As the climate warms, forest cover will become increasingly important for wildlife conservation, researchers report.

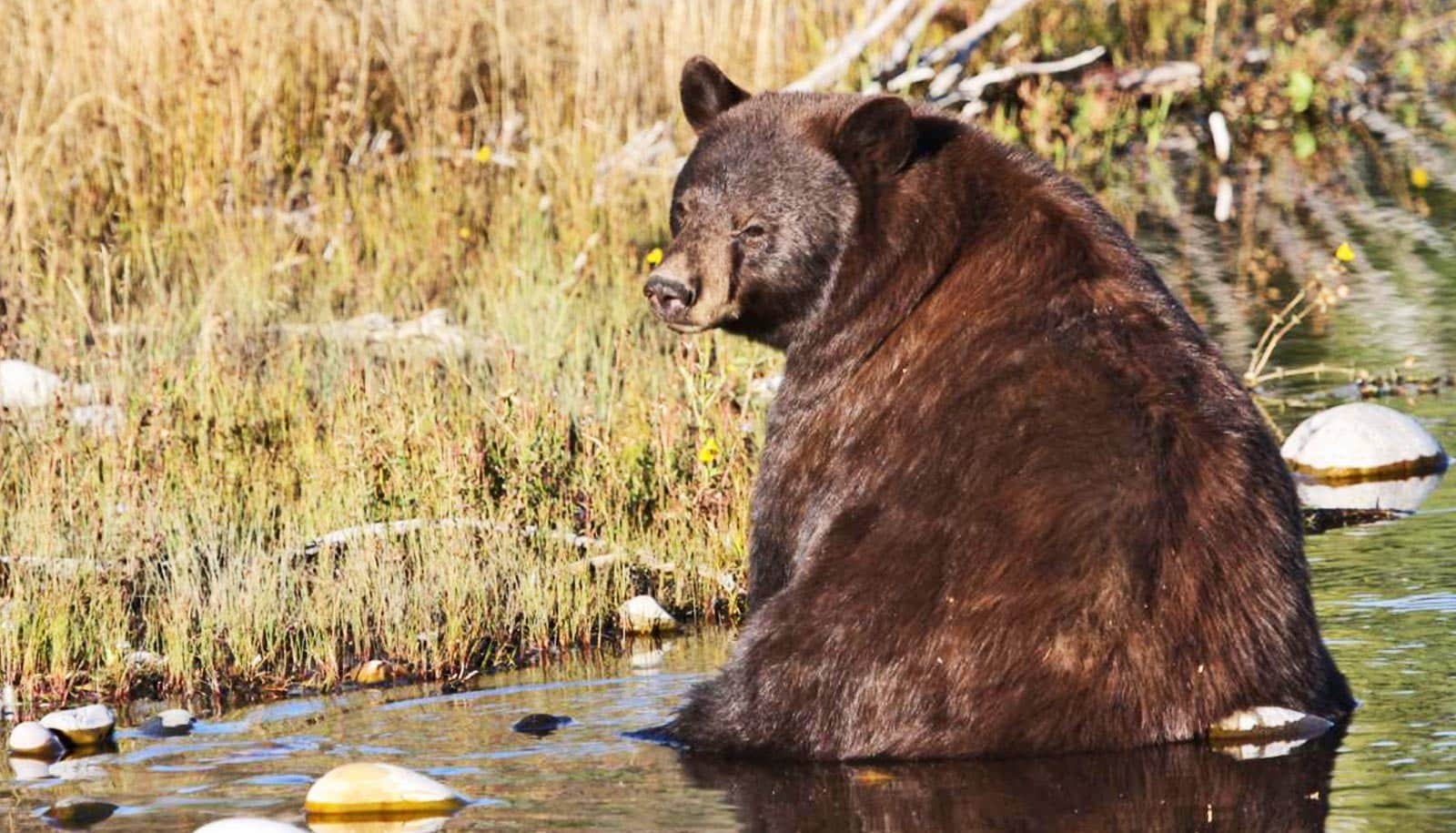

The findings show that North American mammals, including pumas, wolves, bears, rabbits, deer, and opossums consistently depend on forests and avoid cities, farms, and other human-dominated areas in hotter climes.

In fact, mammals are, on average, 50% more likely to occupy forests than open habitats in hot regions. The opposite is true in the coldest regions.

“Different populations of the same species respond differently to habitat based on where they are,” says lead author Mahdieh Tourani, who conducted the study while a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Davis who is now an assistant professor of quantitative ecology at the University of Montana, Missoula. “Climate is mediating that difference.”

Tourani points to the eastern cottontail as an example. The study showed the common rabbit preferred forests in hotter areas while preferring human-dominated habitat, such as agricultural areas, in colder regions.

Her example illustrates “intraspecific variation,” which the study found to be pervasive across all North America’s mammals. This runs contrary to a longstanding practice in conservation biology of categorizing species as those that live well alongside people and those that don’t. The authors say there is growing recognition of ecological flexibility, and that species are more complicated than those two categories suggest.

“We can’t take a one-size-fits all approach to habitat conservation,” says senior author Daniel Karp, associate professor in the wildlife, fish, and conservation biology department at UC Davis. “It turns out climate has a large role in how species respond to habitat loss.”

For example, if elk are managed under the assumption that they can only live in protected areas, then conservation managers may miss opportunities to conserve them in human-dominated landscapes.

“On the other hand, if we assume a species will always be able to live alongside us, then we might be wasting our effort trying to improve the conservation value of human-dominated landscapes in areas where it is simply too hot for the species,” Karp says.

For the study, the authors leveraged Snapshot USA, a collaborative monitoring program with thousands of camera trap locations across the country.

“We analyzed 150,000 records of 29 mammal species using community occupancy models,” Tourani says. “These models allowed us to study how mammals respond to habitat types across their ranges while accounting for the fact that species may be in an area, but we did not record their presence because the species is rare or elusive.”

The study provides a pathway for conservation managers to tailor efforts to conserve and establish protected areas, as well as enhance working landscapes, like farms, pastures, and developed areas.

“If we’re trying to conserve species in working landscapes, it might behoove us to provide more shade for species,” says Karp, whose recent study about birds and climate change drew a similar conclusion, with forests providing a protective buffer against high temperatures.

“We can maintain patches of native vegetation, scattered trees, and hedgerows that provide local refugia for wildlife, especially in places that are going to get warmer with climate change.”

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Additional coauthors are from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, North Carolina State University, Arizona State University, and Conservation International.

Conservation International funded the work.

Source: UC Davis