Researchers have developed synthetic platelets that can be used to stop bleeding and enhance healing at the site of an injury.

The researchers have demonstrated that the synthetic platelets work well in animal models but have not yet begun clinical trials in humans.

A number of medical situations require platelet transfusions—such as cases of severe bleeding, or for patients who are going into surgery or receiving chemotherapy.

Currently, patients in any of those situations receive platelets harvested from blood donors, ideally from donors with a compatible blood type. This is challenging, because there is a very limited supply of platelets available, those platelets have a limited shelf life, and the platelets must be stored under controlled conditions.

“We’ve developed synthetic platelets that can be used with patients of any blood type and are engineered to go directly to the site of injury and promote healing,” says Ashley Brown, an associate professor in the joint biomedical engineering program at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and corresponding author of the study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

“The synthetic platelets are also easy to store and transport, making it possible to give the synthetic platelets to patients in clinical situations sooner—such as in an ambulance or on the battlefield.”

The platelets are made of hydrogel nanoparticles that mimic the size, shape, and mechanical properties of human platelets. Hydrogels are water-based gels that are composed of water and a small proportion of polymer molecules.

“Our synthetic platelets are deformable—meaning they can change shape—in the same way that normal platelets are,” Brown says.

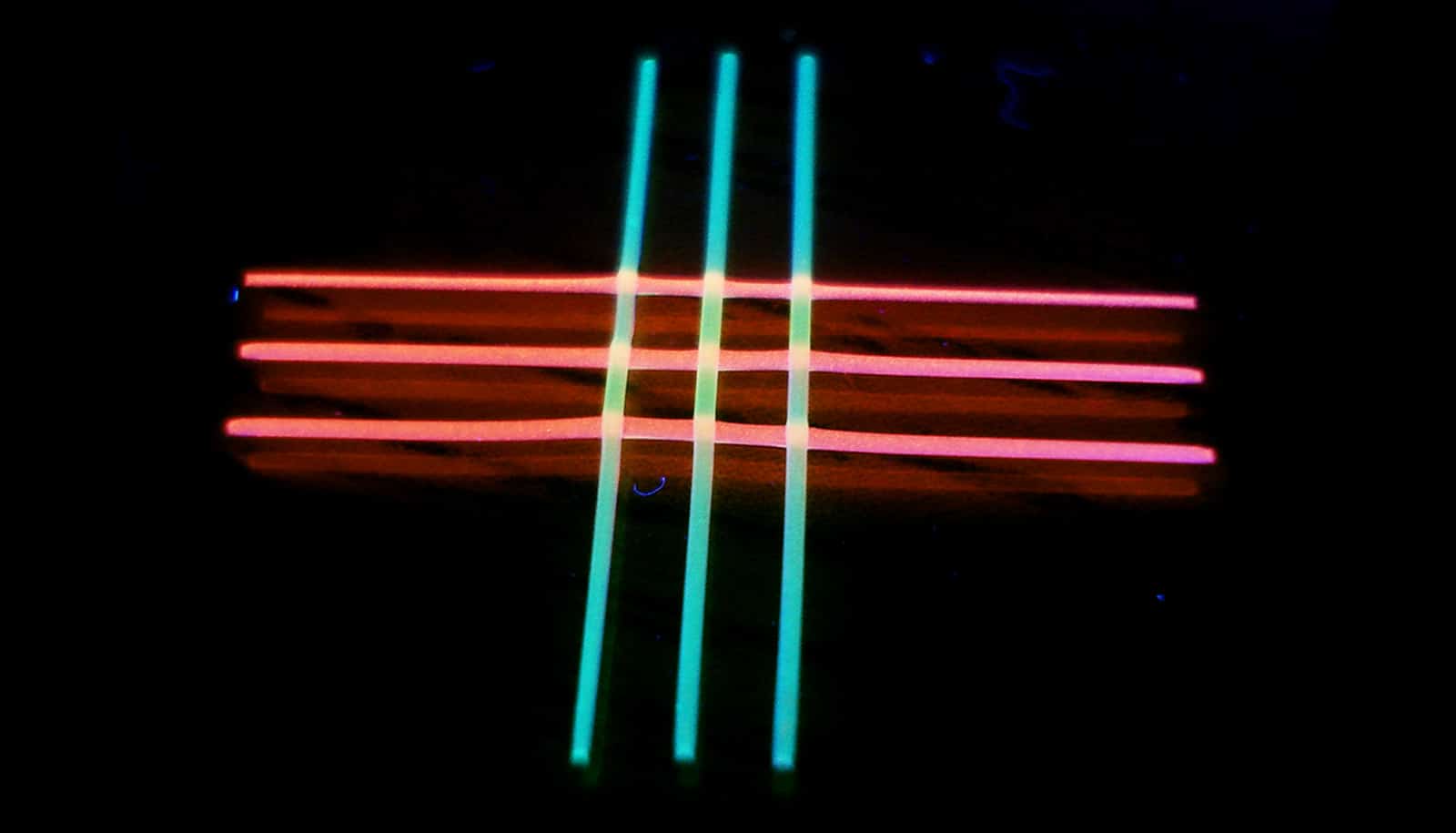

The researchers engineered the surface of the synthetic platelets to incorporate antibody fragments that bind to a protein called fibrin. When a body is injured, it synthesizes fibrin at the site of the wound. The fibrin then forms a mesh-like substance to promote clotting.

“Because the synthetic platelets are coated with these antibody fragments, the synthetic platelets travel freely through the blood stream until they reach the wound site,” Brown says. “Once there, the antibody fragments bind to the fibrin, and the synthetic platelets expedite the clotting process.”

In addition to forming a clot within the fibrin network, the synthetic platelets act to contract the clot over time—just like normal platelets.

“This expedites the process of healing, allowing the body to move forward with tissue repair and recovery,” Brown says.

The researchers initially demonstrated the efficacy of the antibody fragments via in vitro testing, as well as demonstrating that the antibody fragments and synthetic platelets could be produced at scales that would make them viable for large-scale manufacturing.

The researchers then used a mouse model to determine the optimal dose of synthetic platelets necessary to stop bleeding.

Subsequent research in both mouse and pig models demonstrated that the synthetic platelets traveled to the site of a wound, expedited clotting, did not cause any clotting problems in areas outside of the wound, and accelerated healing.

“In the mouse and pig models, healing rates were comparable in animals that received platelet transfusions and synthetic platelet transfusions,” Brown says. “And both groups fared better than animals that did not receive either transfusion. We also found that the animals in both mouse and pig models were able to safely clear the synthetic platelets over time through normal kidney function. We didn’t see any adverse health effects associated with the use of the synthetic platelets.

“In addition, based on our preliminary estimates, we anticipate that the cost of the synthetic platelets—if they are approved for clinical use—would be comparable to the current cost of platelets,” Brown says.

“We are wrapping up preclinical efficacy testing and are in the process of securing funding for preclinical safety work that should allow us to obtain FDA approval to begin clinical trials within two years.”

Additional coauthors are from NC State, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Virginia, Duke University, and Chapman University.

Brown and coauthors Seema Nandi, Andrew Lyon of Chapman University, and Thomas Barker, of the University of Virginia, are all cofounders of a start-up company called SelSym Biotech that is focused on developing and marketing synthetic platelets for clinical use. Nellenbach owns stock in SelSym Biotech.

This research was done with support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute of General Medical Sciences; the National Institutes of Health; the Department of Defense; the National Science Foundation; the American Heart Association; the US Department of Veterans Affairs; and the North Carolina State University Chancellor’s Innovation Fund.

Source: NC State