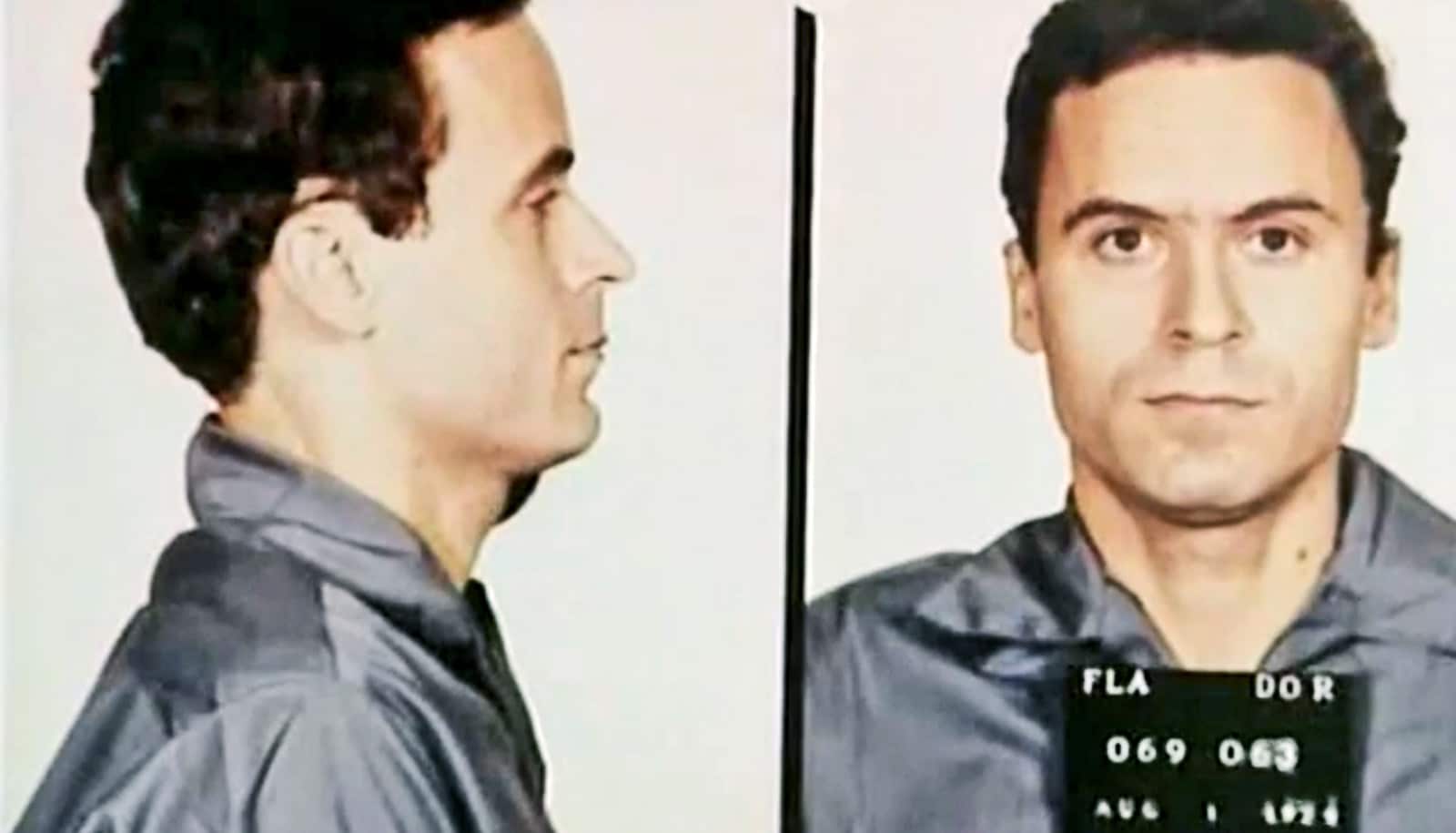

A criminologist’s new book argues that Ted Bundy’s criminal career was longer and deadlier than the official record from 1974 to 1978.

In his new book, Matt DeLisi, a world-renowned criminologist at Iowa State University, lays out evidence that Ted Bundy’s criminal career was far lengthier and deadlier than the official record from 1974 to 1978.

