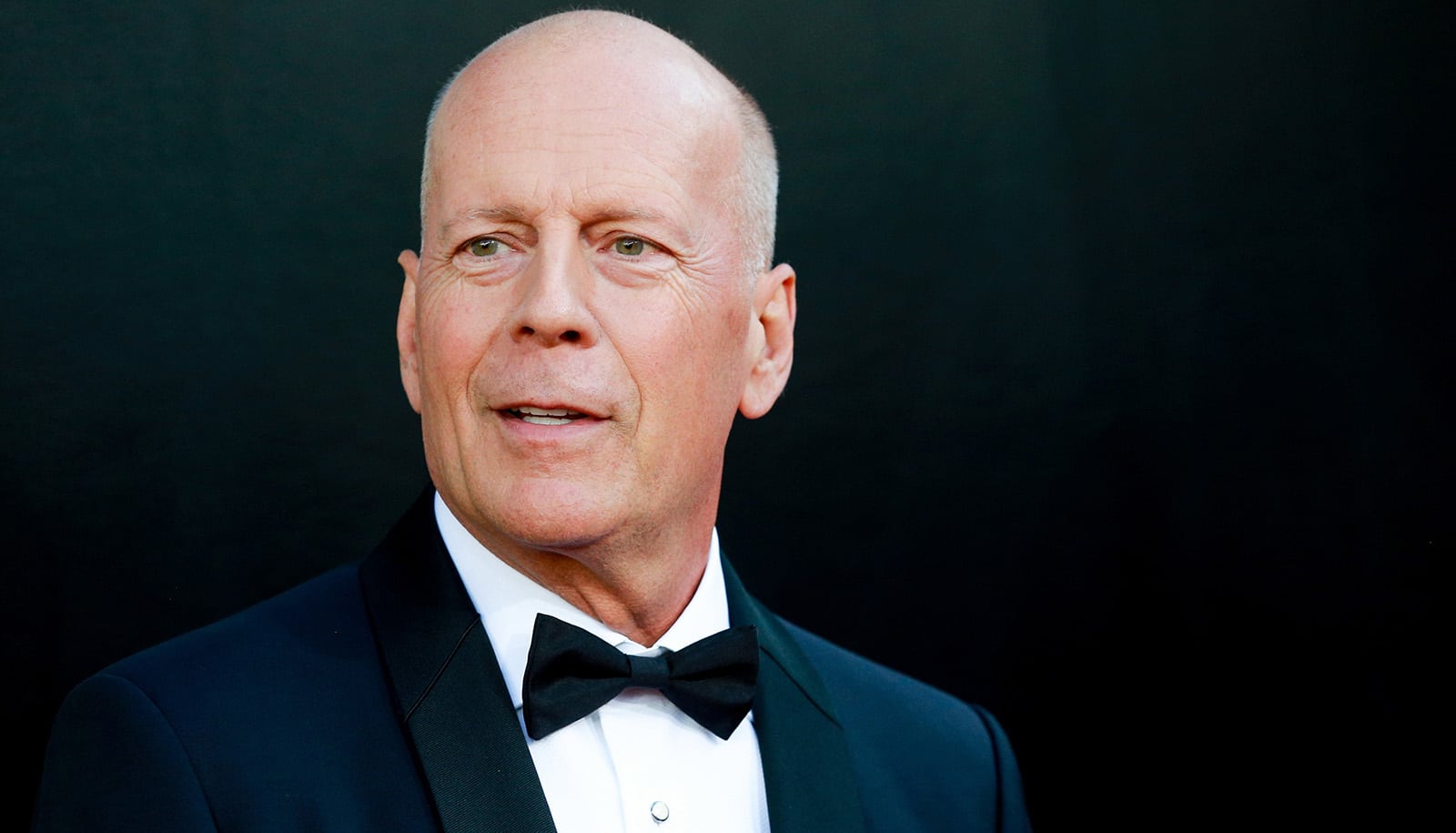

Less than a year after Bruce Willis was diagnosed with the neurological disorder aphasia, he now has a new diagnosis: frontotemporal dementia.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a group of disorders characterized by a progressive degeneration of nerve cells in the frontal lobe or the brain regions underneath the ears.

