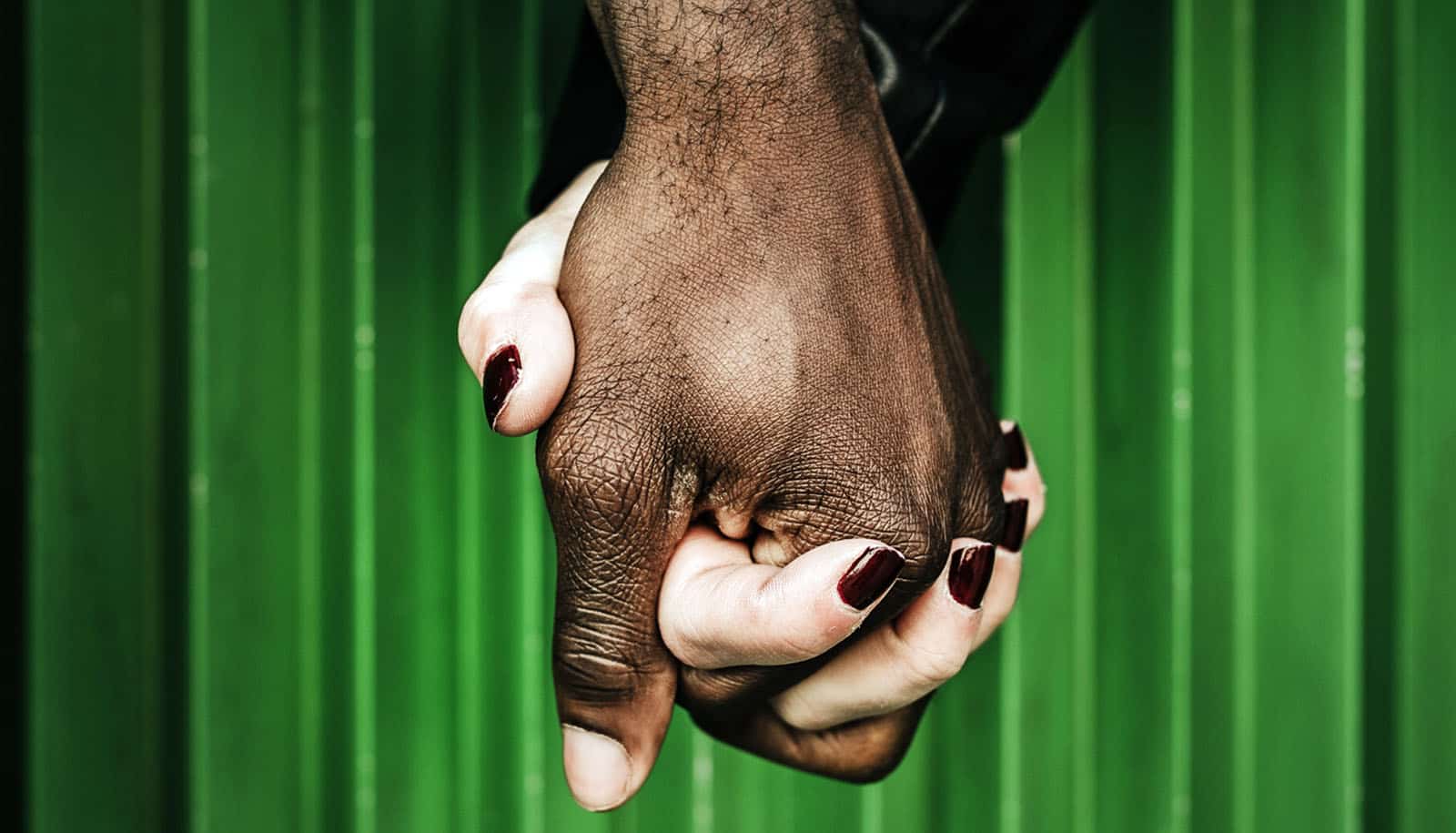

An increase in interracial relationships since 1967 has not ended discriminatory tendencies, even among individuals who are in these romantic partnerships, research shows.

That was the year that the landmark United States Supreme Court ruling in Loving v. Commonwealth of Virginia abolished bans on interracial marriage in the United States.

The paper appears in the Journal of Family Theory and Review. Researchers Jenifer Bratter, a professor of sociology at Rice University, and Mary Campbell, a professor of sociology at Texas A&M University, examined existing research on close interracial relationships to see how these friendships and/or romances affected overall attitudes about race and inequality.

“There are a lot of assumptions that people who enter into intimate interracial relations, at a minimum, do not hold stereotypes that would prevent them from dating or marrying someone of a different race,” Bratter says. “However, current research just doesn’t support this assumption.”

For example, the researchers note that one study finds that white people with best friends who are Black still express anti-Black racism, sometimes describing their friend as an “exception” to their beliefs about the larger group. And some of these close interracial relationships are sustained by avoiding any discussion of race or racial inequality, survey respondents reported.

Research on racial preferences in online dating shows that some daters use race as a limiting factor for identifying potential partners. For those who are open to interracial dating, research shows that they may still express preferences that align with existing racial stereotypes.

And Bratter and Campbell write that interracial marriage is not an indicator of openness among extended family members—quite the opposite, in fact.

“Some presume their presence will normalize interracial contact, undermine the racism of the extended family members who encounter the couples, and increase positive social contact between the different racial groups,” Campbell says. “Unfortunately, evidence from the experiences of interracial couples suggests this is not always the case.”

In addition to facing greater criticism from peers and extended families, Bratter says that these individuals in interracial marriages also reported receiving less support from their families when compared to couples in same-race marriages—even when grandchildren were involved.

“This was especially true for white mothers of biracial children,” Bratter says. “This suggests that extended family members, on average, are not as involved in the lives of interracial couples.” And the stresses these couples face are compounded among those with low socioeconomic status, she says.

Bratter and Campbell say that the research reviewed in their study does not support the assumption that interracial relationships reduce racism.

So what can be done to improve the relationships between interracial couples and their families? The scholars say more research must take place but designing interventions that help build support within and beyond families is a good place to start.

“We hope future research will address how to foster more open conversation and dialogue among extended family members,” Bratter says. “This really has the potential to expand support and could go a long way in addressing the underlying vulnerability faced by many multiracial families.”

Source: Rice University