Anthropologist Fallou Ngom discovered Ajami, a modified Arabic script. Its existence shows that African people labeled illiterate for not writing in French were anything but.

When his father died in 1996, Ngom returned to Senegal from where he was teaching French and linguistics at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington. Ngom participated in the funeral services, spent time with his family, and collected some of his father’s belongings to bring on the daylong flight back with him.

A box of his father’s old papers—various to-do lists, dashed-off ideas, deeds, receipts, and other ephemera that collect throughout a life—lay dormant in a corner of Ngom’s office for nearly a decade before he opened it. He couldn’t have known it at the time, but waiting for Ngom inside this box was a scrap of paper that would alter the course of his life and the lives of countless others.

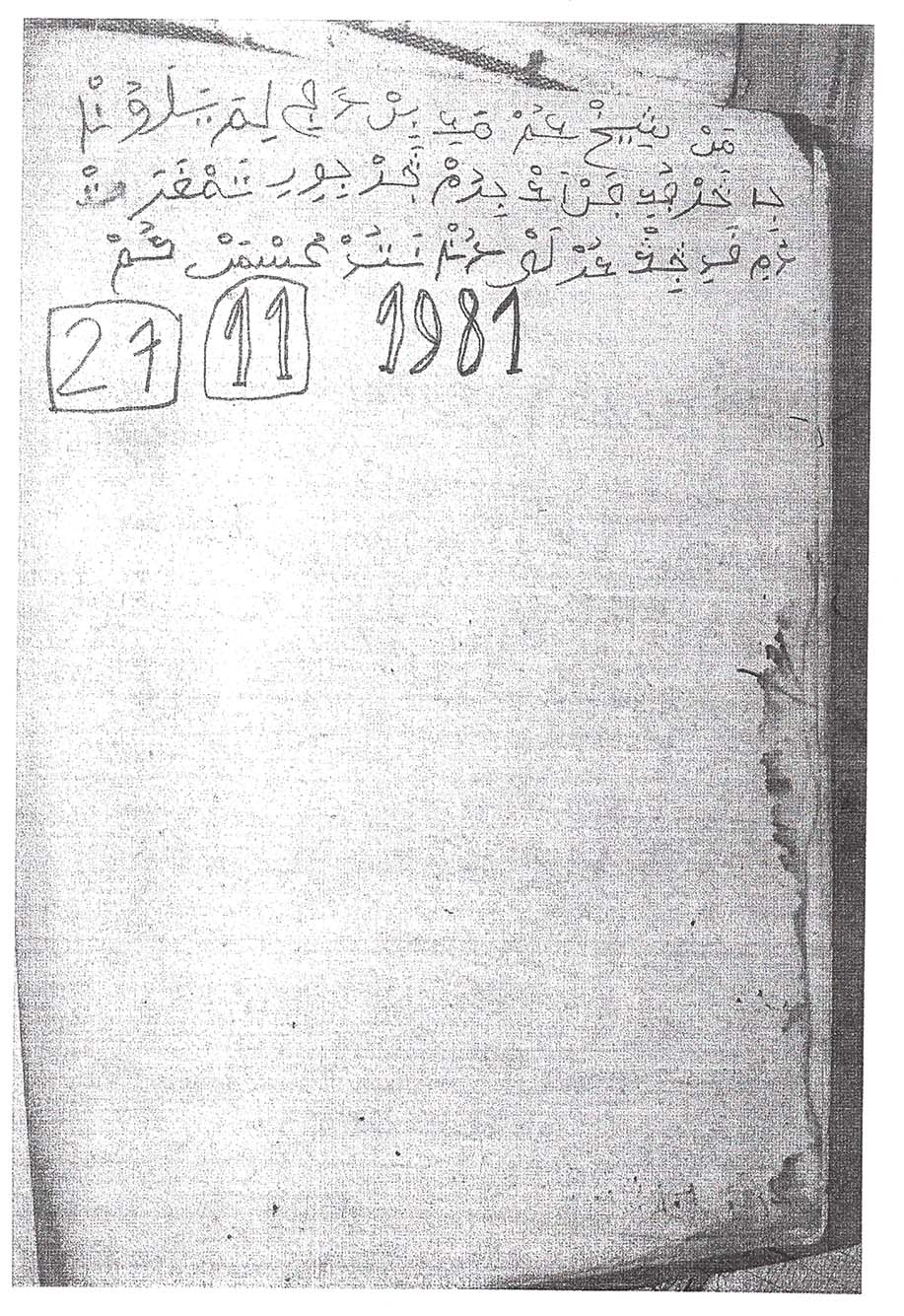

In 2004, when he dusted off the box and sat down to sift through these tokens of his father’s life, Ngom found something confounding: a note, scribbled in his father’s hand, about a debt he owed a local trader. The note was doubly surprising. First, Ngom had thought his father was illiterate—he didn’t read French, the official language of Senegal. But the note wasn’t in French, it was in a script that looked like Arabic, but sounded like Wolof, a regional West Atlantic language.

