New research delves into the rise of true-crime podcasts to investigate their impact on juries and trials.

True-crime dramas and podcasts have exploded in popularity over the past several years, tapping into the American fascination with crime stories. They might also be changing the way juries act in courtroom trials. That’s the subject of a law review article coauthored by Kat Albrecht, assistant professor of criminology in Georgia State University’s Andrew Young School of Policy Studies.

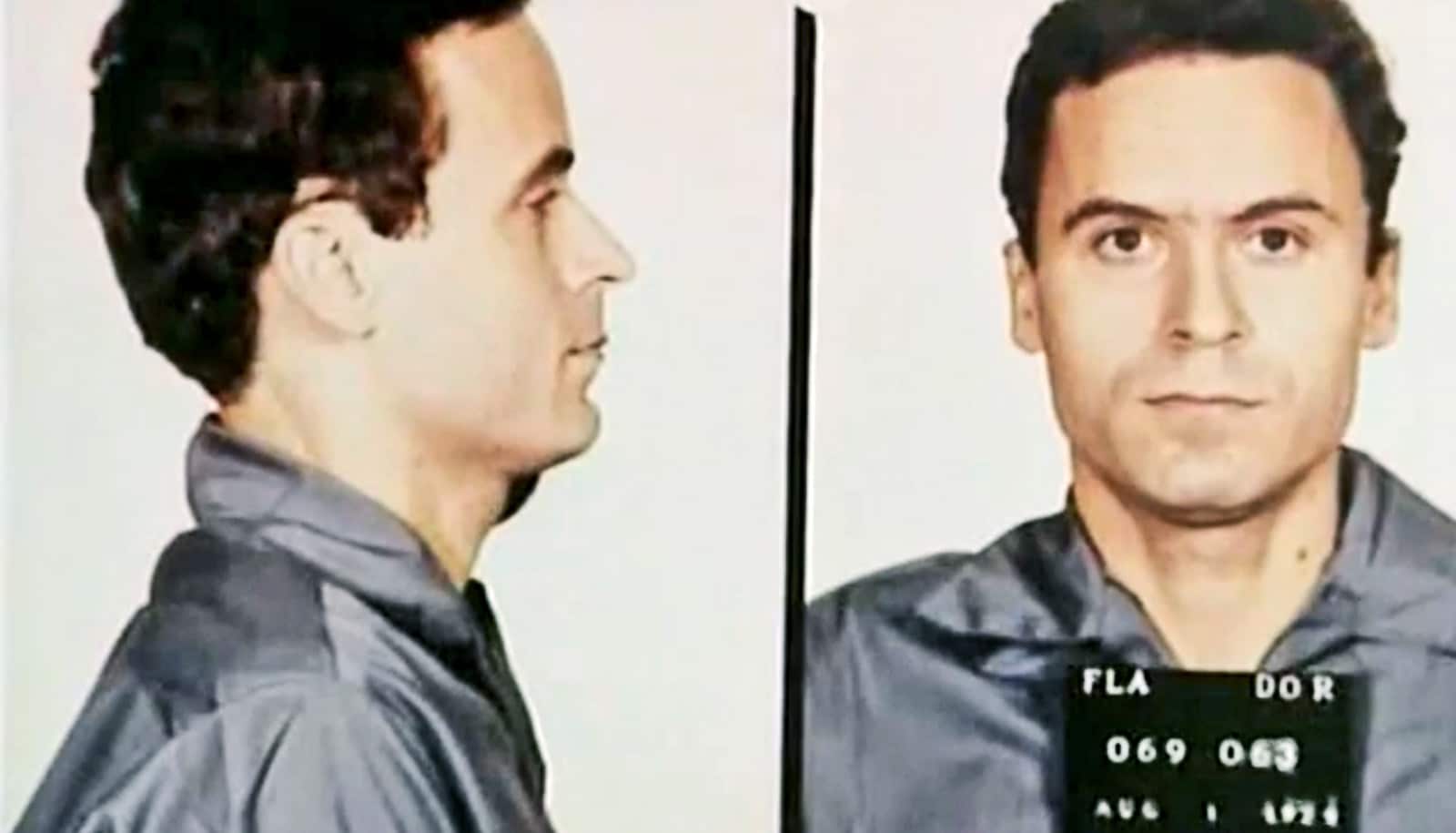

The research focuses on a phenomenon known as “The Serial Effect,” named for the wildly popular true-crime podcast that followed the murder trial of Adnan Sayed. More than 40 million listeners tuned in.

