A new wearable, textile-based device that uses touch could help declutter, enhance—and, in the case of impairments—compensate for deficiencies in visual and auditory inputs, new research shows.

Personal devices feed our sight and hearing virtually unlimited streams of information while leaving our sense of touch mostly untouched. The new device taps into this underused sensory resource.

“Technology has been slow to co-opt haptics or communication based on the sense of touch,” says Barclay Jumet, a mechanical engineering PhD student at Rice University and lead author of the study published in the journal Device.

“Of the technologies that have incorporated haptics, wearable devices often still require bulky external hardware to provide complex cues, limiting their use in day-to-day activities.”

The new system of haptic accessories reduces the need for hardware by programming into the textile structure of the wearables using fluidic control, building on an approach described in prior work.

“With a traditional control system using voltage and current, you’d typically need many electronic inputs to achieve complex haptic cues,” says Daniel Preston, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering whose lab explores the intersection of energy, materials, and fluids.

“In this device, we’ve offloaded a lot of that complexity to the fluidic controller and require only a very limited number of electronic inputs to provide sophisticated haptic stimulation.”

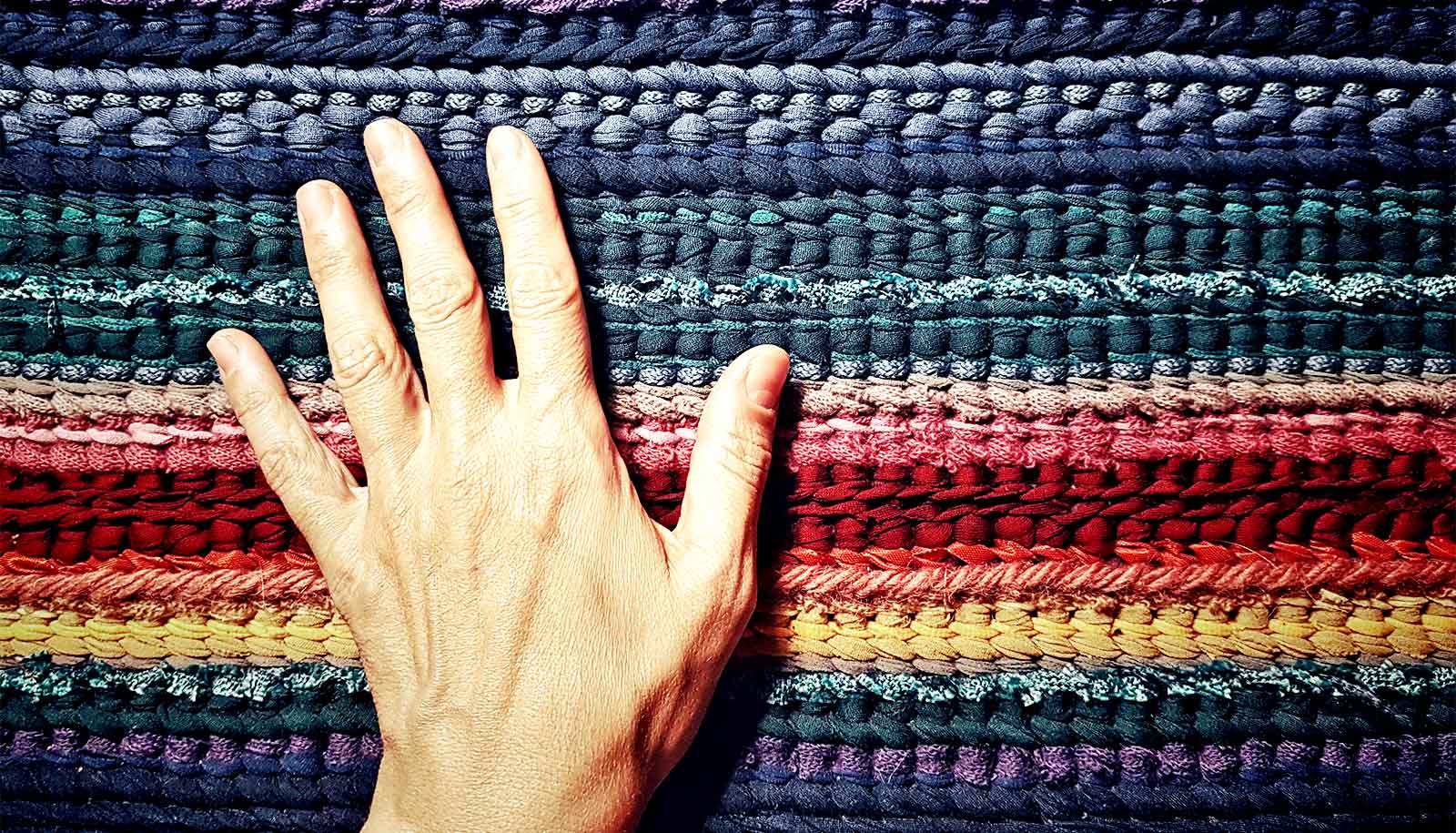

Comprised of a belt and textile sleeves, the wearables rely on fluidic signals—such as pressures and flow rates—to control the delivery of complex haptic cues, including sensations like vibration, tapping, and squeezing.

A small, lightweight carbon dioxide tank affixed to the belt feeds airtight circuits incorporated in the heat-sealable textiles, causing quarter-sized pouches—up to six on each sleeve—to inflate with varying force and frequency.

