Two new studies highlight the problems with existing apps for students with special needs, their teachers, and their parents and work toward tools that do more to help children and the people who support them.

K-12 educators have been using technology in the classroom with increasing frequency but not always with great success, particularly when teaching students with special needs, says Gabriela Marcu.

That’s why Marcu, an assistant professor at the School of Information at the University of Michigan and an assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science at Michigan Engineering, has focused her research and technology design work on communication strategies that engage teachers, parents, and students in team-based solutions.

“We’re all more connected than ever, but in special education communication is still quite a challenge…”

Marcu believes technology, when well designed, can improve children’s behavioral outcomes and empower parents and teachers who are often strapped for time and resources.

“We’re all more connected than ever, but in special education communication is still quite a challenge,” Marcu says. “As a designer, I would like to shape the future of technology so we can make this better with the right tools.”

Getting on the same page

Making sure parents and educators are on the same page when it comes to behavioral intervention is critical to the success of students with special needs. And the mobile and social technologies we use every day could be the tools to get them there, Marcu says.

Parents must reinforce at home the work teachers do in the classroom, but that cannot happen without good communication, she says. Traditional methods like paper notes and even more contemporary forms of communication like email often don’t work.

Marcu and colleagues conducted research with teachers and parents of students receiving behavioral and mental health services to address autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorders, anxiety, trauma, and other needs.

By law, these students receive Individual Education Plans that require, among other things, documentation of progress toward goals stated in the plan. Yet, parents often don’t hear about the plan or outcomes because of these communication breakdowns.

The researchers talked with educators and parents in the United States and Sweden to find out how the communication normally occurred and attitudes about how well it was working.

Among the concerns:

- Parents have little face-to-face time with school practitioners and, therefore, limited opportunity to build a working relationship.

- Communications were not getting through, or when they did, parents said it often was too late for them to do something to address an issue.

- Educators were sometimes worried that if they shared information with parents about problem behaviors at school, this could lead to family conflict. This led to them curating what information they would share with parents.

- The communication usually only flowed one way, particularly when using paper-based methods. Parents and teachers both wanted two-way communication in order to ask one another questions and work together.

Marcu found some use of apps and websites to facilitate communication about Individual Education Plans, but overall she was surprised at how many existing tools don’t meet their needs. She is, therefore, designing new apps together with parents, educators, and children to improve their usability and usefulness.

More agency for students

For the second study, Marcu and colleagues developed and deployed a prototype to provide communication about expectations and consistent feedback to students with emotional or behavioral needs.

“The goal was to give children more agency over their success,” Marcu says.

The researchers conducted 30 months of fieldwork across four classrooms in both special education and regular education. Through 265 hours of observation, interviews, and focus groups, they explored the challenges educators faced implementing behavior management strategies.

Together with educators and psychologists, they came up with an idea for a classroom display that would give the students custom feedback about how they are doing toward their personal behavioral goals. They used human-centered design to develop a first prototype and see how its use affected a first grade classroom over 10 months of the school year.

