A new app would enable medical staff to take a picture of a patient’s inner eyelid with a smartphone to get an idea of whether they have anemia, researchers report.

A doctor can quickly get an idea of whether someone is anemic by pulling down the person’s eyelid and judging its redness, a color indicating the number of red blood cells.

But even a doctor’s eye isn’t precise enough to give a diagnosis without getting a blood sample from the patient.

The new software would instantly give doctors a near-accurate count of hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells. The team is working on embedding the software into a mobile app, which is in development.

The app could help bring sooner diagnoses and treatment or allow a person to better manage a blood disorder from home. The app also would help clinics in developing countries to better treat patients without the infrastructure to provide blood tests.

Quick and easy anemia app

Blood hemoglobin tests are regularly performed for a wide range of patient needs, from screenings for general health status to assessment of blood disorders and hemorrhage detection after a traumatic injury.

“This technology won’t replace a conventional blood test, but it gives a comparable hemoglobin count right away and is noninvasive and real-time,” says Young Kim, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at Purdue University. “Depending on the hospital setting, it can take a few hours to get results from a blood test. Some situations also may require multiple blood tests, which lead to more blood loss.”

The method is a portable version of a commonly-used technique, called spectroscopic analysis, that detects hemoglobin by the specific way that it absorbs visible light. The resulting spectrum of light signals accurately gives a measure of blood hemoglobin content.

Kim’s team developed an algorithm that uses an approach known as super-resolution spectroscopy to convert low-resolution smartphone photos to high-resolution digital spectral signals. Another computational algorithm detects these signals and uses them to quantify blood hemoglobin content.

“The idea is to get a spectrum of colors using a simple photo. Even if we had several photos with very similar redness, we can’t clearly see the difference. A spectrum gives us multiple data points, which increases chances of finding meaningful information highly correlated to blood hemoglobin level,” says Sang Mok Park, a PhD candidate in biomedical engineering.

Compared to a spectroscopic analysis, the smartphone app wouldn’t require any extra hardware to detect and measure hemoglobin levels.

153 eyelids

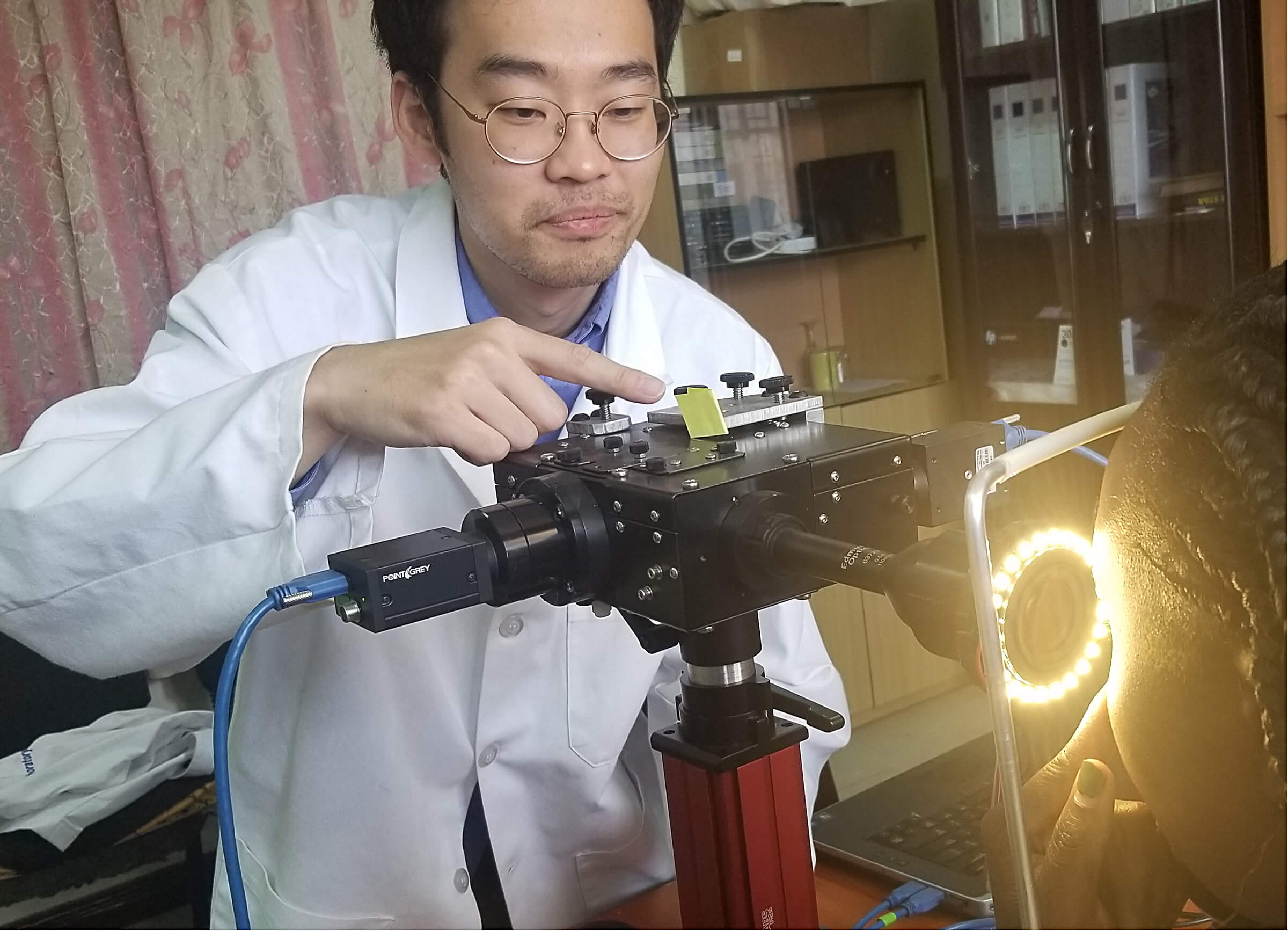

The team created this tool based on data from a study of 153 patients referred for conventional blood tests at the Moi University Teaching and Referral Hospital in Kenya. Kim’s team began conducting this study in 2018 in collaboration with the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare program.

As each patient took a blood test, a researcher took a picture of the patient’s inner eyelid with a smartphone. Kim’s team used this data to train the spectral super-resolution algorithm to extract information from smartphone photos.

Using results from the blood tests as a benchmark, the team found that the software could provide comparable measurements for a wide range of blood hemoglobin values.

The app in development includes several features designed to stabilize smartphone image quality and synchronize the smartphone flashlight to obtain consistent images. It also provides eyelid-shaped guidelines on the screen to ensure that users maintain a consistent distance between the smartphone camera and the patient’s eyelid.

“The app also wouldn’t be thrown off by skin color. This means that we can easily get robust results without any personal calibrations,” Park says.

In a separate clinical study, the team is using the app to assess blood hemoglobin levels of cancer patients at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center. The researchers also are working with the Shrimad Rajchandra Hospital to develop a better algorithm for hospitals and frontline healthcare workers in India.

A paper on the software appears in Optica. The Purdue Research Foundation Office of Technology Commercialization has filed patent applications for this technology. The researchers are looking for partnerships to further develop the smartphone app.

Support for the work came from the National Institutes of Health, the US Agency for International Development, and the Purdue Shah Family Global Innovation Lab.

Source: Purdue University