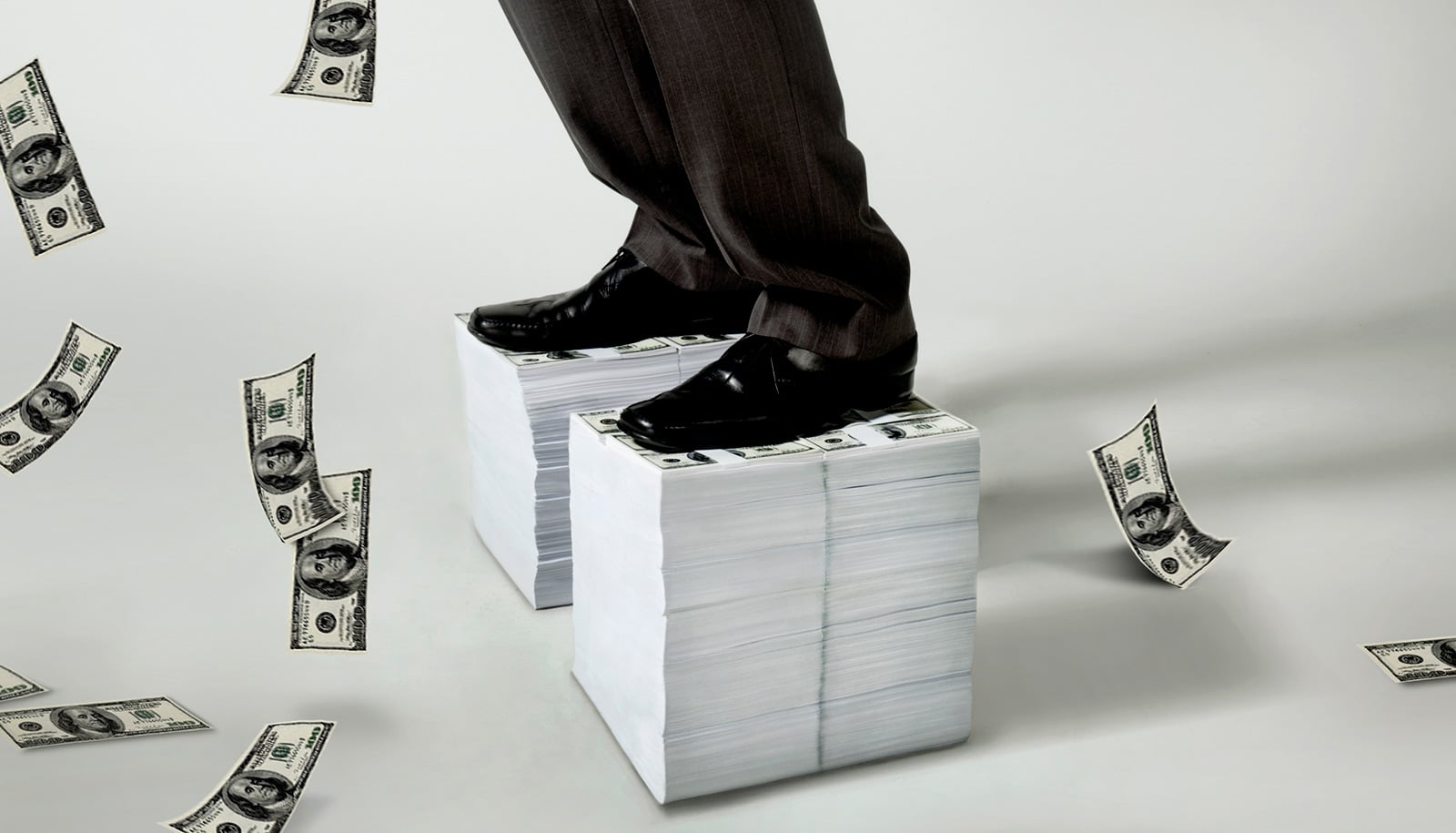

Only a third of adults in the United States did not rely on their parents for some form of material support between their late teens and early 40s, research finds.

The study highlights the extent to which parents and adult children rely on each other for financial assistance or a place to live well into the children’s adult years and challenges popular conventions and expectations about adulthood.

“This work really challenges the notion that complete independence is a necessary marker of adulthood,” says Anna Manzoni, coauthor of the study and an associate professor of sociology at North Carolina State University. “Instead, we see a pattern of interdependency that changes over time and appears to be influenced by race and educational background.”

For the study, researchers analyzed data on 14,675 US adults who participated in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, focusing on data collected from study participants between the ages of 18 and 43.

Specifically, the researchers looked at various ways in which these adults exchanged financial and residential support with their parents over time, as well as various social and demographic factors, such as gender, race/ethnicity, and parents’ educational background.

“We found that there is no single pathway that most people take regarding independence from their parents,” Manzoni says. “Instead, people tend to fall into one of six different categories.”

The researchers call these categories “pathways of intergenerational support”:

- Complete Independence (comprising 33.44% of survey respondents) refers to children who become financially and residentially independent in their late teens or early 20s and retain that independence;

- Independent with Transitional Support (20.14%) is similar to the “Complete Independence” group, but received some financial support from parents in their 20s or early 30s;

- Gradual Independence (15.07%) refers to children who lived at home into their 20s and received significant financial support, with that support declining very gradually over time;

- High to Low Support (14.63%) refers to children who lived at home into their 20s and received significant financial support, but that support declined rapidly as the children grow older;

- Extended Interdependence (10.22%) refers to children who lived at home for extended periods of time and who not only received financial support from parents but also provided financial support to parents; and

- Boomerang (6.51%) refers to children who moved out in their late teens or early 20s, moved back in with parents in their mid-20s to early 30s, and then moved out again in their 30s or early 40s.

“We also found that these pathways are not evenly distributed across the population,” Manzoni says. “For example, Complete Independence is least likely among Black families and most likely among white families, while Extended Interdependence is least likely among white families and most likely among Hispanic families.

“Educational background also appears to be a significant factor. For example, people whose parents completed less than a high school education are far more likely to experience the Extended Interdependence pathway, while people whose parents completed a graduate or professional degree are significantly more likely to experience the Complete Independence pathway.

“Ultimately, the work drives home the extent to which access to resources and structural restraints—such as access to education—influence which pathways to independence people have access to. It also makes clear that we need to reevaluate how we think of independence and adulthood, given that only a third of study participants were able to take the Complete Independence pathway that is often presented as being the norm.”

The paper appears in Sociological Perspectives.

Source: NC State