Programs aimed to reduce the risk of repeat overdoses among people who use drugs have a “police paradox,” research shows.

Law enforcement officials play a critical role in launching programs designed to reduce the risk of repeat overdoses in people who use drugs, the study finds. However, the findings also raise concerns that law enforcement’s involvement in the outreach component of these programs may undermine program effectiveness.

“…police are being asked to participate in a program they are not trained for—they are not social workers or public health experts.”

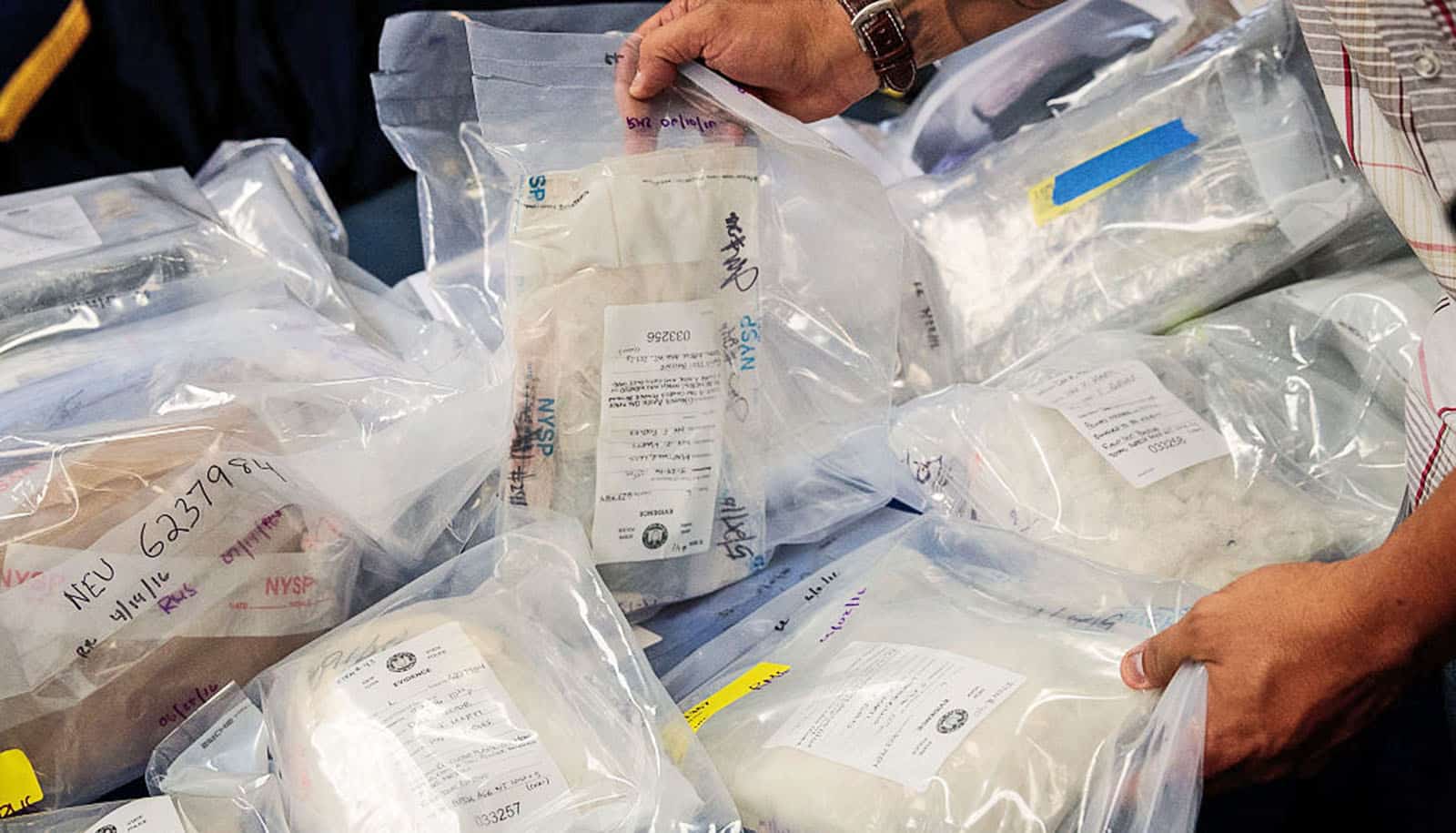

At issue are post-overdose outreach programs, which are designed to reach out to people who have recently survived an overdose. Specifically, the goal of the programs is to connect survivors to available resources—such as harm reduction and treatment—that reduce their likelihood of overdosing again.

“We have programs and treatment tools that work to reduce harms associated with drug use, but we often struggle to connect people to these resources,” says Alexander Walley, coauthor of the study and a professor of medicine at Boston University. “When a person overdoses, they are effectively flagging themselves as someone who could benefit from these harm reduction and treatment resources. Post-overdose outreach programs can help connect them to those resources.”

“These programs have expanded exponentially in recent years, and are likely to become even more common since they are eligible for funding from opioid settlement funds,” says Jennifer Carroll, an assistant professor of anthropology at North Carolina State University and corresponding author of the study. “However, best practices were not established for these programs until earlier this year, and we are still in the early stages of collecting evidence about how effective the programs are at actually doing what they aim to do.

“Our goal for this study was to get a better understanding of how these post-overdose programs are established and implemented,” Carroll says. “Basically, we want to know about their organizational infrastructure, why they’re organized this way or that way, and what seems to be helping or hurting the success of these programs.”

To that end, the researchers conducted 49 in-depth interviews with a variety of stakeholders involved in post-overdose outreach programs in Massachusetts. The study participants included 15 police officers; 23 community partners; eight overdose survivors who received outreach services; and three family members of overdose survivors who received outreach services.

“We found that access to law enforcement data is essential when getting post-overdose programs off the ground, because law enforcement data about suspected overdose events is unrestricted and not subject to any privacy laws that regulate medical information,” Carroll says. “It is crucial for programs to have the ability to identify and contact people who have recently survived an overdose, and most outreach efforts are designed to rely on law enforcement agencies for that purpose.”

However, the study also found that most post-overdose programs include police or deputies as part of the outreach teams that contact overdose survivors.

“Having law enforcement participate in outreach poses a variety of challenges,” Carroll says. “For one thing, police are being asked to participate in a program they are not trained for—they are not social workers or public health experts. For another, police are primarily tasked with enforcing local, state, and federal laws; overdose survivors have broken the law by using illegal drugs, and many survivors have had negative experiences with law enforcement. Altogether, this makes overdose survivors leery of working with police, and can also put police in morally or professionally conflicted positions.

“In other words, post-overdose programs have a ‘police paradox’—relying on law enforcement for information and support, but struggling with the fact that police involvement during the outreach process makes it harder to get the necessary buy-in from survivors and meet the program’s overdose prevention goals,” Carroll says.

The concerns raised in this study about police involvement during the outreach process are not unfounded. A 2022 study, which Carroll and Walley also coauthored, found that police sometimes arrested overdose survivors flagged by overdose-response programs.

“Ultimately, these findings suggest that—if we really want to reduce overdose risks—law enforcement should not be part of the post-overdose outreach teams,” Carroll says. “These findings were central to establishing current best practices for outreach, but many post-overdose programs don’t appear to be following best practices when it comes to keeping police out of the outreach teams.”

Best practice guidance developed by this research group are available at prontopostoverdose.org.

The paper appears in the International Journal of Drug Policy. Coauthors are from Harvard University; Social Science Research and Evaluation, Inc.; Brandeis University; Boston Medical Center and Boston University; Northeastern University; and Boston University.

Funding came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Source: NC State