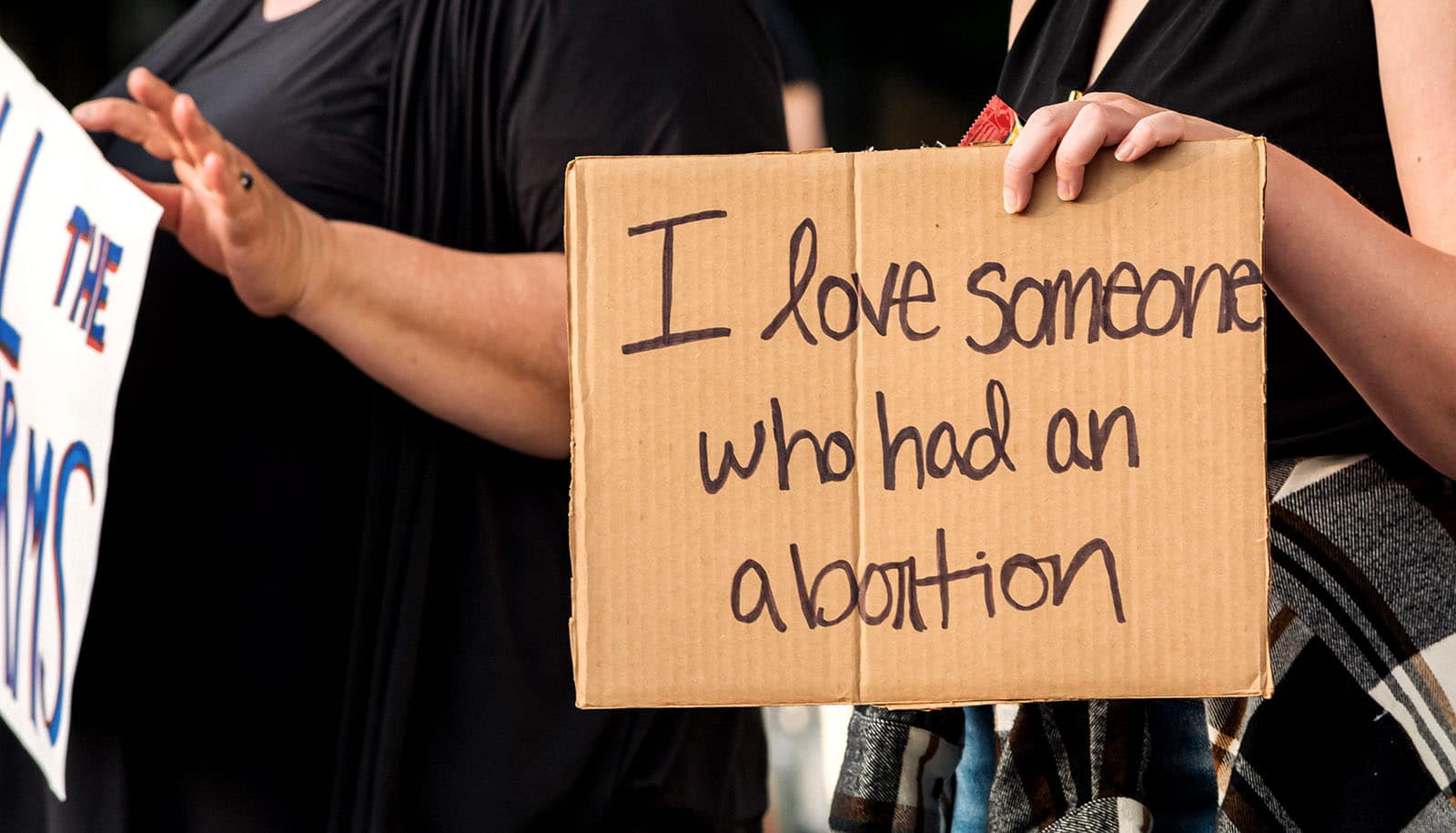

New research offers ideas for making people more willing to disclose abortion on surveys.

Even before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, many people taking surveys didn’t report their abortion experiences, a phenomenon that has long compromised research on abortion and a range of related topics.

A new study in the journal Culture, Health & Sexuality suggests several strategies that may reduce stigma, increase reporting, and improve research that relies upon it.

“In earlier work, we showed that fewer than half of women report abortions in surveys, which creates a huge challenge for our ability to study abortion,” says Laura Lindberg, a professor at the Rutgers School of Public Health and lead author of the study.

“It’s not just that we’re missing so many cases but that we’re missing them in a biased way. Without good measures of abortions, we don’t have good measures of pregnancy experiences overall. Efforts to improve abortion reporting are needed to strengthen the quality of pregnancy data to support maternal, child, and reproductive health.”

With funding from the National Institutes of Health, Lindberg and colleagues from the Guttmacher Institute in New York developed a variety of potential survey questions that approached abortion in different ways, each designed to minimize stigma, intrusiveness, and confusion. Team members then asked 64 racially and ethnically diverse cisgender women ages 18 to 49 which potential question sets seemed most likely or least likely to inspire disclosure.

Analysis of their responses suggested a few strategies for improved reporting, such as:

- Including abortion as part of a list of other sexual and reproductive health services

- Asking a yes or no question about lifetime experience of abortion instead of asking about the number of abortions

- Developing an improved introduction to abortion-related questions

The study team used these insights to design a larger follow-up that could change the abortion question designs used in surveys by National Center for Health Statistics and researchers worldwide. A follow-up study randomly divided 6,000 women into six groups of 1,000 and surveyed each group about abortion history with different question sets. If the published paper shows that any experimental question set produced more disclosure than the existing CDC survey language (given to one group to act as a control), the question set that maximized disclosure likely will become the new standard.

“I have a long-standing relationship with staff at the National Center for Health Statistics, and I’ve been in communication with them since before this project even started and presented ongoing findings there,” Lindberg says. “So, there’s definitely an opportunity to influence how national surveys are written as well as provide guidance to the field.”

There is a wild card that may alter willingness to report an abortion—and, therefore, the most effective way to ask about it: The US Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, which says that abortion isn’t a constitutionally protected right and has allowed states to enact abortion bans.

“If it was hard to measure abortion before, it’s going to be even more challenging moving forward,” Lindberg says. “We’re going from asking women to report an activity that, while sensitive and stigmatized, was at least legal to asking them to report an activity that may be actually illegal in some places and may be widely perceived as illegal in places where it isn’t.”

Still, Lindberg says improving abortion measurement and survey quality is crucial to help monitor and understand the impact of new abortion laws.

Source: Rutgers University