Researchers have discovered the molecule responsible for guiding T cells toward tumors, setting the stage for improvements to immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy, particularly CAR T-Cell treatment for cancer, is extending the lives of many patients. But sometimes the therapy randomly migrates to places it shouldn’t go, tucking into the lungs or other noncancerous tissue and causing toxic side effects.

The next step in the project is to find a drug that can manipulate the key T-cell protein, ST3GAL1, says Minsoo Kim, corresponding author of an article in Nature Immunology that describes the research. If the investigation evolves as planned, such a drug could be added to the CAR T-cell regimen to ensure that T cells hit their targets, Kim says.

His lab is collaborating on screening for drugs that will accomplish that feat, while also minimizing the risk of life-threatening side effects.

“You can create very powerful treatments,” says Kim, co-leader of Wilmot Cancer Institute’s Cancer Microenvironment research program at the University of Rochester, “but if they can’t get to their targets or they go to the wrong place, it does not provide the outcome you intended.”

Enlisting a patient’s own immune system to wipe out cancer has emerged as one of the most promising advances in cancer care.

CAR T-cell therapy involves extracting a patient’s own T cells, a type of white blood cell, and re-engineering them outside of the body to recognize cancer. Once the reprogrammed cells are infused back into the patient, they act as a “living drug,” searching for proteins on cancer cells for assault. In 2016, Wilmot was selected as one of the few national sites to begin clinical trials for this procedure, and later, upon FDA approval, became one of the first cancer centers in the United States to offer CAR T-cell treatment for eligible patients.

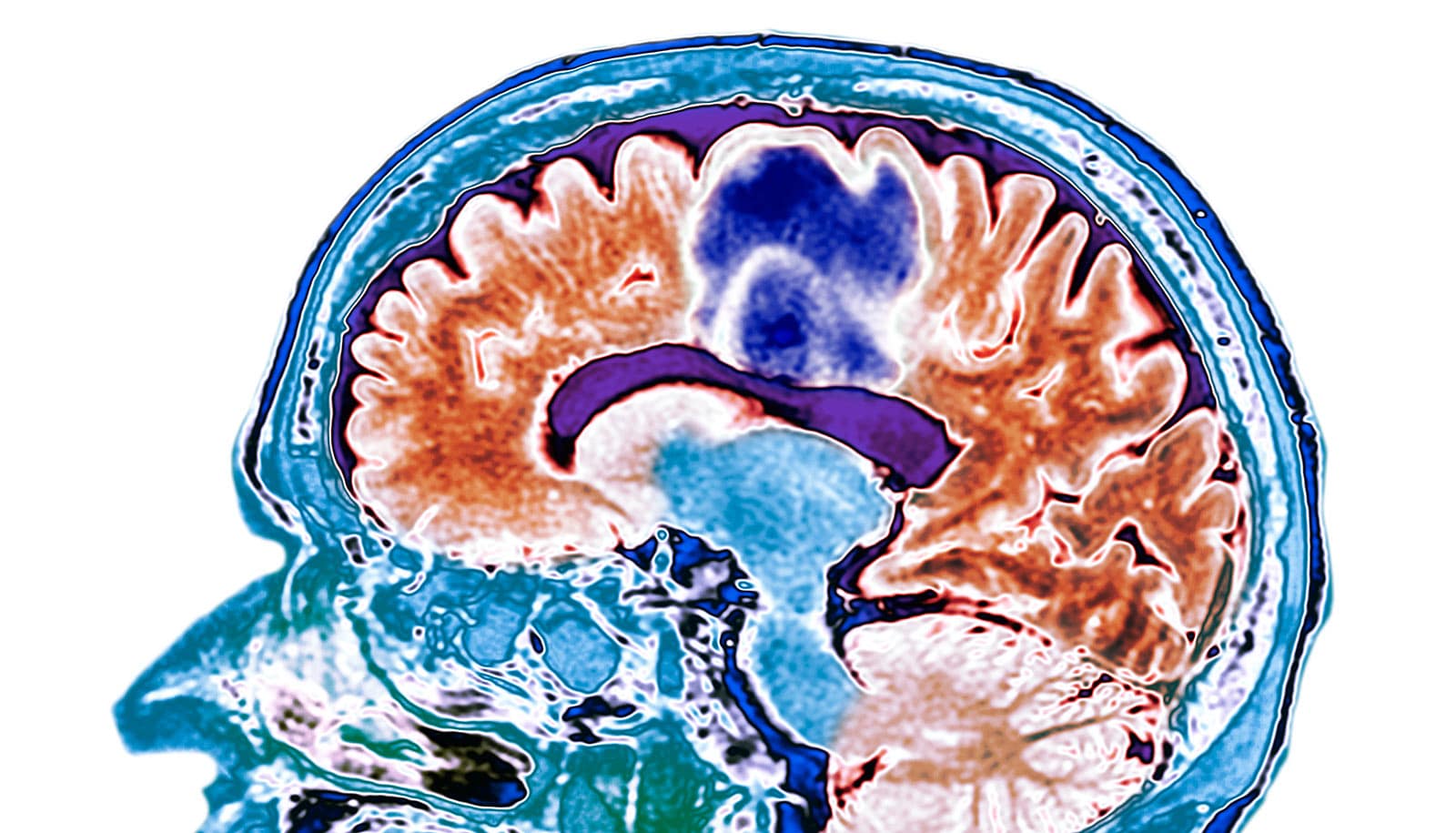

CAR T-cell therapy is only approved to treat blood cancers, including some forms of lymphoma, leukemia, and multiple myeloma, according to the National Cancer Institute. It’s easier for the altered T cells to drift toward cancer hot spots in the bloodstream, Kim explains—but finding their way to solid tumors such as breast, lung, brain cancer, or melanoma is a completely different story. The T cells have to work harder to migrate through tissues and organs and identify a solid tumor.

In fact, clinical trials testing this treatment in solid tumors have not been as favorable, Kim says.

Wilmot research suggests that something occurs during the re-engineering of T cells that blunts their homing properties.

In 2019, Kim and Wilmot colleagues Patrick Reagan and Richard Waugh received a National Institutes of Health grant to investigate the downside of CAR T-cell treatment, specifically what takes place when T cells sequester in noncancerous tissues.

Their discovery of the crucial migration-control gene that expresses ST3GAL1 came about through “unbiased genomic screening,” a more effective way to study the problem, Kim says. Investigators used a cutting-edge CRISPR technique to edit thousands of genes expressed in T cells, and then tested the migration-control abilities of those genes, one-by-one over the course of nearly four years, in mouse models.

Funding primarily came from the NIH, as well as from Wilmot.

Source: University of Rochester