A new book argues that the Constitution’s wording has had a long-term impact on migration to the country.

Over the past year, US cities and states have taken action against migrants in ways that some pundits have called “un-American”—from legislation that would ban those who are citizens of certain countries from purchasing property in Texas to buying bus tickets and chartering planes to move migrants to other locations.

“The idea of states’ rights, despite its genealogy… is not inherently reactionary. It depends on who uses it and for what purpose.”

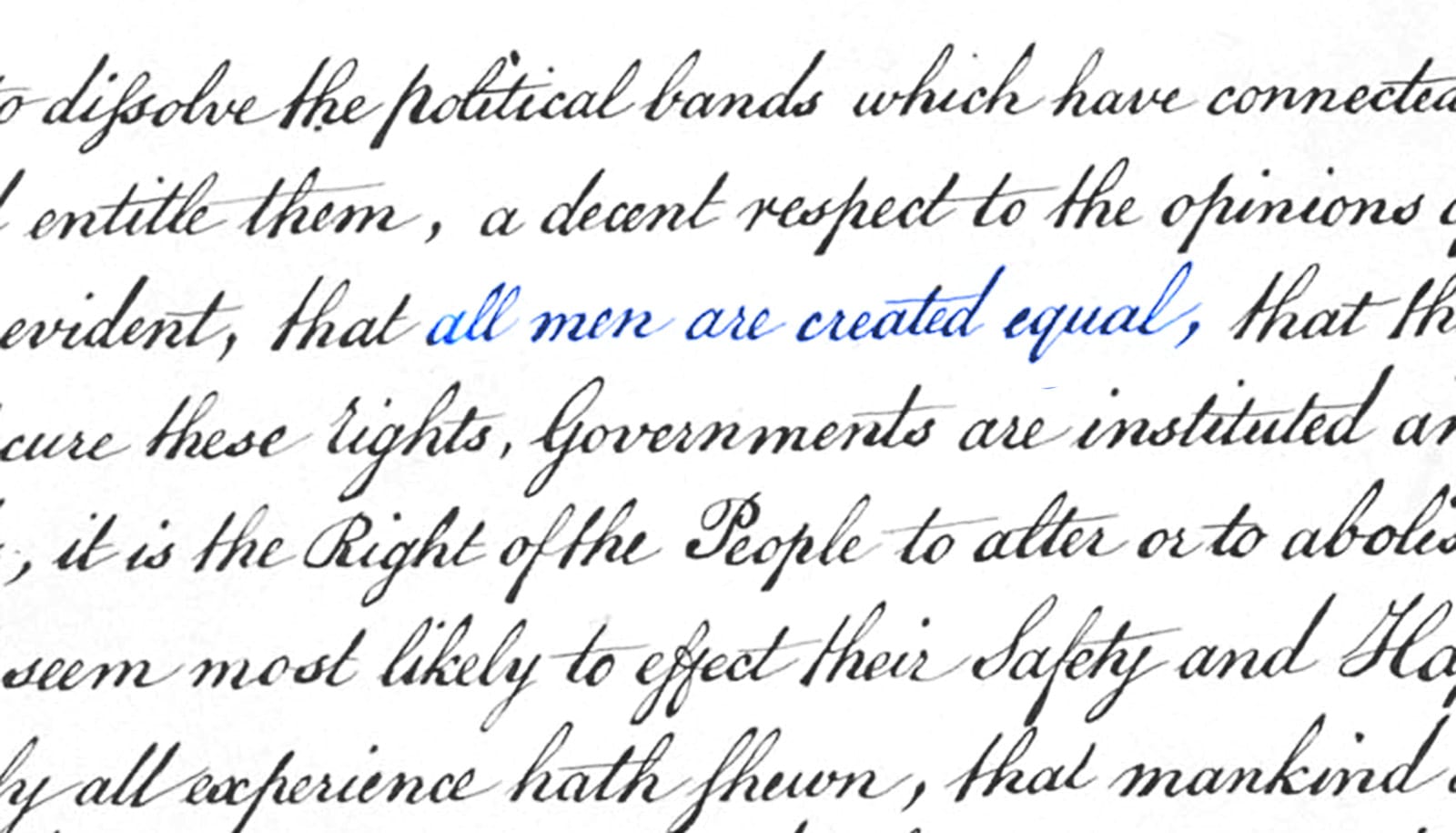

But as New York University historian Kevin Kenny notes, the foundation for these maneuvers, which have been both criticized as “dehumanizing” and defended as necessary, was, in fact, made in America—back in the 18th and 19th centuries, with the adoption of the Constitution and its later amendments. And, like many of today’s thorniest political issues, the debate about immigration policy has connections to the nation’s initial commitment to the institution of slavery.

“No state can determine, anymore, who can enter the United States and who can be excluded,” explains Kenny, author of the newly released The Problem of Immigration in a Slaveholding Republic (Oxford University Press, 2023) and director of the university’s Glucksman Ireland House. “But states, towns, and cities can adopt policies regulating the lives of immigrants after they get here. This question of what I call ‘immigration federalism,’ with power divided between the center and the localities, is still playing out today.”

With immigration and migration becoming increasingly significant as both a domestic and global matter—nearly 900 million people worldwide sought to migrate in 2021, according to a Gallup poll—Kenny speaks here about what the Constitution says on these matters and how a “twisted reading” of one of its amendments had been used to exclude the entry of some to this country:

“Strangely for a country that attracted so many immigrants, the Constitution says nothing about their admission, exclusion, or expulsion,” you write in The Problem of Immigration in a Slaveholding Republic. Why was this not addressed in any meaningful way until after the Civil War?

Now, it’s notoriously difficult for us to understand what was in the mind of the framers of the Constitution. You could say that immigration, as we understand it—as a mass phenomenon—really isn’t the issue on their mind, because everybody in the new United States was either a foreigner or a descendant of a foreigner, with the exception, obviously, of the native indigenous population.

