This Veterans Day, the parades and memorials should remind all of us that ultra-nationalism—surging anew in Europe, the US, and South America—harbors the spark to ignite another catastrophic international conflict, historian Matthew Stanley argues.

“I would say we are pretty far down that road again,” warns Stanley, a professor in New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, historian of science, and the author of Einstein’s War (Penguin Random House, 2019).

This year, Veterans Day, the federal holiday honoring the service and sacrifice of US military vets, takes place on November 11, coinciding with Europe’s Armistice or Remembrance Day, which commemorates the end of World War I. The observances hold added poignancy on both sides of the Atlantic this year, as they fall during the 100th year since the formal signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the agreement that consigned the Great War to history.

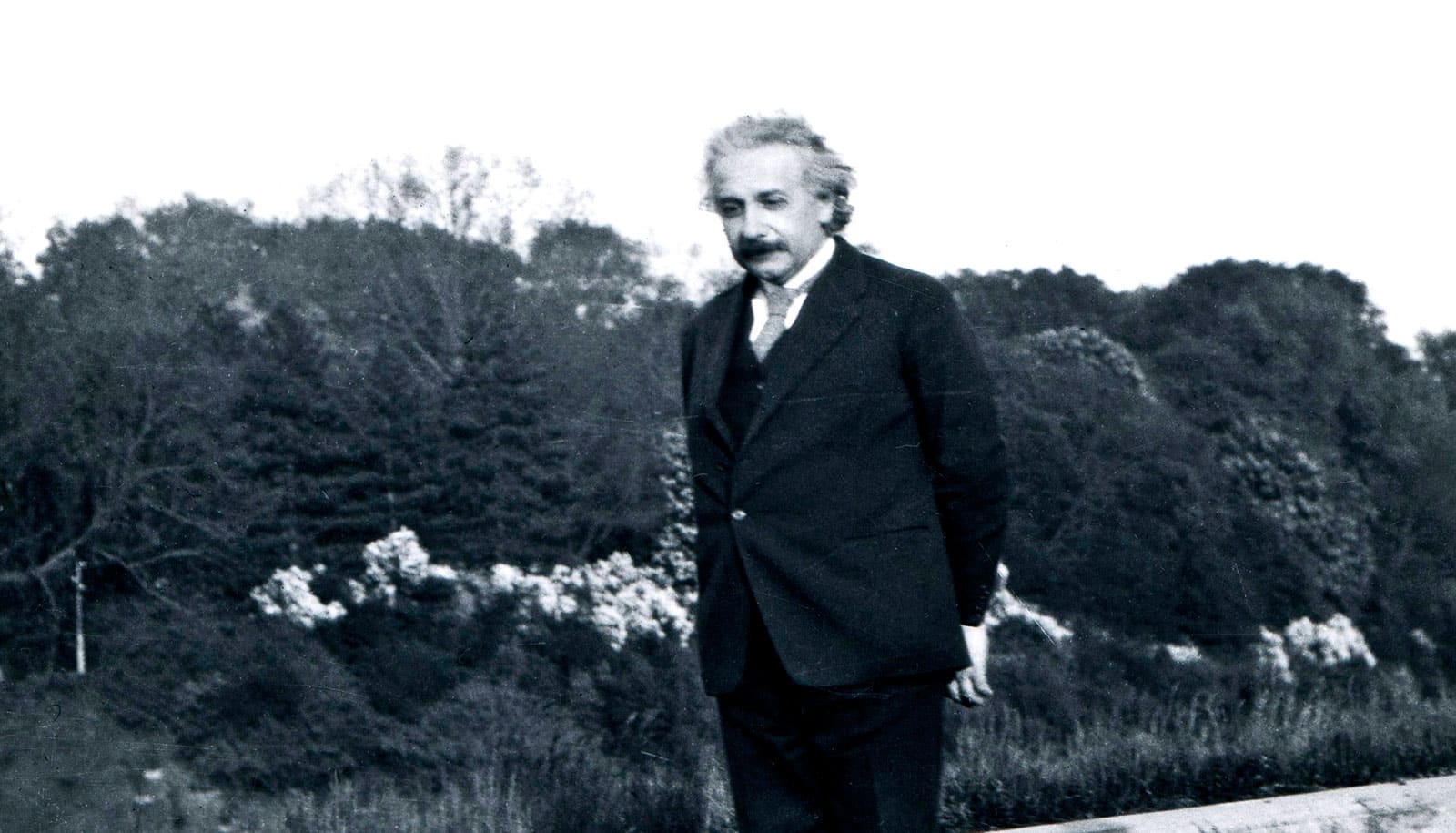

Stanley’s new book documents how Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity—published in 1915 while he was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics in Berlin—was met with great curiosity but little engagement by peer scientists from Allied nations fighting one of the deadliest wars in history against Germany and other Central Powers.

Fortunately, Sir Arthur Eddington, an English astronomer and secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society, was a pacifist like Einstein and chose to look past the scientist’s home country to pursue scientific truth. As one of the few astronomers with the mathematical skills to understand general relativity, Eddington went on to prove the theory’s validity in an experiment he conducted off the coast of West Africa during a solar eclipse in May 1919.

It was a triumph, however rare for that time, or really any time, over scientific nationalism, Stanley says. Here, he explains what lessons from that story we can apply within our own political environment:

My sense is that science typically gets a pass in discussions of nationalism.

Yes—generally we think of science as transnational and purely intellectual, not bound up with questions of patriotism. But science is always tied up with political questions, especially in wartime. Its most distinctive feature is the creation of a sort of us-vs.-them mentality, and marking out “the enemy” with a broad brush.

What did scientific nationalism look like a century ago?

During WWI, you had the British scientists saying, “What we are doing is real science, whereas German science is untrustworthy.” You had German scientists who declared that they would no longer cite any English scientific papers, and there were British scientists who says they were not going to allow the use of the German language at scientific conferences anymore.

