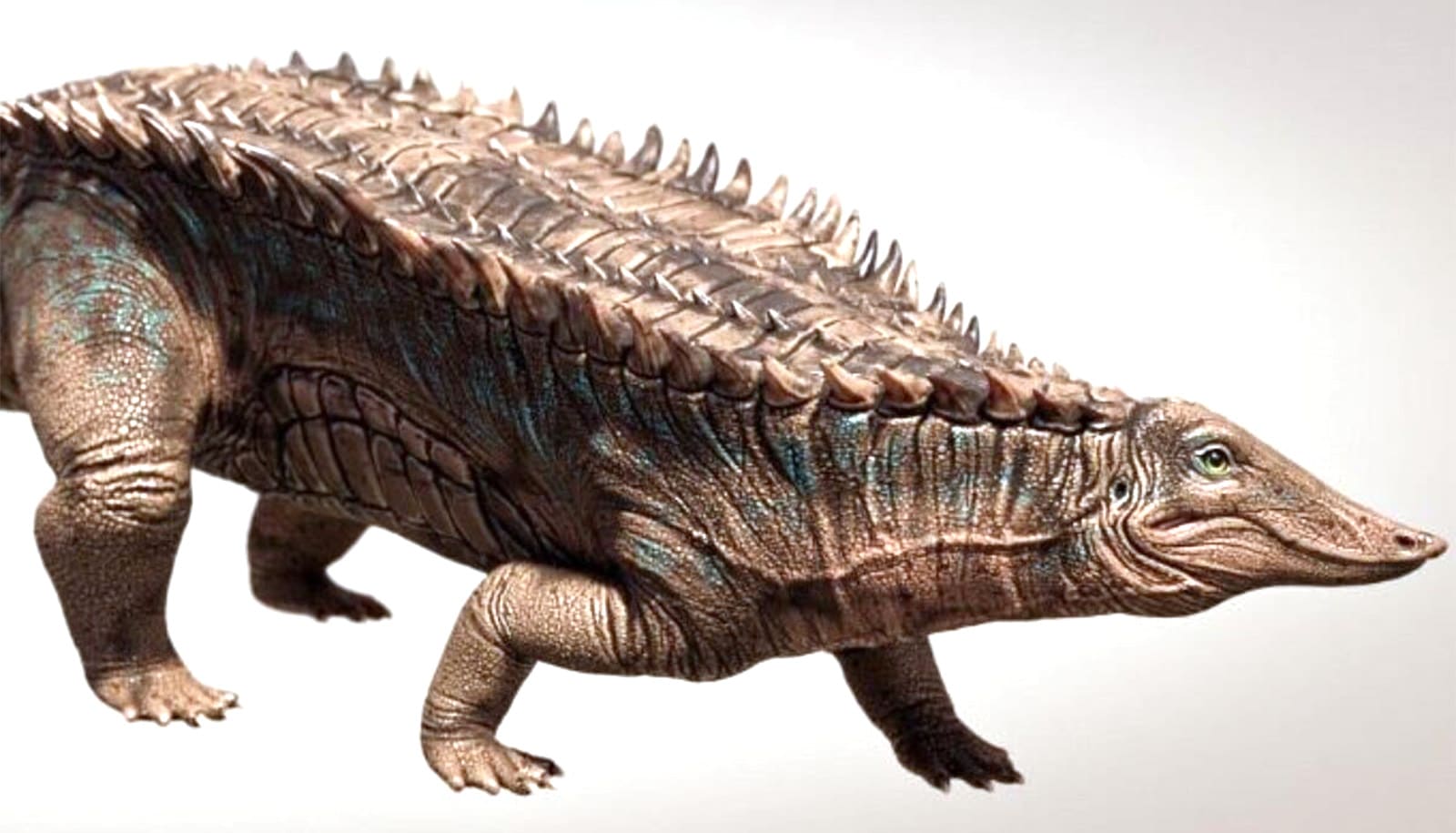

Researchers used bony armor plates to identify a new aetosaur species—which they named Garzapelta muelleri.

Dinosaurs get all the glory. But aetosaurs, a heavily armored cousin of modern crocodiles, ruled the world before dinosaurs did.

These tanks of the Triassic came in a variety of shapes and sizes before going extinct around 200 million years ago. Today, their fossils are found on every continent except Antarctica and Australia.

Scientists use the bony plates that make up aetosaur armor to identify different species and usually don’t have many fossil skeletons to work with.

But the new study led by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin centers on an aetosaur suit of armor that has most of its major parts intact.

The suit—called a carapace—is about 70% complete and covers each major region of the body.

“We have elements from the back of the neck and shoulder region all the way to the tip of the tail,” says William Reyes, a doctoral student at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences who led the research published in The Anatomical Record. “Usually, you find very limited material.”

Reyes and his collaborators used the armor to identify the specimen as Garzapelta muelleri. The name “Garza” recognizes Garza County in northwest Texas, where the aetosaur was found, and “Pelta” is Latin for shield, a nod to aetosaurs’ heavily fortified body. The species name “muelleri” honors the paleontologist who originally discovered it, Bill Mueller.

Garzapelta lived about 215 million years ago and resembled a modern American crocodile—but with much more armor. The bony plates that covered Garzapelta and other aetosaurs are called osteoderms. They were embedded directly in the skin and formed a suit of armor by fitting together like a mosaic.

In addition to having a body covered in bony plates, Garzapelta’s sides were flanked by curved spikes that would have offered another layer of protection from predators. Although crocodiles today are carnivores, scientists think that aetosaurs were primarily omnivorous.

The spikes on Garzapelta are very similar to those found in another aetosaur species, but surprisingly, researchers found that the two species are only distantly related. The similarities, they discovered, are an example of convergent evolution, the independent evolution of similar traits in different species. The development of flight in insects, birds, mammals, and now-extinct pterosaurs is a classic example of this phenomenon.

An array of unique features on Garzapelta‘s plates clearly marked it as a new species, Reyes says. They range from how the plates fit together to unique bumps and ridges on the bones. However, figuring out where Garzapelta fit into the larger aetosaur family tree was more of challenge.

Depending on which portion of the armor the researchers emphasized in their analysis, Garzapelta would end up in very different places. Armor that ran down its back resembled armor from one species, while its midsection spikes resembled armor from another.

Once the researchers determined that the spikes evolved independently, they were able to work out where Garzapelta fit best among other aetosaur species. Nevertheless, Reyes says the research shows how convergent evolution can complicate things.

“Convergence of the osteoderms across distantly related aetosaurs has been noted before, but the carapace of Garzapelta muelleri is the best example of it and shows to what extent it can happen and the problems it causes in our phylogenetic analyses,” Reyes says.

Garzapelta is part of the Texas Tech University fossil collections. It spent most of the past 30 years on a shelf before Reyes encountered it during a visit.

Bill Parker, an aetosaur expert and park paleontologist at Petrified Forest National Park who was not part of the research, says that university and museum collections are a critical part of making this type of research possible.

In addition to different species having different armor, it’s possible that an animal’s age or sex could also affect armor appearance. Reyes is currently exploring these questions by studying aetosaur fossils in the Jackson School’s collection, most of which were found during the 1940s as part of excavations done by the Works Progress Administration.

The National Science Foundation and the Jackson School funded the work.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Houston-Downtown, and the Museum of Texas Tech University.

Source: UT Austin