But there was the slavery question. The Constitution does mention one form of migration, and that’s the migration of enslaved people. The Constitution has a provision that the external slave trade—the importation of enslaved people into the United States—cannot be prohibited for 20 years. That means the Constitution is recognizing and protecting the institution of slavery.

So when authority over immigration becomes a constitutional question from the 1820s onwards, there’s a problem because, on the one hand, Congress does have power under what’s called the Commerce Clause to regulate the interaction of the United States with foreign nations and to regulate movement between the states. So there’s an argument that maybe the Constitution indirectly provides authority over immigration.

But this is a federal system of government, one in which the states reserve very important powers. And one of the most important powers that the states reserve is the power to control their own borders. In the context of slavery, this becomes critically important because if Congress were to exert its power over immigration to control the arrival of foreigners, it thereby has power over mobility that could be used in other ways, including to regulate the movement of free Black people between the states.

The presence of free Black people is a threat to the slave states because the “logic” of slavery is that the normal condition of a person of African descent is slavery. The states in the South then rigorously control the movement of free Black people. Even more, the interstate slave trade remains intact.

Could Congress theoretically have used its commerce power to regulate the interstate slave trade?

Well, abolitionists said yes and Southerners said no. So you arrived at a problem—almost a contradiction in the Constitution. And it’s not one that can be resolved before the Civil War. If Congress had exerted this power during this period, you probably would have had secession and civil war sooner.

The prohibition of slavery, under the 13th Amendment, was subsequently used to enact racist immigration laws, notably against Chinese laborers. How was this “twisted reading”—as you describe it—of the amendment justified at the time?

The Civil War clears a path towards a national immigration policy because it results in the abolition of slavery—once you remove slavery from the picture, the political and constitutional obstacles to a national immigration policy are removed. That doesn’t mean, however, that Congress would have acted to restrict immigration a generation earlier in the absence of slavery, because at that time most of the immigrants were European. Even the Irish, who were the most despised of the immigrants in the antebellum period, did not face demands for numerical restriction. They faced prejudice. They faced discrimination. But the American economy needed their labor.