They refused to send scientific journals back and forth, and scientists who traveled to study in the other country were arrested as spies. It was really quite remarkable. Strong arguments were made on both sides that the practice of science could not possibly be international and was very much a racial thing based in each individual country.

What about Einstein? What was his take on nationalism in the realm of science?

Oh, he strongly opposed it. He called it “swine mind”—that is, thinking like a member of a herd of pigs. And he thought that scientists should be against all forms of nationalism.

After World War I, did science return to an international footing once and for all?

In fact, it didn’t. During WWII you had countries fiercely guarding their scientific information, fearing that it could be weaponized. In the Cold War period, the whole space race became an important part of nationalist propaganda, and the United States, for instance, built huge particle accelerators to show that American science was superior to that of the Russians, and denied passports to Soviet scientists who wanted to visit America.

The US government was explicit that science was a tool of diplomacy and soft power to exert American influence. And today the issue of whether or not US scientists have ties to Iran and China—including those working on basic biochemical research—remains a big thing. Scientists have lost their jobs because they’ve worked too closely with these other countries. It’s pure nationalism at work.

You point out that one of Einstein’s friends, the German scientist Fritz Haber, invented chemical weapons that were used in WWI to horrible effect. Is it fair to say that modern warfare, and nationalism, feeds off of scientific advances?

Nationalism is a complicated thing. We know that the Treaty of Versailles ultimately gave rise to WWII because of the punitive terms it imposed on Germany. And during World War II, Einstein and other scientists who had fled Europe shared a common fear of fascism.

Seeing fascism and Nazism as an existential threat, Einstein came to famously recommend the building of the atomic bomb, after having complained throughout the First World War about how scientists were being co-opted. He sacrificed his own ideals hoping to stop the Nazis, only to become a renewed pacifist after Hiroshima.

It seems that the pull of politics during wartime can be too strong even for great scientific minds to resist.

Science as a community did not rise above nationalism during WWI, but there were individuals—like Einstein—who ended up doing a tremendous amount of good and overcoming a lot of boundaries. It was certainly Einstein’s view that human beings’ natural state was tribalistic and nationalistic, but that we certainly could work hard to overcome it.

In the end, people need to be willing to put their ideals and views on the line in difficult circumstances. If that doesn’t happen, then everything—in spite of the Constitution and in spite of the courts—just slides away.

Source: NYU