A new, air-powered computer sets off alarms when certain medical devices fail.

The invention is a more reliable and lower-cost way to help prevent blood clots and strokes—all without electronic sensors.

Described in a paper in the journal Device, the computer not only runs on air, but also uses air to issue warnings. It immediately blows a whistle when it detects a problem with the lifesaving compression machine it is designed to monitor.

Intermittent pneumatic compression or IPC devices are leg sleeves that fill with air periodically and squeeze a person’s legs to increase blood flow. This prevents clots that lead to blocked blood vessels, strokes, or death. Typically, these machines are powered and monitored by electronics.

“IPC devices can save lives, but all the electronics in them make them expensive. So, we wanted to develop a pneumatic device that gets rid of some of the electronics, to make these devices cheaper and safer,” says William Grover, associate professor of bioengineering at the University of California, Riverside and corresponding paper author.

Pneumatics move compressed air from place to place. Emergency brakes on freight trains operate this way, as do bicycle pumps, tire pressure gauges, respirators, and IPC devices. It made sense to Grover and his colleagues to use one pneumatic logic device to control another and make it safer.

This type of device operates in a similar way to electronic circuits, by making parity bit calculations.

“Let’s say I want to send a message in ones and zeroes, like 1-0-1, three bits,” Grover says. “Decades ago, people realized they could send these three bits with one additional piece of information to make sure the recipient got the right message.”

That extra piece of information is called a parity bit. The bit is a number—1 if the message contains an odd number of ones, and 0 if the message contains an even number of ones. Should the number one appear at the end of a message with an even number of bits, then it is clear the message was flawed. Many electronic computers send messages this way.

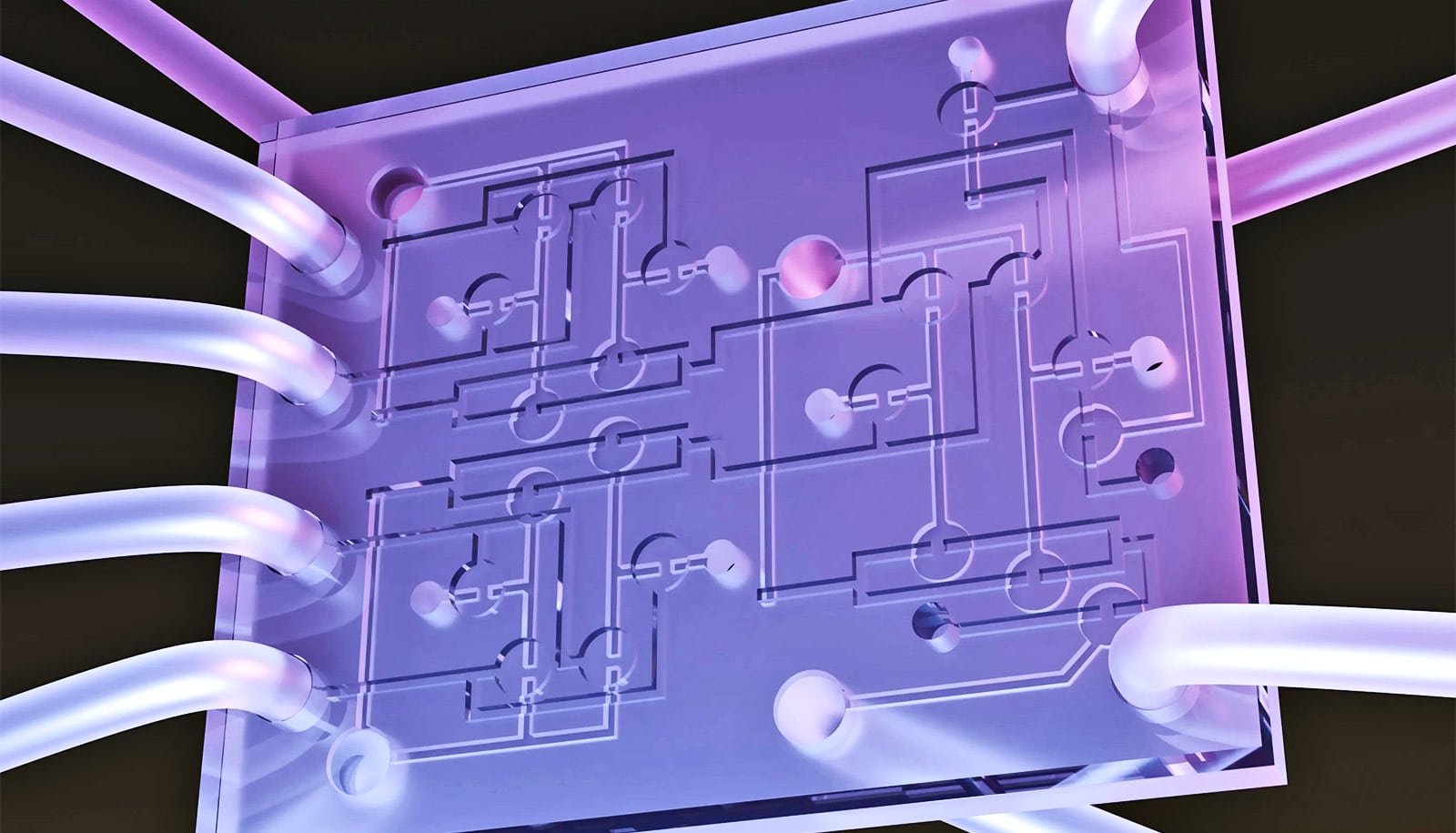

An air-powered computer uses differences in air pressure flowing through 21 tiny valves to count the number of ones and zeroes. If no error in counting has occurred, then the whistle doesn’t blow.

If it does blow, that’s a sign the machine requires repairs. Grover and his students, in a video demonstrating the air computer, are shown damaging an IPC device with a knife, rendering it unusable. Seconds later, the whistle blows.

“This device is about the size of a box of matches. It replaces a handful of sensors as well as a computer,” Grover says. “So, we can reduce costs while still detecting problems in a device. And it could also be used in high humidity or high temperature environments that aren’t ideal for electronics.”

The IPC device monitoring is only one application for air computing. For his next project, Grover would like to design a device that could eliminate the need for a job that kills people every year: moving around grain at the top of tall silos.

Tall buildings full of corn or wheat, grain silos are a common sight in the Midwest. Often times, a human has to go inside with a shovel to break up the grains and even out the piles inside.

“A remarkable number of deaths occur because the grain shifts and the person gets trapped. A robot could do this job instead of a person. However, these silos are explosive, and a single electric spark could blow a silo apart, so an electronic robot may not be the best choice,” Grover says.

“I want to make an air-powered robot that could work in this explosive environment, not generate any sparks, and take humans out of danger.”

Air-powered computing is an idea that has been around for at least a century. People used to make air-powered pianos that could play music from punched rolls of paper. After the rise of modern computing, engineers lost interest in pneumatic circuits.

“Once a new technology becomes dominant, we lose awareness of other solutions to problems,” Grover says. “One thing I like about this research is that it can show the world that there are situations today when 100-plus-year-old ideas can still be useful.”

Source: UC Riverside