Thanks to one peculiar characteristic of carbon nanotubes, engineers will soon be able to measure the accumulated strain in an airplane, a bridge, or a pipeline—or just about anything—over the entire surface or down to microscopic levels, according to new research.

They’ll do so by shining a light onto structures coated with a two-layer nanotube film and protective polymer. Strain in the surface will show up as changes in the wavelengths of near-infrared light emitted from the film that a miniaturized hand-held reader captures.

The results will show engineers and maintenance crews whether structures like bridges or aircraft have been deformed by stress-inducing events or regular wear and tear.

Like a white shirt under an ultraviolet light, single-wall carbon nanotubes fluoresce, a property discovered in 2002 in the lab of chemist Bruce Weisman. In a basic research project a few years later, the group showed that stretching a nanotube changes the color of its fluorescence.

When Weisman’s results came to the attention of civil and environmental engineer Satish Nagarajaiah—who had been working independently on similar ideas using Raman spectroscopy, but at the macro scale, since 2003—he suggested collaborating to turn that scientific phenomenon into a useful technology for strain sensing.

Color changing

Now, Nagarajaiah and Weisman have published a pair of papers about their “smart skin” project. The first appears in Structural Control & Health Monitoring, and introduces the latest iteration of the technology they first revealed in 2012.

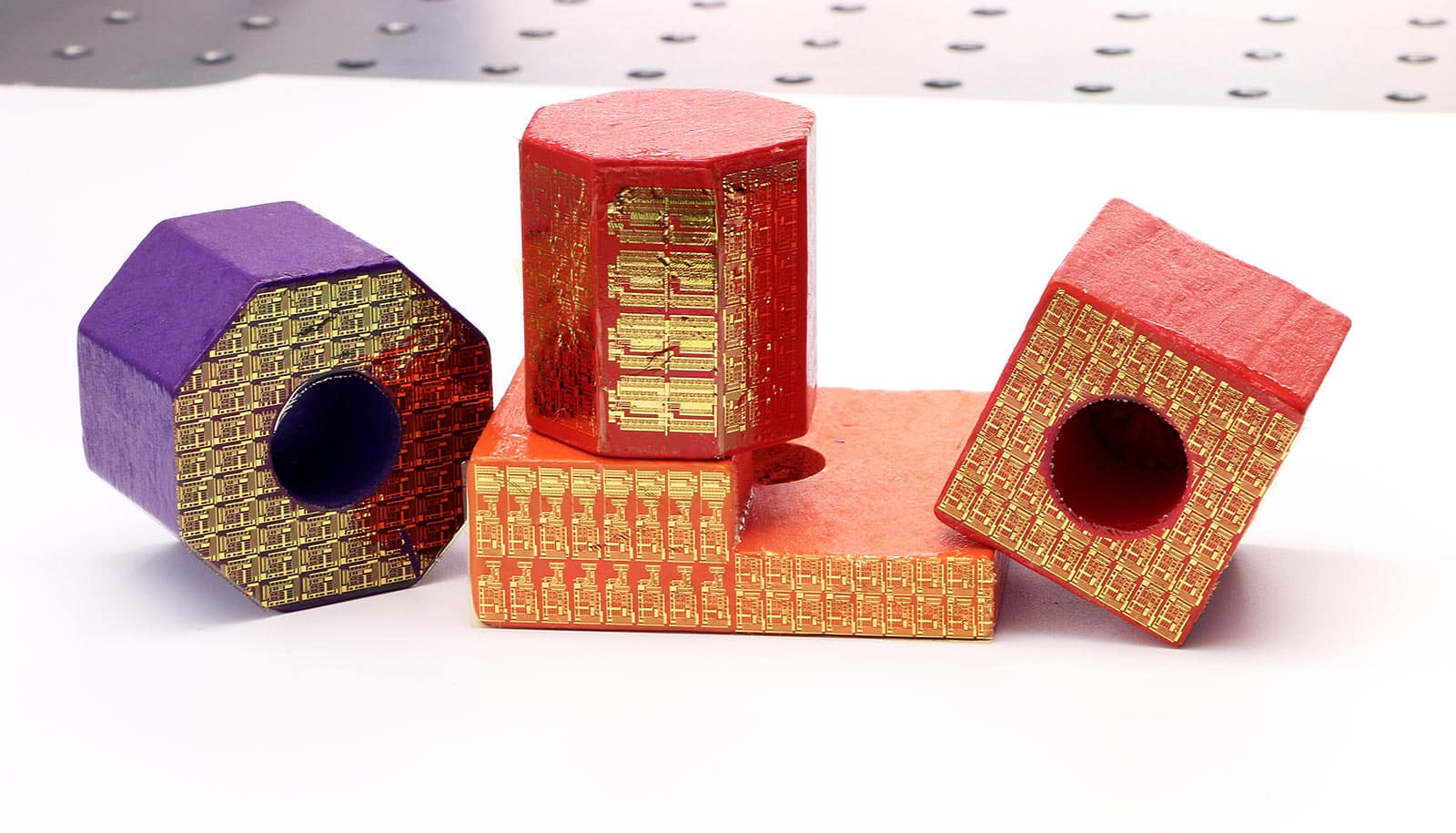

It describes a method of depositing the microscopic nanotube-sensing film separately from a protective top layer. Color changes in the nanotube emission indicate the amount of strain in the underlying structure. The researchers say it enables two-dimensional mapping of accumulated strain that no other non-contact method can achieve.

The second paper, which appears in the Journal of Structural Engineering, details the results of testing smart skin on metal specimens with irregularities where stress and strain are often concentrated.

The two-layer film is only a few microns thick, a fraction of the width of a human hair, and barely visible on a transparent surface.

“The project started out as pure science about nanotube spectroscopy, and led to the proof-of-principle collaborative work that showed we could measure the strain of the underlying substrate by checking the spectrum of the film in one place,” says Weisman, a professor of chemistry and of materials science and nanoengineering at Rice University. “That suggested the method could be expanded to measure whole surfaces. What we’ve shown now is a lot closer to that practical application.”

Since the initial report, the researchers have refined the composition and preparation of the film and its airbrush-style application, and also developed scanner devices that automatically capture data from multiple programmed points. Unlike conventional sensors that only measure strain at one point along one axis, researchers can selectively probe the smart film to reveal strain in any direction and location.

