Calling out discriminatory behavior is an effective way for white students to help combat racism against Black and Latino science, technology, engineering, and math students, researchers report.

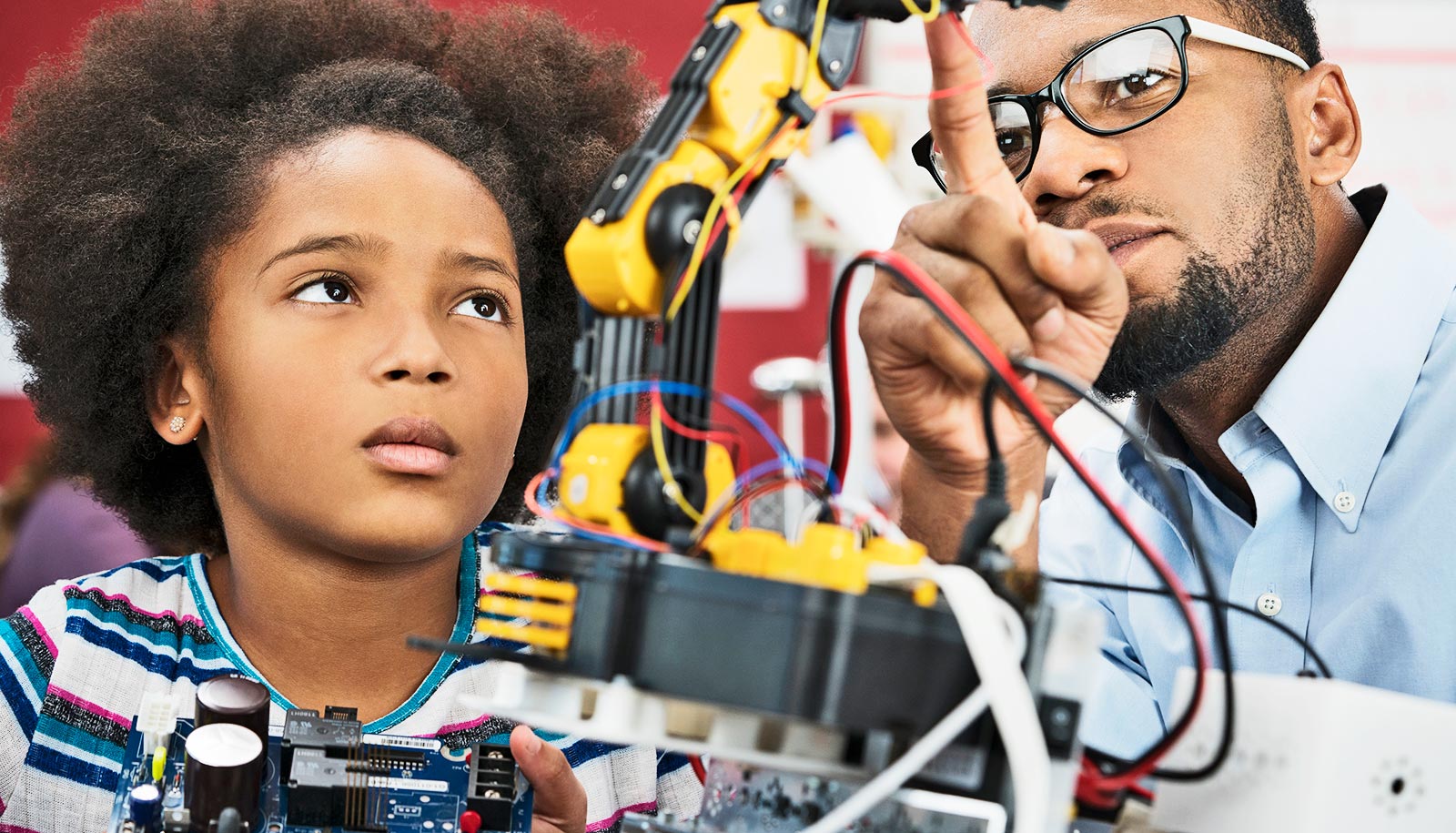

The new research, led by Eden King and Mikki Hebl from Rice University, examines whether Black and Latino college students face discrimination when studying science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) and how allies can help combat racist behavior in these situations.

“There is already a serious lack of representation of minorities in STEM, and we know from prior research on this topic that supportive environments are critical to people excelling in and pursuing careers within this field,” says King, a professor of psychological sciences. “In this research, we really wanted to pinpoint how subtle discrimination is affecting minorities in STEM and how other students can provide allyship.”

The research was conducted in four parts across multiple higher education institutions. In the first study, 125 Black, Hispanic, and multiracial students were surveyed about discriminatory behavior in STEM classrooms over a three-week period. Any time they felt “off” about an encounter, they were encouraged to fill out a survey.

“We wanted to understand as much about the students’ experiences as possible,” King says. “We encouraged the survey respondents to indicate when their experiences were even a little awkward, weird, or negative in any way. Maybe some of these experiences were related to their race or ethnicity and maybe not. Maybe a classmate made an insensitive comment in class. Maybe a professor ignored their raised hand or they couldn’t find a study partner. And so on.”

According to surveys immediately following these negative events, students said that they experienced such situations in about 20% of their STEM classes. They also noted that bystanders were unlikely to intervene on their behalf.

In the second study, researchers surveyed 70 white students who overwhelmingly acknowledged that the events reported by Black and Latino students in STEM educational settings were problematic. However, the majority of these individuals did not feel compelled to intervene.

“When interviewing these students, they noted that they felt like it was not appropriate or ‘not their place’ to say something,” says Hebl, chair of psychological sciences. “These results provide insight into the lack of bystander intervention in the first study, suggesting this was not motivated by any negative intent, but rather people just didn’t perceive that it was their responsibility.”

In the third and fourth parts of the study, the researchers worked with more than 200 participants of different races via Zoom in two separate scenarios. The goal was to determine the effectiveness of encouraging personal responsibility to fight prejudice and engage in allyship. Two sets of actors planted in the experiment 1.) simulated discriminatory behavior, and 2.) were the targets of such behavior, with the goal of examining the reaction of a third set of individuals, the bystander participants.

The third study revealed that enhancing a bystander’s sense of psychological standing—that is, their feeling of legitimacy to perform an action with respect to a cause or an issue—increased the likelihood they would confront prejudice.

“In the third study, the person being targeted made a comment that, ‘We are all [university name] students, what do y’all think about that?’ This statement encouraged individuals to speak up,” King says.

The fourth and final study extended this phenomenon. When fellow bystanders (not just targets) appealed to others to call out discriminatory behavior, they were more likely to do so.

“The main takeaway from the research is this: Allyship is just critical when it comes to combating prejudice,” Hebl says. “We need more allies for marginalized individuals in all walks of life, and definitely in STEM fields.”

The researchers say they hope future research will address more ways to get allies to assume psychological standing and to call out discriminatory behavior when they see it happening to others, particularly those who may be vulnerable to reporting it themselves.

The study appears in the Journal of Business and Psychology.

Source: Rice University