Ngom, who studied Arabic as a second language (the second of 12 languages that the scholar knows), was stunned. He asked his brother, still living in Senegal, to check with the neighbor to whom their father owed money. Sure enough, his brother reported, the trader had a record of the debt, too, in a similar Arabic-turned-Fula script.

“…not only were my dad and many people like him documenting their lives, many highly educated people were using Ajami to write poetry, literature, these kinds of things.”

“That’s when I realized: we’ve been told that these people are illiterate, and they’re absolutely not,” says Ngom, professor of anthropology at Boston University.

Ngom needed to know more. He applied for a postdoctoral fellowship in 2004 to travel to West Africa and dig into this surprising writing system.

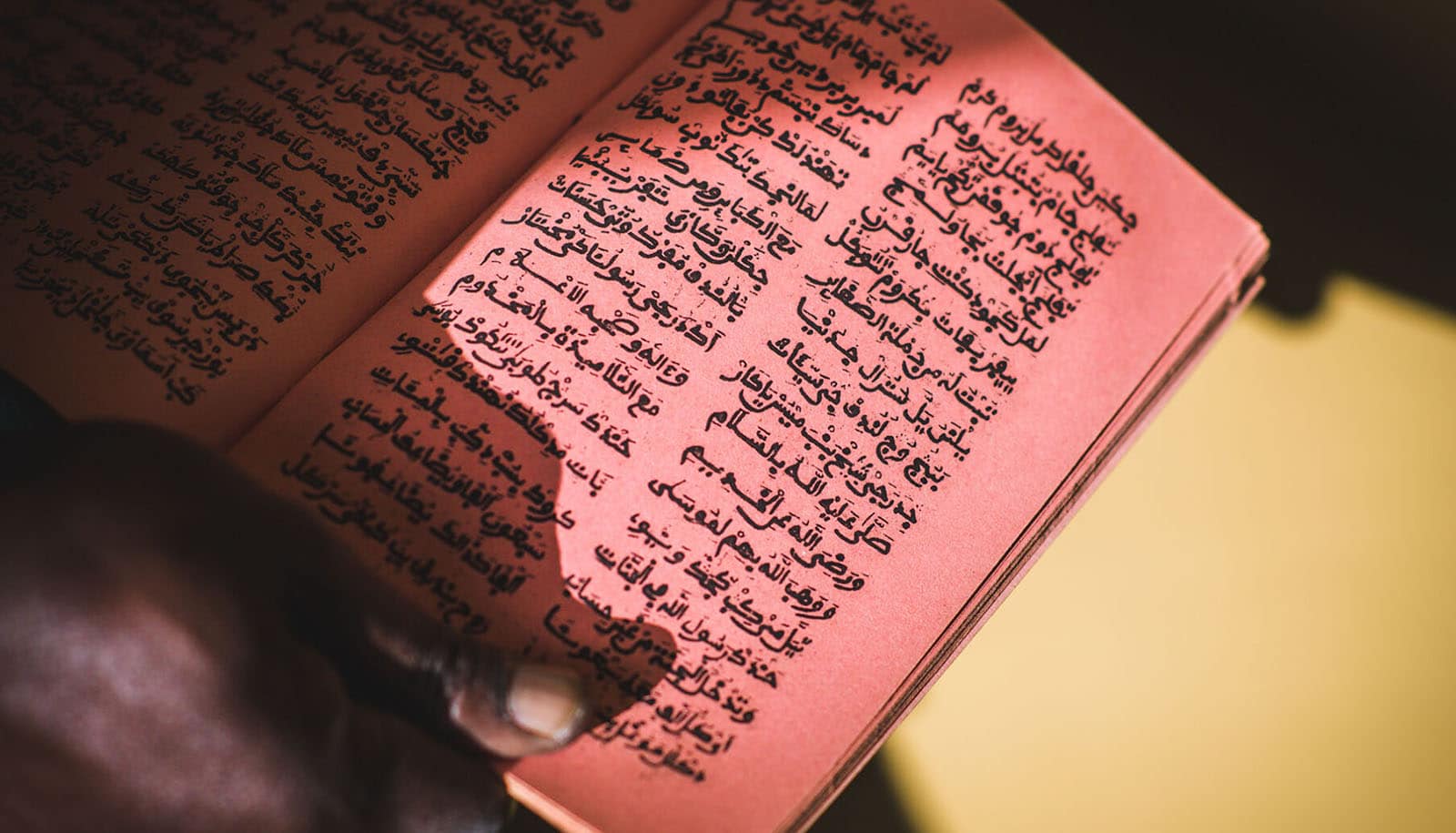

He found this modified Arabic script everywhere. Shopkeepers kept records with it and poets wrote sprawling verses in it. Ngom discovered religious texts, medical diagnoses, advertisements, love poems, business records, contracts, and writings on astrology, ethics, morality, history, and geography, all from people who were considered illiterate by the official governmental standards of their countries.

