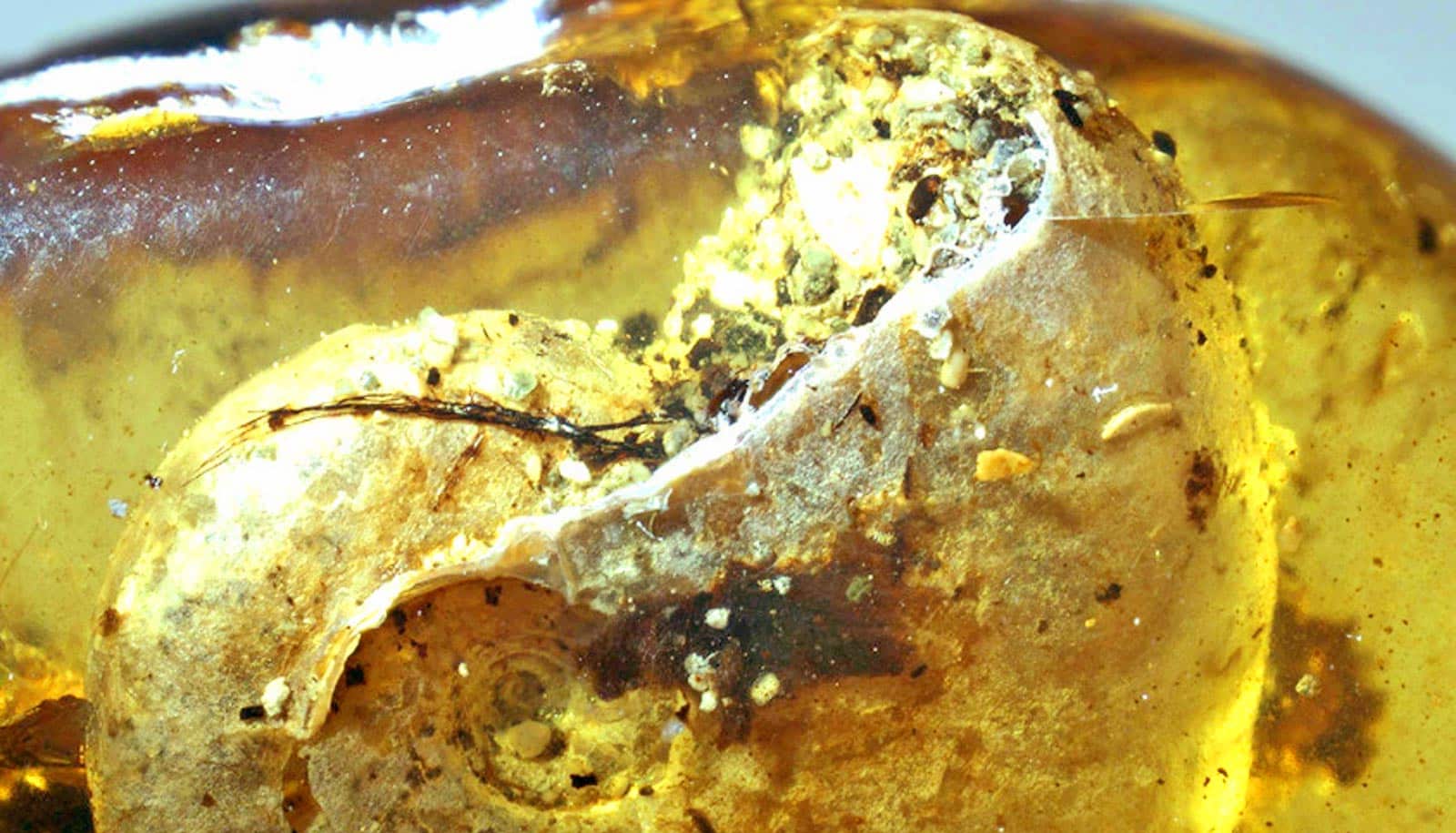

The discovery of a 100-million-year-old ammonite—a distant relative of modern squid and octopuses—in amber is significant and surprising, researchers say.

Scientists say the lump of fossilized tree resin, from the mines of northern Myanmar, sheds light on ancient sea life.

The fossil is surprising, researchers say, because amber forms on land from resin-producing plants, so it is rare to find marine life entombed in the substance.

“The excitement of the discovery is its potential to open the window on past life,” says David Dilcher, professor emeritus of biology at Indiana University. “The preservation of amber from an age as old as this, it helps increase our understanding of ancient life and the world in which ancient life lived.”

Ammonites were shelled mollusks that lived on Earth during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods—the same time as some dinosaurs. Typically fossilized as impressions in shale, ammonites’ preservation in amber provides a unique 3D look at the ancient sea creatures, Dilcher says.

In addition to trapping the shell of an ammonite, the amber also contains the fossils of at least 40 other organisms from both land and sea habitats, such as spiders, snails, and wasps. This diversity of organisms preserved in one place may one day have the most potential for future research, Dilcher says.

Possible theories for how land and sea organisms ended up trapped together include a coastal forest with resin-producing trees growing close to marine debris on the edge of a beach, a tsunami that flooded an amber-producing forest with marine debris, or tropical storms that blew marine debris inland, Dilcher says.

However, the first theory seems most likely, the scientists posit. The lack of soft tissue from the ammonite and other marine organisms preserved in the amber suggests they were dead long before their shells encountered the ancient tree resin.

This makes the tsunami theory less likely, and the rarity of the presence of marine organisms in other amber specimens found to date suggests the tropical storms wouldn’t have been frequent occurrences.

The study appears in PNAS.

Source: Indiana University