Microscopic particles in air pollution that pregnant women inhale may damage fetal cardiovascular development, according to a new study with mice.

Researchers found that early in the first trimester and late in the third trimester were critical windows during which pollutants most affect the mother’s and fetus’ cardiovascular systems.

“These findings suggest that pregnant women, women of child-bearing years who may be pregnant, and those undergoing fertility treatments should avoid areas known for high air pollution or stay inside on high-smog days to reduce their exposure,” says Phoebe Stapleton, an assistant professor at the Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy and faculty member at the Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute at Rutgers University. “Pregnant women should also consider monitoring their indoor air quality.”

What a mother inhales affects her circulatory system, which is constantly adapting to supply adequate blood flow to the fetus as it grows. Exposure to these pollutants can constrict blood vessels, restricting blood flow to the uterus and depriving the fetus of oxygen and nutrients, which can result in delayed growth and development. It can also lead to common pregnancy complications, such as intrauterine growth restriction.

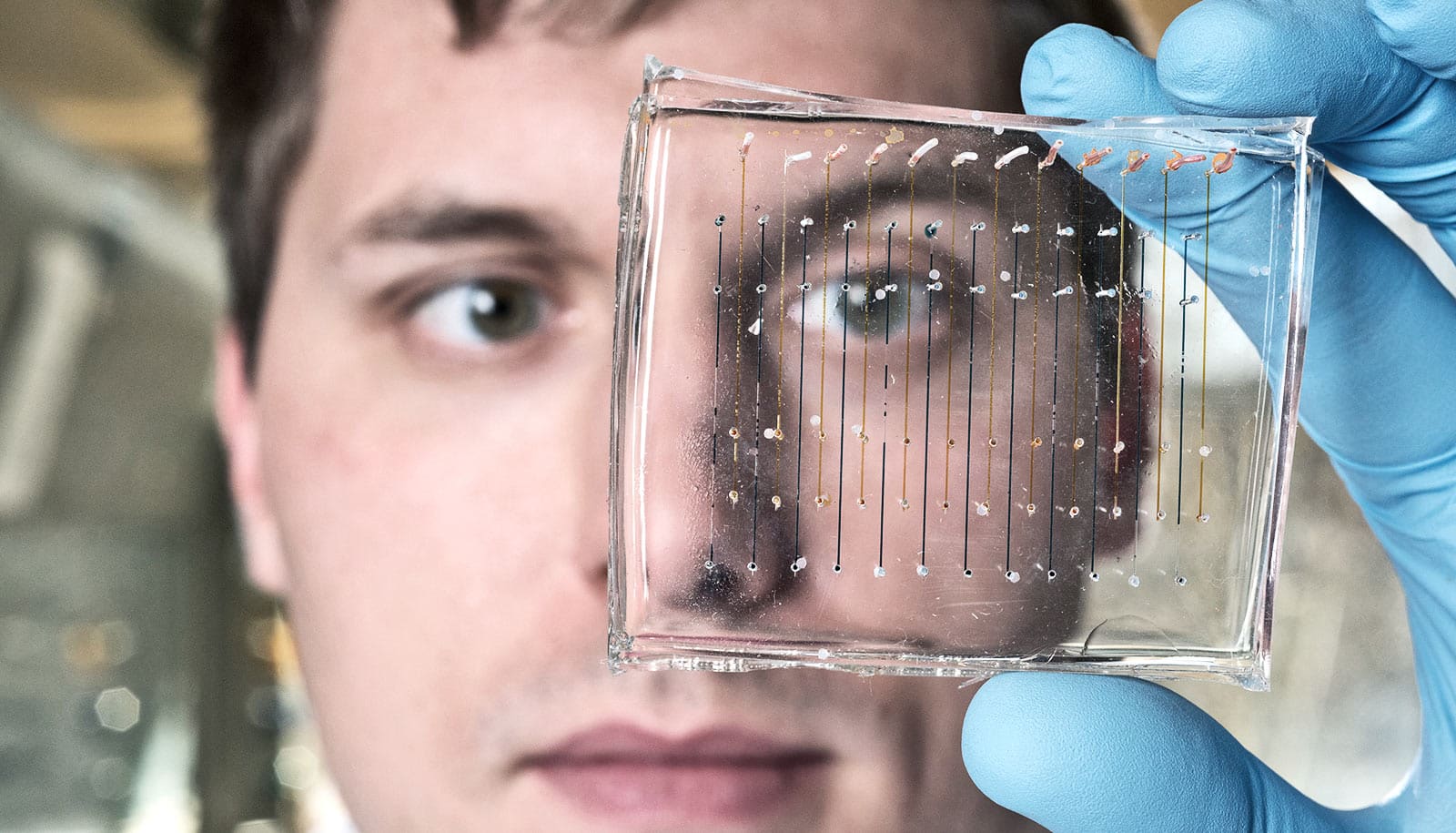

The researchers looked at how a single exposure to nanosized titanium dioxide aerosols—a surrogate for particles found in typical air pollution affected the circulatory systems of pregnant rats and their fetuses during their first, second, and third trimesters. The researchers compared the results to pregnant rats that they exposed only to high-efficiency filtered air.

The researchers found that exposures to pollutants early in gestation significantly impact a fetus’s circulatory system, specifically the main artery and the umbilical vein. Later exposure had the most impact on fetal size since the restricted blood flow from the mother deprives the fetus of nutrients in this final stage.

In non-pregnant animals, past research has linked even a single exposure to these nanoparticles to impaired function of the arteries in the uterus. The new study finds that one exposure late in pregnancy can restrict maternal and fetal blood flow, which can continue to affect the child into adulthood.

“Although nanotechnology has led to achievements in areas such as vehicle fuel efficiency and renewable energy, not much is known about how these particles affect people at all stages of development,” says Stapleton.

By 2025, experts project the annual global production of nanosize titanium dioxide particles to reach 2.5 million metric tons. Besides representing the very small particles found in air pollution, titanium dioxide also is commonly used in many personal care products including sunscreens and face powders.

The study appears in the journal Cardiovascular Toxicology.

Source: Rutgers University