People who received gentle electric currents on the back of their heads learned to maneuver a robotic surgery tool in virtual reality and then in a real setting much more easily than people who didn’t receive those nudges, a new study shows.

The findings offer the first glimpse of how stimulating a specific part of the brain called the cerebellum could help health care professionals take what they learn in virtual reality to real operating rooms, a much-needed transition in a field that increasingly relies on digital simulation training, says author and Johns Hopkins University roboticist Jeremy D. Brown.

“It was really cool that we were actually able to influence behavior using this setup…”

“Training in virtual reality is not the same as training in a real setting, and we’ve shown with previous research that it can be difficult to transfer a skill learned in a simulation into the real world,” says Brown, an associate professor of mechanical engineering.

“It’s very hard to claim statistical exactness, but we concluded people in the study were able to transfer skills from virtual reality to the real world much more easily when they had this stimulation.”

The work appears in Nature Scientific Reports.

Participants drove a surgical needle through three small holes, first in a virtual simulation and then in a real scenario using the da Vinci Research Kit, an open-source research robot. The exercises mimicked moves needed during surgical procedures on organs in the belly, the researchers say.

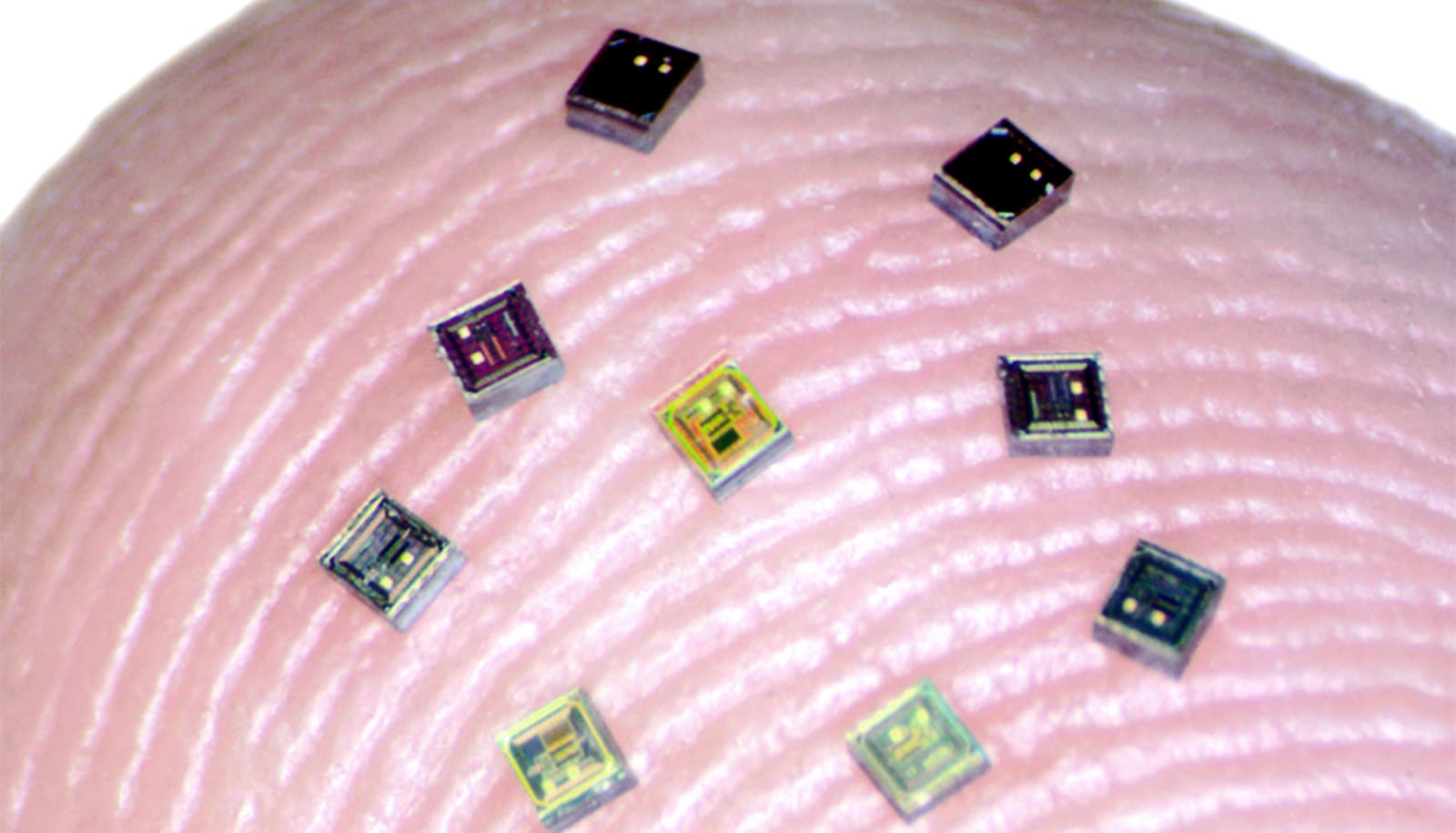

Participants received a subtle flow of electricity through electrodes or small pads placed on their scalps meant to stimulate their brain’s cerebellum. While half the group received steady flows of electricity during the entire test, the rest of the participants received a brief stimulation only at the beginning and nothing at all for the rest of the tests.

People who received the steady currents showed a notable boost in dexterity. None of them had prior training in surgery or robotics.

“The group that didn’t receive stimulation struggled a bit more to apply the skills they learned in virtual reality to the actual robot, especially the most complex moves involving quick motions,” says Guido Caccianiga, a former Johns Hopkins roboticist, now at Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems, who designed and led the experiments. “The groups that received brain stimulation were better at those tasks.”

Noninvasive brain stimulation is a way to influence certain parts of the brain from outside the body, and scientists have shown how it can benefit motor learning in rehabilitation therapy, the researchers say. With their work, the team is taking the research to a new level by testing how stimulating the brain can help surgeons gain skills they might need in real-world situations, says coauthor Gabriela Cantarero, a former assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Johns Hopkins.

“It was really cool that we were actually able to influence behavior using this setup, where we could really quantify every little aspect of people’s movements, deviations, and errors,” Cantarero says.

Robotic surgery systems provide significant benefits for clinicians by enhancing human skill. They can help surgeons minimize hand tremors and perform fine and precise tasks with enhanced vision.

Besides influencing how surgeons of the future might learn new skills, this type of brain stimulation also offers promise for skill acquisition in other industries that rely on virtual reality training, particularly work in robotics.

Even outside of virtual reality, the stimulation can also likely help people learn more generally, the researchers say.

“What if we could show that with brain stimulation you can learn new skills in half the time?” Caccianiga says. “That’s a huge margin on the costs because you’d be training people faster; you could save a lot of resources to train more surgeons or engineers who will deal with these technologies frequently in the future.”

Additional authors are from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab.

Source: Johns Hopkins University