A new prescription wristwatch continuously monitors the wearer’s heart rhythm and uses an algorithm to detect atrial fibrillation.

As the use of wearable technology grows, smartwatches are marketed across the globe to consumers as a way to monitor health.

For some, these devices let them know they have atrial fibrillation, an irregular heartbeat, which is known to increase the risk of heart attack and stroke.

“Unfortunately, this has led to a tsunami of healthy patients coming to clinics complaining about having atrial fibrillation, and we see many false positives without really having a way to use these devices clinically,” says Hamid Ghanbari, an assistant professor of internal medicine-cardiology at the University of Michigan Medical School and lead author of the study in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

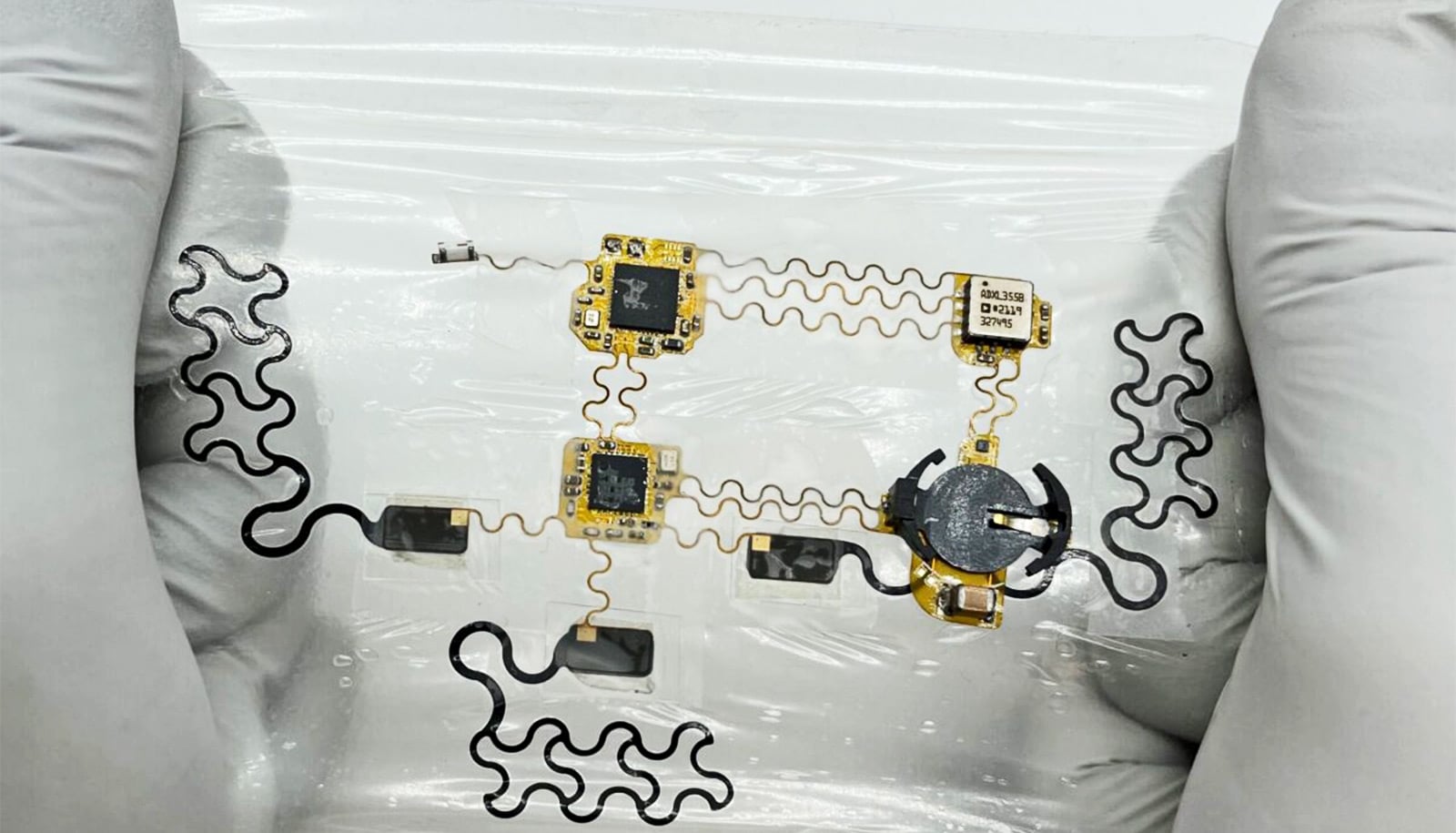

The clinical-grade device, called the Verily Study Watch, addresses that clinical gap and has proved very accurate at identifying atrial fibrillation in study participants.

“Right now, we typically manage patients with atrial fibrillation using electrocardiogram, or ECG, patches that we put on the chest, but the future of Afib management will be on the wrist,” Ghanbari says.

Much like consumer wearable devices, the Verily Study Watch detects subtle changes in heart rhythm by sending light pulses through the skin into the blood vessels, a process known as photoplethysmography.

If it suspects atrial fibrillation, the device would prompt a user to take a single-lead ECG to determine if the algorithm correctly identified to Afib.

The results would then be reviewed by a cardiographic technician before it was reported to the participant’s physician.

For the study, the device analyzed data every 15 minutes, and its deep neural network algorithm determined whether over 100 participants had atrial fibrillation between September 2020 and May 2021.

The study watch correctly identified atrial fibrillation in the vast majority of participants, with levels of false negatives and positives that was similar to other devices for detection of Afib using similar photoplethysmography technology.

Although there was a decrease in performance of the device for some episodes of atrial fibrillation for participants with darker skin tones, it was still able to detect Afib in those patients.

The researchers say this is the first study to report the performance of the photoplenthysmography-based algorithm for participants at all levels of physical activity. The device’s accuracy of detecting atrial fibrillation was comparable during low and moderate levels of activity.

Consumer-facing devices, like Apple Watch and Fitbit, are cleared by the United States Food and Drug Administration for pre-diagnostic purposes but are not intended for clinical decision making.

This device, Ghanbari says, could provide the link that allows providers to effectively use data from wearables to manage patients with Afib.

“The prescription Study Watch bridges the gap between long term, continuous monitoring that is currently more invasive and the consumer space with a practical solution for Afib detection and burden assessment,” he says.

“It is not intended to replace interval ECG monitoring for patients who need it. However, the multistage system may also limit the burden on clinicians and avoid the deluge of notifications generated by other wrist-worn devices that rarely result in clinically actionable findings.”

The creator of the watch, Verily Life Sciences, received 510(k) clearance from the FDA, a premarket submission to demonstrate the product’s efficacy and similarity to a legally marketed device.

“There is a need for clinical grade wrist-worn wearable that is affordable and can be prescribed by clinicians for the long term, personalized and continuous management of patients with Afib,” Ghanbari says.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Michigan, the University of Pittsburgh, Verily Life Sciences, Google, iRhythm Technologies, the Colorado Heart and Vascular, the San Diego Cardiac Center, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and Ascension Providence Hospital.

Ghanbari is a paid consultant for Verily Life Sciences, Boston Scientific, Johnson and Johnson, and Huxley Medical Inc.

Source: University of Michigan