The two-layer film is only a few microns thick, a fraction of the width of a human hair, and barely visible on a transparent surface.

“In our initial films, the nanotube sensors were mixed into the polymer,” says Nagarajaiah, a professor of civil and environmental engineering, of mechanical engineering, and of materials science and nanoengineering. “Now that we’ve separated the sensing and the protective layers, the nanotube emission is clearer and we can scan at a much higher resolution. That lets us capture significant amounts of data rather quickly.”

‘Points of failure’

The researchers tested smart skin on aluminum bars under tension with either a hole or a notch to represent the places where strain tends to build. Measuring these potential weak spots in their unstressed state and then again after applying stress showed dramatic changes in strain patterns pieced together from point-by-point surface mapping.

“We know where the high-stress regions of the structure are, the potential points of failure,” Nagarajaiah says. “We can coat those regions with the film and scan them in the healthy state, and then after an event like an earthquake, go back and re-scan to see whether the strain distribution has changed and the structure is at risk.”

“We measured points 1 millimeter apart, but we can go 20 times smaller when necessary without sacrificing strain sensitivity…”

In their tests, the researchers say the measured results were a close match to strain patterns obtained through advanced computational simulations. Readings from the smart skin allowed them to quickly spot distinctive patterns near the high-stress regions, Nagarajaiah says. They were also able to see clear boundaries between regions of tensile and compressive strain.

“We measured points 1 millimeter apart, but we can go 20 times smaller when necessary without sacrificing strain sensitivity,” Weisman says. That’s a leap over standard strain sensors, which only provide readings averaged over several millimeters, he says.

The researchers see their technology making initial inroads in niche applications, like testing turbines in jet engines or structural elements in their development stages. “It’s not going to replace all existing technologies for strain measurement right away,” Weisman says. “Technologies tend to be very entrenched and have a lot of inertia.

“But it has advantages that will prove useful when other methods can’t do the job,” he says. “I expect it will find use in engineering research applications, and in the design and testing of structures before they are deployed in the field.”

With their smart skin refined, the researchers are working toward developing the next generation of the strain reader, a camera-like device that can capture strain patterns over a large surface all at once.

The Office of Naval Research and the Welch Foundation supported the research.

Source: Rice University