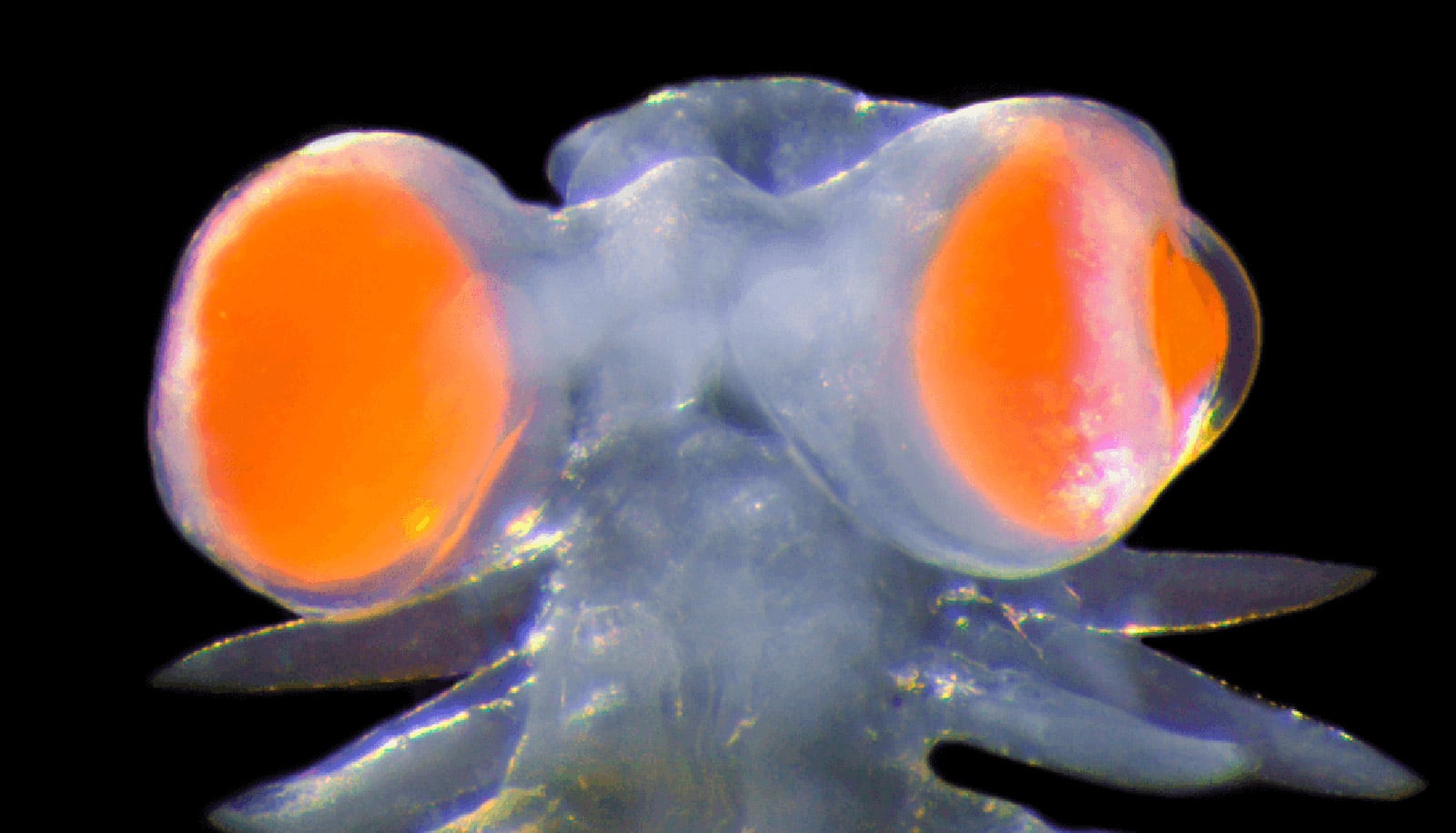

New research digs into the mysteries behind the huge eyes of the Vanadis bristle worm.

The worm’s eyes weigh about twenty times as much as the rest of the animal’s head and seem grotesquely out of place on this tiny and transparent marine critter.

It’s as if two giant, shiny red balloons have been strapped to its body. Indeed, if our eyes were proportionally as big as the ones of this Mediterranean marine worm, we would need a big sturdy wheelbarrow and brawny arms to lug around the extra 100 kg (220 pounds).