In an experiment demonstrating the device’s utility for real-world navigation, these cues served as directions guiding a user on a mile-long route through the streets of Houston. In another experiment, a user outlined invisible Tetris pieces in a field by following the directions conveyed to them through the haptic textiles.

“The belt incorporates a slimmed-down version of the electronic control system that might otherwise be required,” Jumet says. “In this case, we had twelve pouches across two sleeves progressively inflate to indicate one of four directions: forward, backward, left, or right. So instead of requiring twelve electronic inputs, we embed that complexity into the sleeve and are able to use only four inputs—a reduction by two-thirds.

“In the future, this technology could be directly integrated with navigational systems, so that the very textiles making up one’s clothing can tell users which way to go without taxing their already overloaded visual and auditory senses—for instance by needing to consult a map or listen to a virtual assistant.”

Moreover, the wearable textile device could incorporate other sensing and control mechanisms to allow users with limited vision or hearing to detect obstacles and navigate dynamic environments in real time.

“Devices like this could, for instance, be helpful for people suffering from hearing loss,” says Marcia O’Malley, chair of the department of mechanical engineering and professor in mechanical engineering, electrical and computer engineering, bioengineering, and computer science.

Cochlear implants can restore speech perception for people with severe hearing loss, but the literature shows that these individuals still struggle to understand speech in noisy environments and can experience difficulty locating the sources of sounds. Haptic feedback has the potential to enhance cochlear implant performance or make lip-reading easier for patients.

“You’ll have better recognition and interpretation of the sounds processed by the cochlear implant if they’re reinforced with haptic cues conveying the same information encoded in a different way,” O’Malley says.