In Ted Bundy and the Unsolved Murder Epidemic: The Dark Figure of Crime (Palgrave MacMillan, 2023), Matt DeLisi of Iowa State University underscores how most crime is never known to law enforcement. The book also emphasizes that a small percentage of individuals in society commit a much larger share of violent crime. With an estimated 250,000 to 350,000 unsolved homicide cases in the US, DeLisi offers solutions for clearing the backlog and bringing justice to victims and their families.

DeLisi says he “learned about Ted Bundy when America did.” As a young boy, DeLisi watched nightly news coverage of Bundy’s crimes, jail escapes, and ultimate capture. He was in high school during Bundy’s execution in 1989 and his academic interests coincided with the burgeoning true crime genre. With 25 years now as a practitioner, researcher, and consultant on violent criminals, DeLisi weaves his expertise with the accounts of people who knew Bundy intimately.

“Bundy drops a lot of clues that there were way more murders than the official victim account of around 30 young women and girls. And the pacing and confidence with which he’s killing between 1974 and 1978 indicates there’s no way he could have just started. To me, it really reflects someone who had been doing this for years,” says DeLisi.

Throughout the book, DeLisi builds his argument that Bundy’s murder count was likely 100 or more and that his first killing was in adolescence. Stories from people who knew Bundy as a child indicate early signs of his psychopathology. As a three-year-old, Bundy placed knives around his sleeping aunt and watched her until she awoke. He pulled apart mice in the woods, tried to drown others while swimming and boating, and stole constantly throughout his life.

DeLisi writes, “He wasn’t some normal, law-abiding citizen who just snapped and went on a murder spree.” In prison, Bundy was diagnosed as a psychopath, and he showed clear signs of sexual sadism among other conditions. Bundy had “no sense of remorse, guilt, embarrassment, or shame for his violent transgressions” and enjoyed hurting others. DeLisi says these disorders—especially the combination—are extremely rare in the general population, but they’re shared by other infamous serial killers of the era, including Samuel Little and Rodney Alcala.

One of the chapters, “The Open Road,” explores why unsolved murders increased nearly 80% between 1960 and the early 21st century. The rapid development of highways and interstates made it easier for criminal offenders to find victims and evade detection. Hitchhiking was common, and parents were less concerned with monitoring and surveillance. Without cellphones and GPS, it was much harder to know if someone was missing.

The criminal justice system also struggled with sharing information about wanted subjects and missing persons between jurisdictions and with the public.

“A lot of bordering agencies didn’t know they had murders happening in the other jurisdiction, but there were also petty professional issues with some people not wanting another agency to get involved. Offenders like Ted Bundy knew how to exploit that,” says DeLisi.

Gas receipts in Bundy’s car showed he often drove hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles, even when he was the most wanted man in America. DeLisi writes “for the entirety of Ted Bundy’s offending career, the criminal justice system was woefully underequipped to locate, arrest, detain, or frankly, to even identify him.”

The ability to use DNA as evidence would come years after his crime spree, as would the development of the Automated Fingerprint Identification System and National Missing and Unidentified Persons System.

DeLisi says the ability to share information and link multiple crimes to an offender is exponentially better and faster today. One of the most important advancements in forensic science technology was the centralized database for DNA samples (Combined DNA Index System or CODIS), which was implemented in 1998. With increases in federal funding over the last two decades, local and state law enforcement agencies have used CODIS to link multiple crimes and solve cases.

A US Supreme Court ruling in 2013 “upheld that the collection of DNA evidence via a buccal or cheek swab is consistent with other evidence gathering procedures during the booking process, such as fingerprinting,” writes DeLisi. But he points out that only 30 states collect a DNA sample when someone is arrested. Other states require probable cause hearings before the sample is either collected or analyzed.

DeLisi says these are “unnecessary judicial impediments.” He adds that some law enforcement agencies are reluctant to submit forensic evidence due to backlogs or insufficient funding for laboratory analysis.

Directing more resources to these agencies and requiring DNA samples at the point of arrest is one of the best ways to catch the worst offenders, says DeLisi. Other innovations in forensic science, like ground penetrating radar, could help find bodies in clandestine burial sites. He says there’s growing awareness around Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, but the issue of unsolved homicides is still off the radar for many people in the US.

“We can and should do more,” says DeLisi. “I’ve always had a deep-seated appreciation for justice, especially for victims and for public safety, and to me, it’s reprehensible that people have these loved ones who have disappeared and don’t have any resolution.”

Currently, DeLisi is working on another book that focuses on DNA as forensic evidence in cold cases.

Source: Iowa State University