Classic antidepressants could help improve modern cancer treatments, according to a new study that shows they slowed the growth of pancreatic and colon cancers in mice.

When combined with immunotherapy, the antidepressants even stopped the cancer growth long-term. In some cases the tumors disappeared completely, researchers foybd. The findings will now be tested in human clinical trials.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter also known as the happiness hormone because of its beneficial effects on mood. In people with depression, the concentration of serotonin in the brain is reduced.

The hormone also influences many other functions throughout the body. The majority of the serotonin is not located in the brain, but stored in the blood platelets. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are used to treat depression, increase serotonin levels in the brain but decrease peripheral serotonin in platelets.

The involvement of serotonin in carcinogenesis was already known. Until now, however, the underlying mechanisms had remained obscure. Now, researchers have shown that SSRIs or other drugs that lower peripheral serotonin levels can also slow cancer growth in mice.

“Drugs that are already approved for clinical use as antidepressants could help improve treatment of hitherto incurable pancreatic and colorectal cancers,” says Pierre-Alain Clavien, director of the department of surgery and transplantation at the University of Zurich and University Hospital Zurich.

Although new, effective treatments—such as targeted antibodies or immunotherapies—have been available for several years, most patients with advanced-stage abdominal tumors such as colon or pancreatic cancer die within a few years of diagnosis.

One problem is that the tumor cells become resistant to the drugs over time and are no longer recognized by the immune system. Now, Clavien and colleague Anurag Gupta have discovered the role serotonin plays in this tumor cell resistance mechanism.

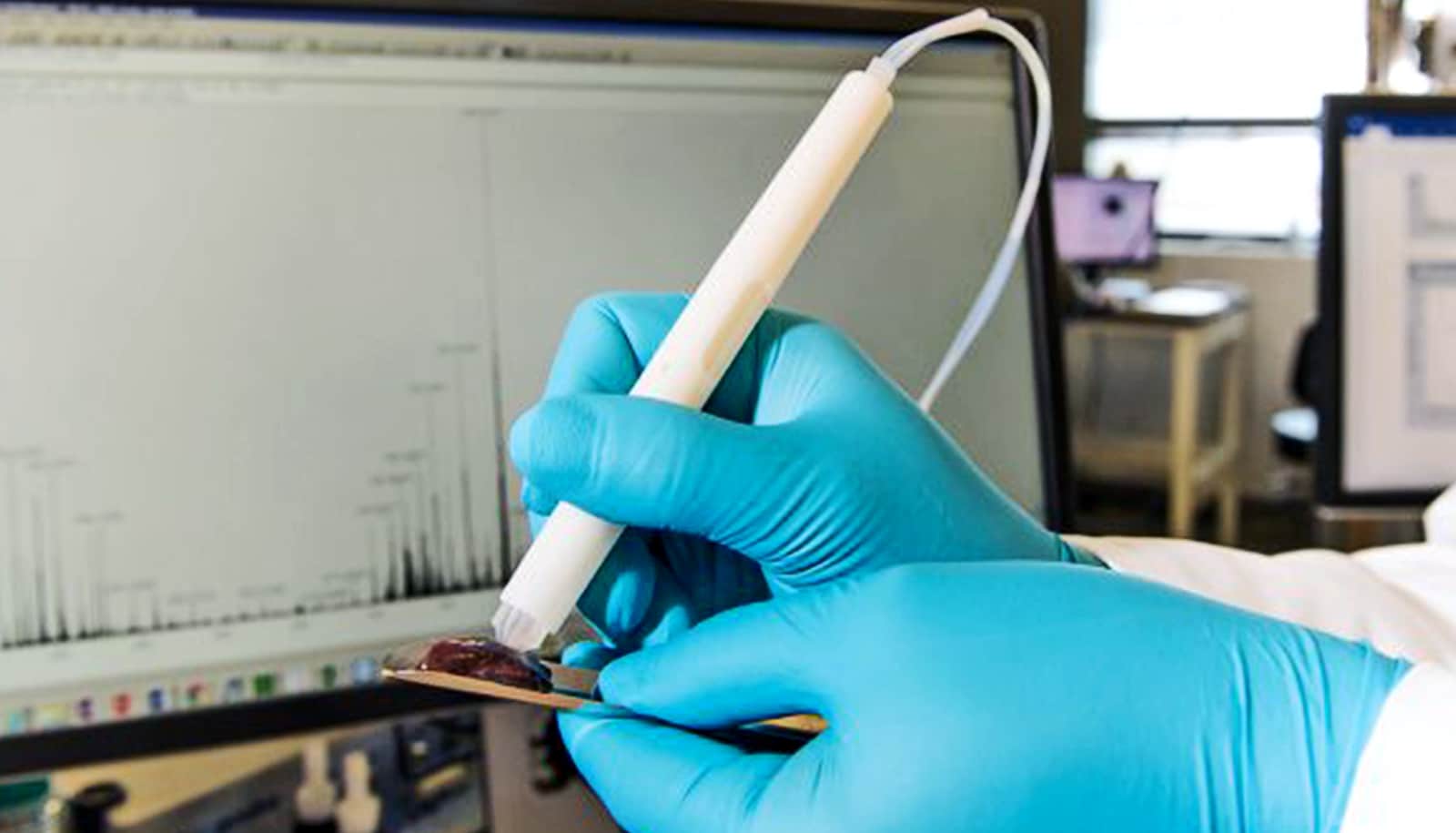

Cancer cells use serotonin to boost the production of a molecule that is immunoinhibitory, known as PD-L1. This molecule binds to killer T cells, a specific type of immune cell that recognizes and eliminates tumor cells, and renders them dysfunctional. The cancer cells thus avoid being destroyed by the immune system. In experiments with mice, the researchers showed that SSRIs or peripheral serotonin synthesis inhibitors prevent this mechanism.

“This class of antidepressants and other serotonin blockers cause immune cells to recognize and efficiently eliminate tumor cells again. This slowed the growth of colon and pancreatic cancers in the mice,” Clavien says.

PD-L1, via which serotonin exerts its effect, is also the target of modern immunotherapies, also called immune checkpoint inhibitors. In a next step, the researchers tested a dual treatment approach in mice: They combined immunotherapy, which increases the activity of killer T cells, with drugs that reduce peripheral serotonin.

The results were impressive: Cancer growth was suppressed in the animal models in the long term, and in some mice the tumors disappeared completely.

“Our results provide hope for cancer patients, as the drugs used are already approved for clinical use. Testing such drug combinations on cancer patients in clinical trials can be fast-forwarded due to the known safety and efficacy of the drugs,” Clavien says.

The study appears in Science Translational Medicine.

Source: University of Zurich