What Ngom realized—slowly, and then with a bang—is that his father’s notes were just the beginning. He had proof that a centuries-old writing system was still thriving in many African countries.

In the same way that the Roman alphabet has been adopted to write English, French, and Spanish languages, Ngom’s research revealed that people in Senegal, Guinea, Nigeria, and other parts of West Africa use a modified Arabic alphabet to write in a number of local languages: Wolof, Hausa, Fula, Mandinka, Swahili, Amharic, Tigrigna, and Berber among them.

It was an enormous discovery. This writing system, called Ajami, dispelled the false notion peddled by European colonialists that large swaths of communities in sub-Saharan Africa were illiterate, with no native written languages of their own.

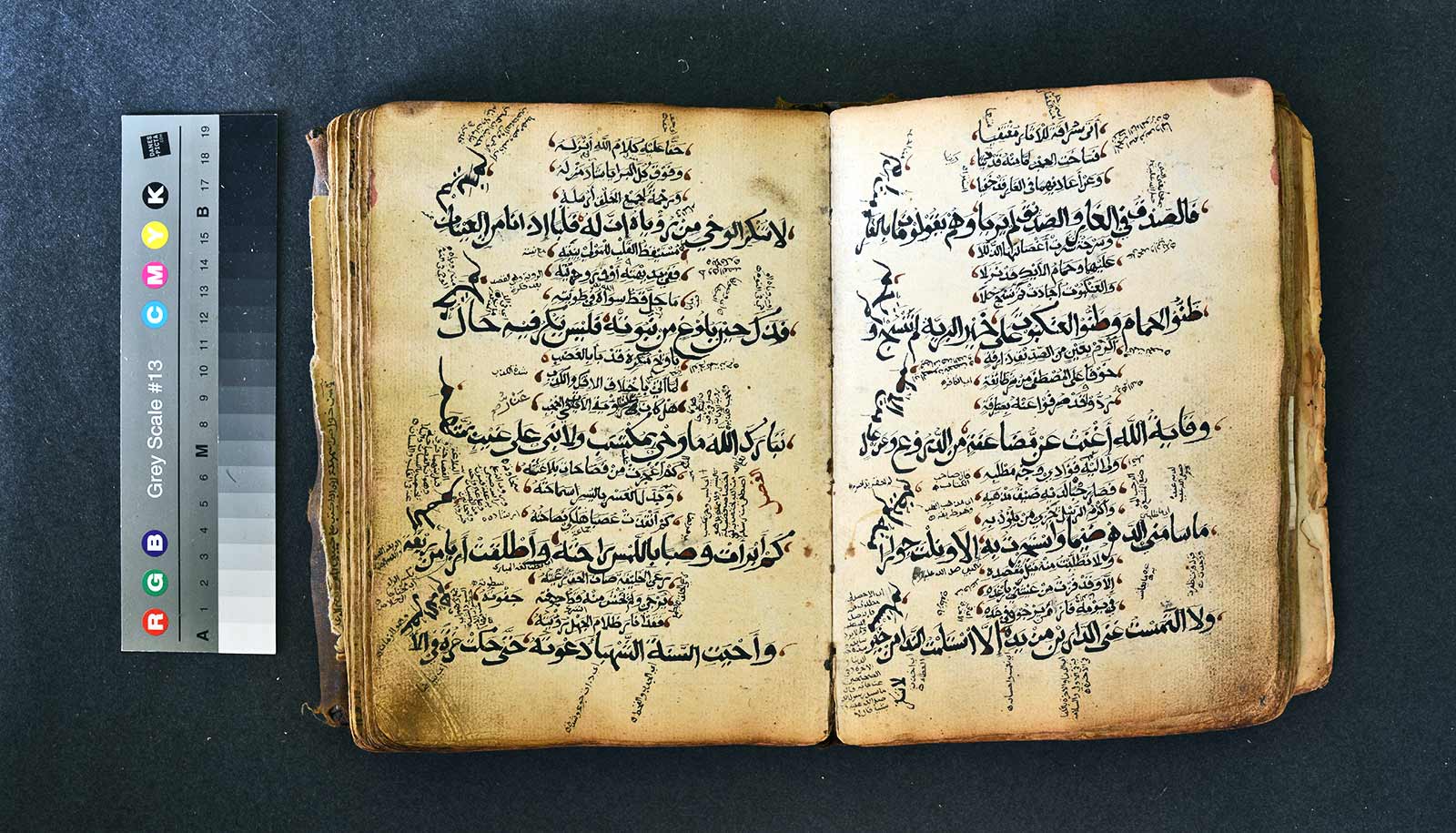

Some of the documents Ngom found on subsequent trips to the continent showed that their authors were code-switching throughout the text: writing in strict Arabic and in its modified Ajami form. Such writers were not just literate, but able to read and write in multiple languages.

“It was shocking,” says Ngom, who has helped build a vast digital library of Ajami texts. “It was so shocking to me when I realized how misguided I was as a result of my training, which is a French-based system. But not only were my dad and many people like him documenting their lives, many highly educated people were using Ajami to write poetry, literature, these kinds of things.”

People have been using the language to record the details of their daily lives since at least the 10th century, and still use it today. It’s a grassroots writing system, he says, one that’s not taught in schools. Even though he grew up in Senegal, Ngom didn’t know the writing system existed until he came across his father’s notes in 2004.

Resistance in Ajami

Ajami, from the Arabic word ʿAjamī, meaning “non-Arabic” or “foreign,” was created centuries ago by Islamic evangelists to spread the religion to African communities. Over generations, it was adopted by members of anticolonial nationalist resistance movements throughout the continent, as French and English colonists installed their own languages and customs.

Take the Mouride brotherhood in Senegal. By the end of the 19th century, French authorities in Senegal—who had expected the Sufi movement to fizzle out—were concerned about the group’s growing numbers and resistance to colonial rule. The Mouride brotherhood thrived, despite French attempts to quell the movement. Now, the group has a headquarters in Touba, a holy city for the order.

“The Mourides are one of the most studied groups in academia,” says Ngom, because of their unexpected resistance and staying power. “There is a lot of work on the Mouride, but none in the Mourides’ own voices, about why the movement didn’t fail as it was expected to. But it is actually in their Ajami text—they tell you why!