The abolition of slavery then changes things and a national policy emerges in the 1860s and 1870s. And the first targets are the Chinese—through what I call the twisted reading of the 13th Amendment that leads to an anti-slavery argument in favor of the exclusion of the Chinese.

The Chinese started arriving in the American West at the end of the 1840s, and they encountered intense hostility. Immigration restrictionists referred to them as “coolies”—a term that described an exploited and degraded contract worker whose conditions supposedly differed very little from slavery.

The problem with that is “the coolie” is not a social reality. It’s an ideological construct. Some Chinese laborers came to the United States under pretty harsh conditions, to be sure, but most, like other immigrants, came in under a variety of arrangements. Some had contracts like indentured servants, and in the 18th century, some were wage workers. Some were entrepreneurs. Some were self-employed.

At this time, there’s a racial backlash against the Chinese in the context of civil war and reconstruction. Notably, the passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868 extends rights of due process and equal protection to all residents, including Chinese immigrants. Chinese immigrants cannot become naturalized citizens at this time, but their children under the 14th Amendment are automatic citizens by birthright.

So restrictionists in the American West find this very threatening, and they craft a devious and unfortunately highly persuasive argument as follows: The 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865, prohibited slavery in the United States. So slavery is illegal in the United States, and that leads to the twisted syllogism: Slavery is illegal in the United States. Chinese laborers are slaves as coolies. Therefore, the Chinese must be excluded.

You write in the book that the term “states’ rights”—cited by many as the Confederacy’s only cause in fighting the Civil War—has historically been associated with “racism, in the form of slavery and Jim Crow.” However, you also write that prior to the Civil War, “states enacted personal liberty laws to resist fugitive slave laws” and add that in recent years US cities and states have “refused to act as agents of federal immigration enforcement and play a vital role in protecting immigrants’ rights.”

It goes without saying that I am no evangelist for states’ rights. Yet, researching and drafting my book in the midst of a virulently anti-immigrant Trump administration, I was struck by the important role that cities and states can play in protecting immigrants and integrating them into society. In fact, federal policies would be more effective in this respect. But in their absence, or with the federal government taking an actively anti-immigrant position, states and cities can play a progressive role.

In other words, the idea of states’ rights, despite its genealogy—slavery and Jim Crow—and some of its current manifestations—on guns, gender, and sexuality—is not inherently reactionary. It depends on who uses it and for what purpose.

The treatment of immigrants today has parallels in the antebellum period. In the 21st century, some states are hostile to immigrants, cooperate with federal agencies like ICE, and want the federal government to do more. Other states welcome immigrants and, although they cannot violate federal laws, provide sanctuary and refuse to act as agents of federal law enforcement.

All of this reminded me of how Northern states asserted their sovereignty to pass personal liberty laws to protect runaway slaves in the antebellum era, while Southern states—otherwise vocal in their defense of states’ rights—called on the federal government to protect their interests with a new Fugitive Slave Act, which was passed in 1850.

Are there other terms whose meanings have historically been associated with a particular ideology but, in fact, have a broader significance?

One that occurs to me is this notion of “freedom.” One conception of American freedom, perhaps the dominant one, is freedom from government. But American history contains rival conceptions of freedom from—from want and fear, for example, in FDR’s formulation—as well freedom to: the freedom to vote or the freedom to be free from enslavement, which are not simply the obverse of government constraints.

All of this, however, still leaves the question of why certain terms persist in one dominant sense, even if there were other rival meanings, or why meanings changed over time, or why current meanings are out of sync with present realities.

For me these are fundamentally historical questions, and as a historian I would approach them empirically, searching for evidence in order to interpret change over time, rather than starting with an explanatory model.

Source: NYU