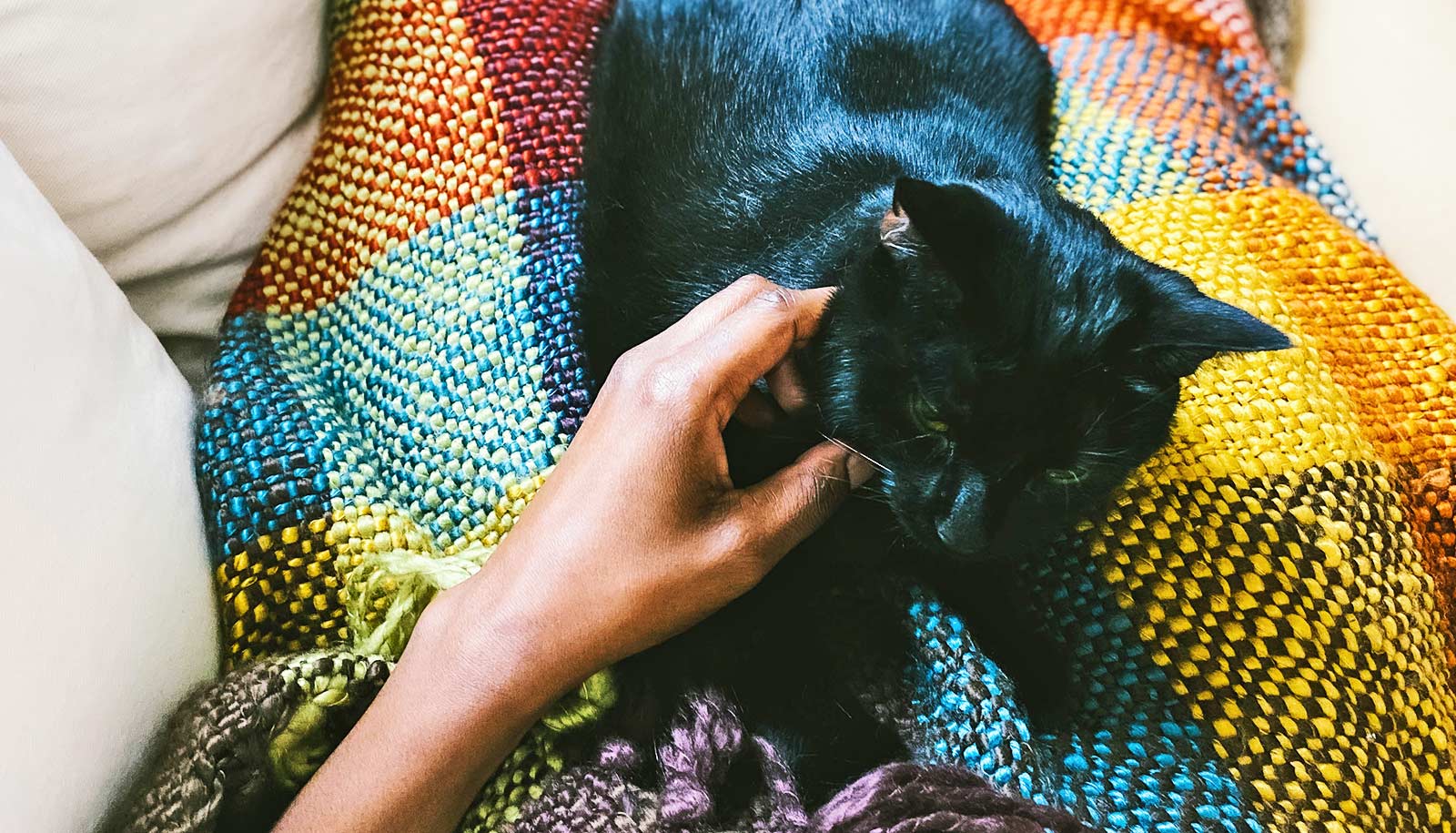

Another application example is restoring the sense of touch for an amputee by embedding sensors on a prosthesis to gather data that the wearables could relay as haptic feedback elsewhere on the body.

“The haptic feedback experienced by the user would in this case be directly correlated with the actions they’re taking,” says O’Malley, who directs the Mechatronics and Haptic Interfaces Lab at Rice.

“One of the big advantages with using these smart textiles for haptic devices is that they bring a lot more freedom and flexibility to the design space. We’re no longer constrained by the size or geometry of components that need to be incorporated into a design.”

The heat-sealable textiles are resilient to wear and tear, making the device suitable for intensive daily use.

“We tested the durability of our haptic textiles by washing a device 25 times then cutting it open with a knife and ironing a textile patch over the cut,” Jumet says. “It continued to work as intended after repeated washing, cutting, and repairing.”

Jumet expressed the hope that, in addition to serving as the basis for medically-useful applications, haptic textiles could “enable a more immersive and seamlessly-connected world.”

“Instead of a smart watch with simple vibrational cues, we can now envision a ‘smart shirt‘ that gives the sensation of a stroking hand or a soft tap on the torso or arm,” he says. “Movies, games, and other forms of entertainment could now incorporate the sense of touch, and virtual reality can be more comfortable for longer periods of time.”

The National Science Foundation, the Rice University Academy of Fellows, and the Gates Millennium Scholars Program funded the program.

Source: Rice University