“We wanted to look at what listening to a true-crime podcast would mean for how people understand the legal system,” says Albrecht. “These podcasts say they are giving you a look behind the curtain at what happens in courts. So, by being heralded as investigatory journalism, they can actually influence cultural perceptions of criminal cases.”

The study, published in the New Mexico Law Review, looks at two popular podcasts, Serial and In the Dark, to gauge their impact on the juries’ perception of criminal procedure, evidence, and—most importantly—the idea of a defendant’s guilt or innocence.

The CSI Effect

The phenomenon known as the Serial Effect piggybacks off of another theory known as the “CSI Effect” which suggests entertainment shows like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation or Law & Order have a quantifiable impact on juries. The effects can lead to jurors holding unrealistic expectations of forensic evidence and affect their decisions.

“We’ve heard about the CSI Effect,” Albrecht explains. “But what does it mean when you add that layer of the media telling you it’s true? You may expect if the CSI Effect changes how people make decisions, then the Serial Effect could have greater impact than something that’s telling you it’s fiction.”

Albrecht says she became interested in the topic while she was finishing law school at Northwestern University. Working with coauthor Kaitlyn Filip, the pair set out to create a legal argument, then test it. Working together, they looked at the phenomenon from a legal standpoint and a sociological perspective.

True crime podcasts

“We plotted the trends and data about these podcasts, to try to see if we could hypothesize how the podcast itself contributed to the notoriety of the case, and its ultimate legal resolution,” says Albrecht.

“We concluded that podcasts are distinctively different from other forms of true-crime media, but they’re also different from each other.”

In the study, both of the cases had significant changes in their actual progress through the legal system following the podcasts and both defendants are now free. In the case of “Serial‘s” Adnan Syed, his case is still winding its way through the legal system. His murder conviction was initially overturned after he spent 22 years in prison, only to have the case against him re-instated. In the Curtis Flowers case—featured on In the Dark—the district attorney who tried Flowers six times for murder eventually declined to prosecute after repeated issues related to racial discrimination.

What’s true? Does it matter?

In a 2022 poll, half of Americans says they enjoy the genre of true crime, including 13% who call it their favorite genre. But Albrecht says it’s getting harder to tell what actually constitutes “true” crime.

“What’s really interesting is, at some level, it doesn’t matter what’s true,” she says.

“The lines of true crime are getting increasingly blurry. Is it entertainment? Or is it factual knowledge being delivered to the audience?”

The method of how evidence is delivered is of crucial importance whether you’re trying to sway a jury or keep an audience captivated.

“Some of these sorts of things you might hear in a podcast, you won’t hear in court, like speculation, or whether the defendant is a good person. Those things are not materially relevant to the evidentiary questions about a case,” says Albrecht. “But it’s really relevant in the world of the podcast, to make the story meaningful. So, it’s interesting to what extent that matters in the public perception of what criminal justice is, versus how it actually ends up resolved in a trial.”

There are some researchers who argue that the CSI Effect has not been proven to exist with juries, but, in certain cases, just the idea that it could exist has had real-life impact. In a case tried in Maricopa County, Arizona, prosecutors believed the CSI Effect was causing jurors to be out of touch with reality regarding the importance of forensic evidence—so much so, that they adjusted the way they conducted their prosecution and court business.

“If the people making decisions in court think it’s real,” says Albrecht, “then for all intents and purposes, it’s still having an effect.”

More work to do

Albrecht says she’d like to see more research on how perceptions and knowledge from true-crime podcasts are actually making it into courtrooms and to juries, and to people who work in the courts.

She is conducting a new analysis with Georgia State graduate student Sierra Bell that focuses on the role of expertise in legitimizing different crime and entertainment content. They’re looking at the so-called “experts” featured in true-crime shows to gauge the veracity of the claims being made to ascertain if they’re supported by the body of scientific literature.

Albrecht says as more Americans are engaged in and learning about the justice system, it should be a net positive, but she also warns that many people aren’t getting a realistic view of what happens in the majority of cases.

“There are good things about people understanding court procedures, or unfairness in the justice system,” says Albrecht. “But we also should be cautious that we’re only seeing the most interesting parts of the justice system. Most court appearances are not the trial of the century.”

Source: Georgia State University