year record,” he adds.

PIOMAS provides a daily reconstruction of what’s happening to the total volume of sea ice across the Arctic Ocean. It combines weather records and satellite images of ice coverage to compute ice volume. It then verifies its results against any existing thickness observations. For years after 1950, that might be fixed instruments, direct measurements, or submarines that cruise below the ice.

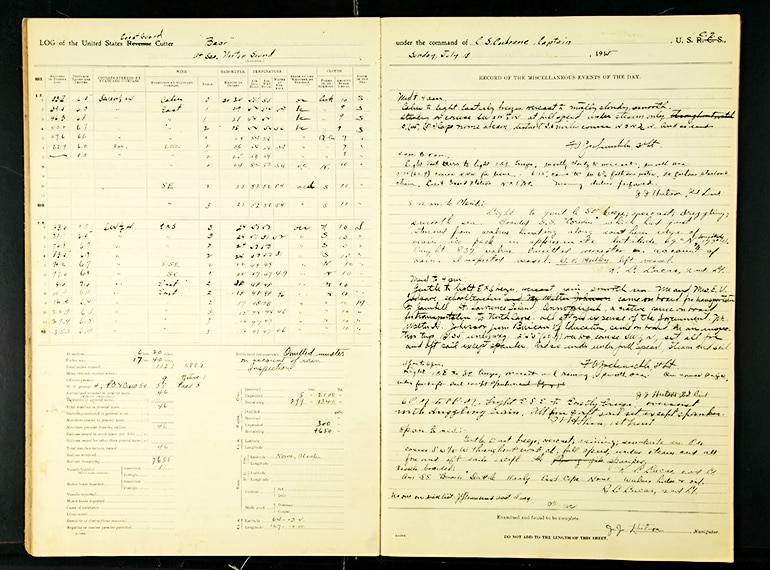

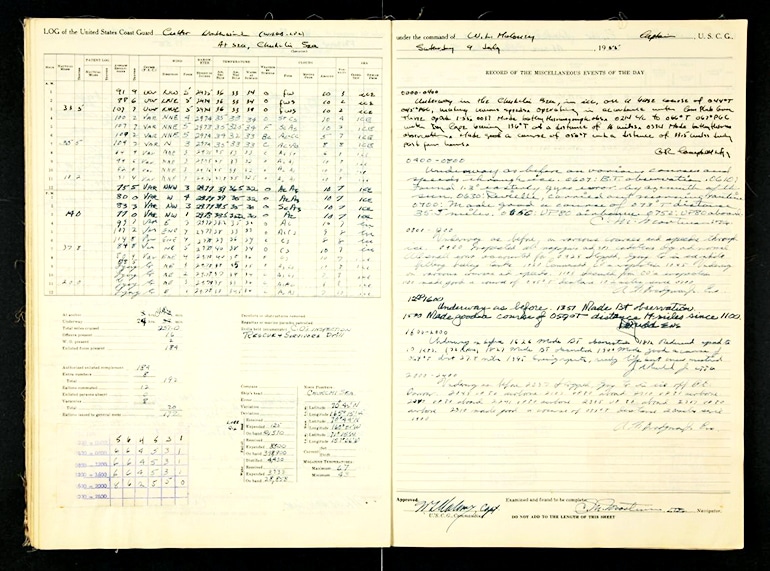

During the early 20th century, US Revenue cutters, the precursor to the Coast Guard, and Navy ships that have cruised through the Arctic each year since 1879, made rare direct observations of sea ice. In the Old Weather project, researchers have been working with citizen scientists to transcribe the weather entries in digitized historic US ships’ logbooks to recover unique climate records for science. The new study is the first to use the logbooks’ observations of sea ice, some written by hand in the early 1900s.

“In the logbooks, officers always describe the operating conditions that they were in, providing hourly observations of the sea ice at that time and place,” says coauthor Kevin Wood, a researcher at the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean.

If the ship was in open water, the logbook might read “steaming full ahead” or “underway.” When the ship encountered ice, officers might write “steering various courses and speeds” meaning the ship was sailing through a field of ice floes. When they found themselves trapped in the ice pack, the log might read “beset.”

These logbooks until recently could only be viewed at the National Archives in Washington, DC, but through digital imaging and transcription by Old Weather citizen-scientists these rare observations of weather and sea ice conditions in the Arctic in the late 1800s and early 1900s have been made available to scientists and the public.

“These are unique historic observations that can help us to understand the rapid changes that are taking place in the Arctic today,” Wood says.

Wood leads the US portion of the Old Weather project, which originated in 2010 in the UK. Researchers have already added the weather observations from historic logbooks transcribed by Old Weather citizen scientists to international databases of climate data and used them in the model of the atmosphere that produced the new results.

Officers recorded the ship’s position at noon each day using a sextant. They would also note when they passed recognizable features, allowing researchers today to fully reconstruct the ship’s route to locate it in space and time.

While the historic sea ice observations have not yet been incorporated directly into the ice model, spot checks between the model and the early observations confirm the validity of the tool.

“This is independent verification that the model is doing the right thing,” Schweiger says.

The new, longer record provides more context for big storms or other unusual events and a new way to study the Arctic Ocean sea ice system.

“The observations that we have for sea ice thickness and variability are so limited,” Schweiger says. “I think people will start analyzing this record. There’s a host of questions that people can ask to help understand Arctic sea ice and predict is future.”

Scientists use the PIOMAS tool to monitor the current state of Arctic sea ice. The area of Arctic sea ice over the month of June 2019, and the PIOMAS-calculated volume, were the second-lowest for that time of year since the satellite record began.

The lowest-ever recorded Arctic sea ice area and volume occurred in September 2012. And while Schweiger believes the long-term trend will be downward, he’s not placing bets on this year setting a new record.

“The state of the sea ice right now is set up for new lows, but whether it will happen or not depends on the weather over the next two months,” Schweiger says.

The research appears in the Journal of Climate. Additional researchers from the University of Washington, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the National Archives contributed to the work. Funding came from the National Science Foundation, NASA, and the North Pacific Research Board.

Source: University of Washington