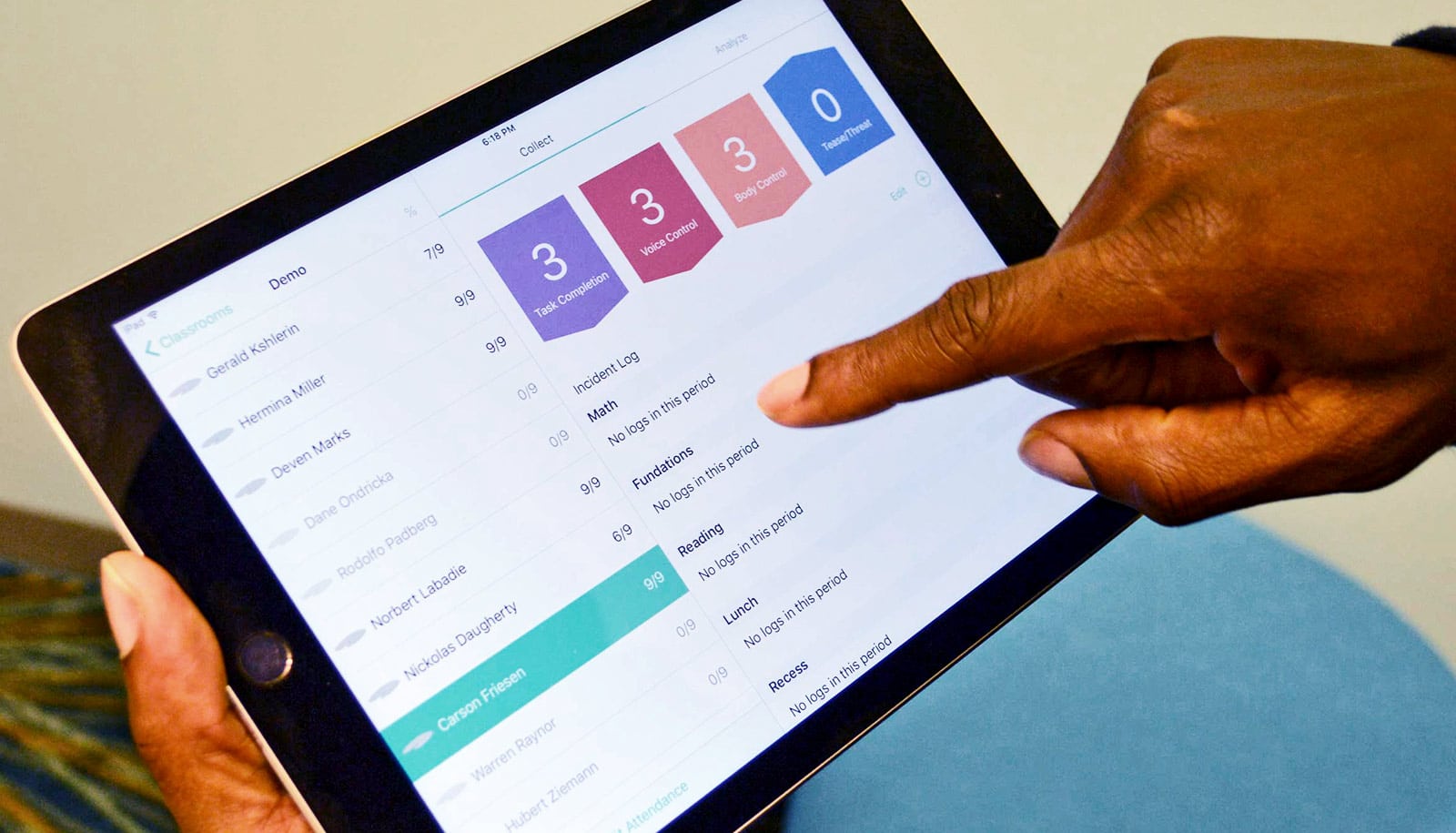

The teacher uses an iPad app to give students points for safe and appropriate behaviors, using categories that help students understand what physical, verbal, and social behaviors are expected of them. A display mounted on the wall at the front of the room shows a cartoon frog for each student in the class, each sitting on a lily pad. Each time the teacher logs a point using the iPad app, the student gets a notification through a frog in a pop-up message and sound effect.

Students trade their points in at the end of the day for a reward, and the program resets for the next collection cycle.

“We were definitely concerned about this backfiring, and that publicly displaying this type of information could lead to students feeling embarrassed or shaming one another about their behaviors. But that is where careful design comes in, by developing these technologies together,” Marcu says.

“What we found was that the display was so positive and encouraging that it actually led to students supporting one another to meet their goals.”

Marcu will share the first study at the CHI (human-computer interaction) conference and the second at the Pervasive Health Conference.

Source: University of Michigan