Vanadis bristle worms, also known as polychaetes, can be found around the Italian island of Ponza, just west of Naples. Like some of the island’s summertime partiers, the worms are nocturnal and out of sight when the sun is high in the sky. So what does this polychaete do with its walloping peepers after dark? And what are they good for?

Neuro- and marine biologist Anders Garm from the University of Copenhagen’s biology department couldn’t ignore the question. Setting other plans aside, the researcher felt compelled to dive in and try to find out. He was hooked as soon as his colleague Michael Bok at Lund University showed him a recording of the bristle worm.

“Together, we set out to unravel the mystery of why a nearly invisible, transparent worm that feeds in the dead of night has evolved to acquire enormous eyes. As such, the first aim was to answer whether large eyes endow the worm with good vision,” says Michael Bok who together with Garm, authors a new study published in the journal Current Biology that does just that.

It turns out that the Vanadis’ eyesight is excellent and advanced. Research has demonstrated that this worm can use its eyes to see small objects and track their movements.

“It’s really interesting because an ability like this is typically reserved for us vertebrates, along with arthropods (insects, spiders, etc.) and cephalopods (octopus, squid). This is the first time that such an advanced and detailed view has been demonstrated beyond these groups. In fact, our research has shown that the worm has outstanding vision. Its eyesight is on a par with that of mice or rats, despite being a relatively simple organism with a miniscule brain,” Garm says.

This is what makes the worm’s eyes and extraordinary vision unique in the animal kingdom. And it was this combination of factors about the Vanadis bristle worm that really caught Garm’s attention.

The researcher’s work focuses on understanding how otherwise simple nervous systems can have very complex functions—which was definitely the case here.

Nightlife of the bristle worm

For now, the researchers are trying to find out what caused the worm to develop such good eyesight. The worms are transparent, except for their eyes, which need to register light to function. So they can’t be inherently transparent. That means that they come with evolutionary trade-offs.

As becoming visible must have come at a cost to the Vanadis, something about the evolutionarily benefits of its eyes must outweigh the consequences.

Precisely what the worms gain remains unclear, particularly because they are nocturnal animals that tuck away during the day, when eyes usually work best.

“No one has ever seen the worm during the day, so we don’t know where it hides. So, we cannot rule out that its eyes are used during the day as well. What we do know is that its most important activities, like finding food and mating, occur at night. So, it is likely that this is when its eyes are important,” Garm says.

Part of the explanation may be due to the fact that these worms see different wavelengths of light than we humans do. Their vision is geared to ultraviolet light, invisible to the human eye. And according to Garm, this may indicate that the purpose of its eyes is to see bioluminescent signals in the otherwise pitch-black nighttime sea.

“We have a theory that the worms themselves are bioluminescent and communicate with each other via light. If you use normal blue or green light as bioluminescence, you also risk attracting predators. But if instead, the worm uses UV light, it will remain invisible to animals other than those of its own species. Therefore, our hypothesis is that they’ve developed sharp UV vision so as to have a secret language related to mating,” says Garm.

“It may also be that they are on the lookout look for UV bioluminescent prey. But regardless, it makes things truly exciting as UV bioluminescence has yet to be witnessed in any other animal. So, we hope to be able to present this as the first example,” he says.

Simple brains, advanced vision

As a result of the discovery, Garm and colleagues have also started working with robotics researchers from the Maersk Mc-Kinney Møller Institute at the University of Southern Denmark (SDU) who find technological inspiration in biology. Together, they share a common goal of investigating whether it is possible to understand the mechanism behind these eyes well enough so as to translate it into technology.

“Together with the robotics researchers, we are working to understand how animals with brains as simple as these can process all of the information that such large eyes are likely able to collect, Garm says.

“This suggests that there are super smart ways to process information in their nervous system. And if we can detect these mechanisms mathematically, they could be integrated into computer chips and used to control robots.”

Vanadis’ eyes are also interesting with regards to evolutionary theory because they could help settle one of the heaviest academic debates surrounding the theory: Whether eyes have only evolved once—and evolved into every form that we know of today, or whether they have arisen several times, independently of one another, in evolutionary history.

Vanadis’ eyes are built simply, but equipped with advanced functionality. At the same time, they have evolved in a relatively short evolutionarily time span of just a few million years.

This means that they must have developed independently of, for example, human eyes, and that the development of vision, even with a high level of function, is possible in a relatively short time.

Source: University of Copenhagen