“They were trained through Ajami texts that were read and recited and chanted in rural villages. They were communicating messages that the French could not understand. And those messages were about resilience, self-sufficiency, and work ethic. That’s what made the movement succeed,” Ngom says.

African history by Africans

The documents that Ngom and other researchers—including Daivi Rodima-Taylor, project manager for the university’s Ajami Research Project and director of the African Studies Center’s Diaspora Studies Initiative—give light to African people’s view of their own history, a view that the prevailing narrative in postcolonial literature and history books has long obscured.

“To me, there’s justice in making these voices heard. For so long, they weren’t.”

“There have been ongoing discussions about African sources of knowledge, and this component has really never been taken seriously until now,” says Ngom. “So, for example, sources of African history have been European sources, primarily. But this is the first time we have a substantial number of documents produced by Africans dealing with those same issues on which their history has been written. And at BU, we are the leaders in this effort: we have documented over 30,000 pages from Africa.”

The university is also leading the charge to teach scholars how to read these documents, a massive (and massively important) undertaking. Under Ngom’s leadership, the university offers the only Ajami program in the United States.

“The first thing I did at BU was to make sure our students benefit from the training that allows them to read any script in this language,” Ngom says. “They’re trained to read any text: Roman script or in traditional Ajami script, and that ensures that their research is more inclusive of the voices of people whose countries they study.”

To augment translation of the texts, researchers enlisted volunteers from countries in West Africa—people who know and use the Ajami scripts every day.

“One of the important aspects of this work is revealed when our collaborators reflect about this participatory and collaborative endeavor,” says Rodima-Taylor, who is also a research associate at the university’s Pardee School of Global Studies. “We hear about how challenging it is to interpret some of those texts and, at the same time, how rewarding this process is.”

Thousands of scholars around the world—from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University in the US to Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto in Nigeria and Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia—have used this repository to spark new research.

Others, including one native Hausa person writing from Kano, Nigeria, simply thanked the researchers for helping him to understand the work of his late father, an Islamic scholar and calligrapher who worked tirelessly to preserve documents in the Hausa Ajami script.

For Ngom, this work is rewarding, if painful.

“To me, there’s justice in making these voices heard,” he says. “For so long, they weren’t. And my attention has shifted completely to making it happen.”

Source: Molly Callahan for Boston University