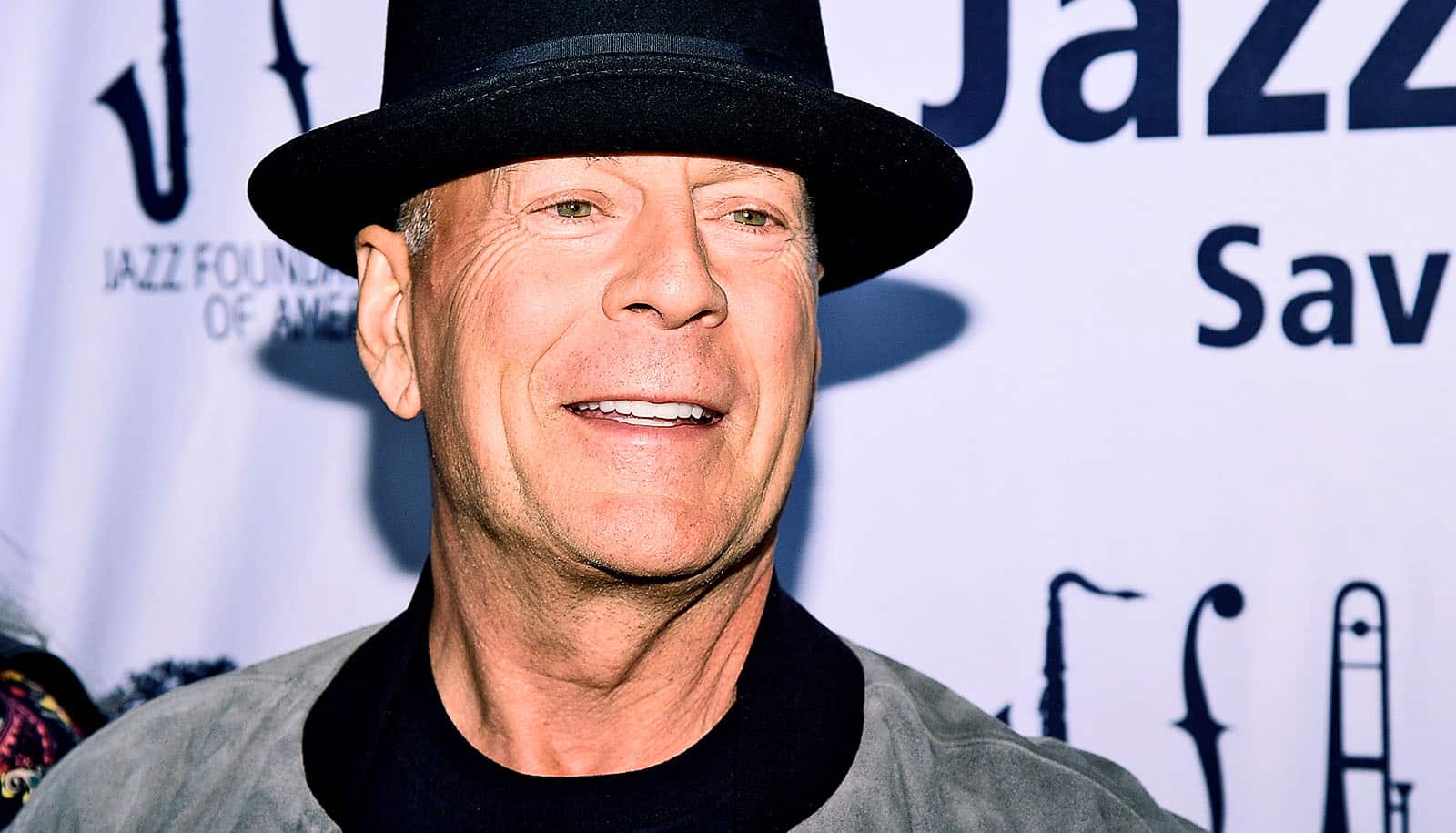

At the Boston University Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Andrew Budson, a cognitive and behavioral neurologist and cognitive neuroscientist, studies dementia, including FTD.

An expert on memory in people with Alzheimer’s disease and other brain disorders, his recent clinical and research work has focused on helping patients use music, pictures, and other strategies to enhance their memory—and reduce false memories.

Budson, a professor of neurology and chief of cognitive and behavioral neurology at the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, is also the author of popular books on memory, including Why We Forget and How To Remember Better: The Science Behind Memory (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Here, Budson talks about FTD—its causes, symptoms, progression, and what having the condition might mean for Willis—and how close researchers are to finding a cure:

Willis was diagnosed with aphasia last year. Were you surprised by the new announcement that he had frontotemporal dementia?

I knew Bruce Willis had primary progressive aphasia as soon as his family announced he had aphasia. If somebody’s aphasia was due to a stroke, a brain tumor, a car accident, or some other traumatic brain injury, you would just say they had a stroke, a car accident, or a brain tumor.

So, the fact that they said he has aphasia, I knew that it was primary progressive aphasia. Some of those people have Alzheimer’s and some have frontotemporal dementia, so it wasn’t surprising to me at all.

For many people, this is going to be the first time they’ve heard of frontotemporal dementia. What is it and what are some of the symptoms?

Frontotemporal dementia is an umbrella term for a family of disorders that all have the same underlying pathologies—that is, they all have this same family of abnormal proteins that you can see evidence of under the microscope. We now know that there’s more than a dozen different pathologies, more than a dozen different abnormal proteins that lead to this group of disorders called frontotemporal dementia.

There are two main syndromes that frontotemporal dementia manifest. One is what we call the behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, where the abnormal protein accumulates in the frontal lobes of the brain behind your forehead.

The frontal lobes are what help us to regulate our self-control, allow us to perform complicated activities, and put ourselves in other people’s shoes. When this protein accumulates in the frontal lobes, people lose their ability to regulate their self-control, they lose their ability for empathy and sympathy, they no longer take the initiative, and it’s very difficult for them to do complicated activities, like doing their bills or preparing a gourmet meal.

