A new “lab on a chip” can be 3D-printed in just 30 minutes, researchers report.

The breakthrough in diagnostic technology has the potential to make on-the-spot testing widely accessible.

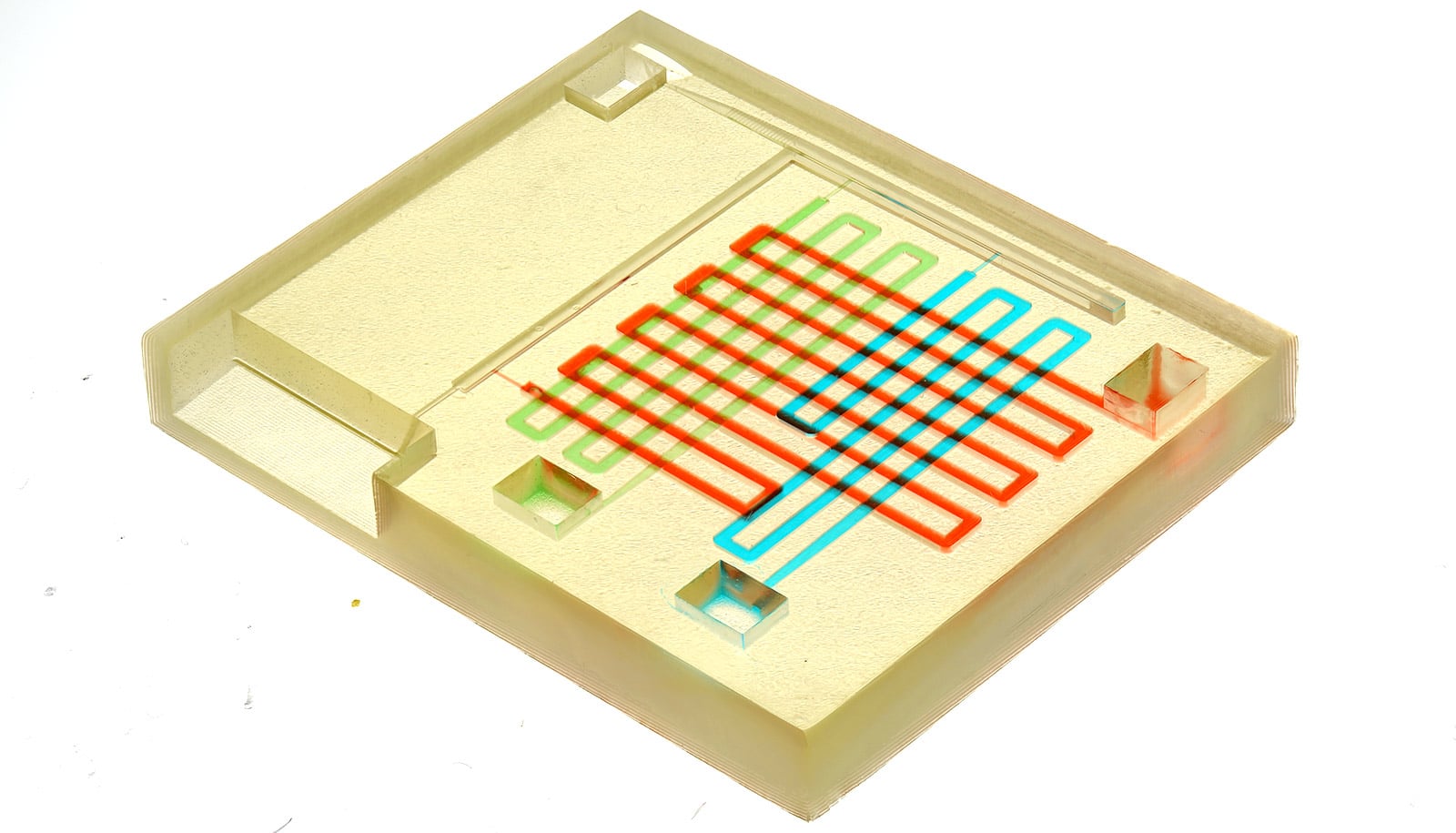

As part of a recent study, the researchers developed capillaric chips that act as miniature laboratories. Unlike other computer microprocessors, these chips are single-use and require no external power source—a simple paper strip suffices.

The chips function through capillary action—the phenomena by which a spilled liquid on the kitchen table spontaneously wicks into the paper towel used to wipe it up.

“Traditional diagnostics require peripherals, while ours can circumvent them,” says David Juncker, chair of the biomedical engineering department at McGill University and senior author of the study in the journal Advanced Materials.

“Our diagnostics are a bit what the cell phone was to traditional desktop computers that required a separate monitor, keyboard, and power supply to operate.”

At-home testing became crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic. But rapid tests have limited availability and can only drive one liquid across the strip, meaning most diagnostics are still done in central labs. Notably, the capillaric chips can be 3D-printed for various tests, including COVID-19 antibody quantification.

The study brings 3D-printed home diagnostics one step closer to reality, though some challenges remain, such as regulatory approvals and securing necessary test materials. The team is actively working to make their technology more accessible, adapting it for use with affordable 3D printers. The innovation aims to speed up diagnoses, enhance patient care, and usher in a new era of accessible testing.

“This advancement has the capacity to empower individuals, researchers, and industries to explore new possibilities and applications in a more cost-effective and user-friendly manner,” Junker says.

“This innovation also holds the potential to eventually empower health professionals with the ability to rapidly create tailored solutions for specific needs right at the point-of-care.”

Source: McGill University