The other place that these pathologies can accumulate is in the temporal lobes and in a part of the frontal lobe just above the temporal lobe, a little bit further back. These are critical areas in the brain for language. When the pathologies accumulate there, individuals can have difficulty getting out an intelligible sentence. Sometimes the grammar can be distorted. The words themselves may be a little bit distorted. Another way that these language-based problems can manifest is that people actually lose the meaning of words, and these can be very common ordinary words, like ear or sweater or carrot.

Those language issues seem more in line with what we’ve heard about Willis’ condition.

What’s the connection between dementia and aphasia?

Aphasia simply means a lack of language. Primary progressive aphasia means that people have some progressive disorder of language and it’s the principal cause of their dementia, of their difficulty in being able to function due to their underlying brain disease.

When people with frontotemporal dementia have an accumulation of the pathologies in the temporal lobes, or a part of the frontal lobes just above the temporal lobes, it affects language, and when you have language problems that are severe enough that it’s impairing one’s ability to communicate, we call that aphasia.

How common is this type of dementia, how often do you see patients with frontotemporal dementia?

It’s probably somewhere between one-tenth to one-twentieth as common as Alzheimer’s. I might see a patient that has a problem like this once a month in my clinic, but that’s in contrast to patients with Alzheimer’s that I might see 10 or 20 times a month.

The other thing that’s unusual about these patients is when we think about dementia, we’re usually thinking about older adults, older than age 65, whereas approximately three-quarters of people with frontotemporal dementia are presenting younger than age 65. It certainly seems like that would also fit with Bruce Willis, who is 67 years old now, and probably the early symptoms started before he was 65.

Do we know what causes this type of dementia?

Yes and no. We know the likely pathologies that you can see under the microscope. In the variant of frontotemporal dementia that affects language and [where] people have trouble getting out intelligible sentences—that’s sometimes called the nonfluent/agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia—that particular type is usually caused by an accumulation of a protein called tau. There’s another common form of frontotemporal dementia affecting language in which the meaning of words is lost—the semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia—and that disorder usually has an underlying pathology of a different protein, TDP-43.

What we don’t have a good handle on is why do some people get these accumulations of proteins and other people not. We do know that in some people, approximately 40%, frontotemporal dementia runs in families, but that also means in 60% it doesn’t. We don’t really understand why.

We hear a lot about tau because of the work of the BU CTE Center. Is there any connection to that work or head impacts?

We can think of tau as a protein that can cause a lot of different disease pathologies. Tau is a normal protein that’s found in all neurons and all brain cells, and when it gets sort of changed by the disease, it ends up causing these problems and kills brain cells. That can be done in different ways and by different causes. Not only do we see tau in chronic traumatic encephalopathy due to repetitive head impacts, we also see tau in Alzheimer’s disease.

I’ve heard that frontotemporal dementia can leave some people in a nursing home within two years, but other people not for 20 years. Is there a typical progression of symptoms?

The pace is very different, in part because people are different and in part because the underlying pathology—the abnormal proteins—is different. In most people, it begins as either problems with behavior only or language only, but then, within a couple of years, those who have behavior problems also develop language problems and those who have problems with language first, develop problems with behavior.

There’s no cure, but as someone who does a lot of work supporting people with dementia and on memory, are there things that can be done to either help patients or to slow the progression?

One medication that has been useful for people who have behavior problems associated with frontotemporal dementia are the SSRI family of medicines—the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, what we often call the Prozac family of medications. These are definitely felt to improve some of the behavioral symptoms. For those who have language problems, we’ve also had good success early on, as have others, with speech therapy.

Most of the other work really comes with families learning to adjust to their loved ones’ difficulties. With my coauthor and fellow BU faculty member, Maureen O’Connor, we have a book to help families with frontotemporal dementia and other dementias, called Six Steps to Managing Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia: A Guide for Families (Oxford University Press, 2021). For example, if a loved one with frontotemporal dementia has trouble communicating what they want for dinner, you could show them an array of pictures on your cell phone of different entrée choices, and they can point to it. A lot of the supportive work is to help families learn to communicate with their loved one.

Could you share a quick overview of your research—are there any promising paths to prevention, diagnosis, or treatment?

We are working on using EEG electrodes to more easily be able to sort out who has different types of dementia, and we think that this is a promising strategy. There’s a lot of buzz around these new blood-based or PET scan biomarkers that are coming out, but they’re only for Alzheimer’s—they don’t help you diagnose frontotemporal dementia or other types of dementia—so we’re feeling positive about these EEG approaches.

The other things we’re working on in our laboratory are about helping people learn different strategies to just be able to function in day-to-day life—different strategies, different memory aids.

Can people get involved in your research?

Yes, we would absolutely welcome people to participate in our research. We are looking for people of any age, as long as they’re over 18, and they can have memory problems, frontotemporal dementia, or normal memory.

What message would you have for Willis’ family, or for other people reading this concerned about their own health or that of a loved one?

We finally have FDA approval of a new medication that looks like it can actually slow down Alzheimer’s disease. I think that just like with Alzheimer’s, we will in time be able to develop treatments that can slow frontotemporal dementia, as well. We’re just not there today—yet.

Source: Boston University