An experimental Alzheimer’s drug is effective in slowing cognitive decline for some patients, according to the findings of a new clinical trial.

The drug, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, may be the first significant treatment advance in decades.

The drug, called lecanemab, is a humanized monoclonal antibody manufactured by Biogen and Eisai and administered intravenously every two weeks. It targets beta amyloid, a toxic protein that accumulates to form plaques in the brain and is believed to be a significant driver of Alzheimer’s.

The international double-blind phase 3 clinical trial followed nearly 1,800 participants for 18 months. According to the study’s authors, the drug “resulted in moderately less decline on measures of cognition and function,” particularly in patients in the early stages of the disease with mild cognitive symptoms.

The study also showed that some patients experienced brain swelling, which has been observed in other experimental drugs that target amyloid beta.

The University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) Alzheimer’s Disease Care, Research and Education Program (AD-CARE), which is led by Anton Porsteinsson, has been involved in more than 200 clinical studies for Alzheimer’s disease since 1986 and served as a study site for both the phase 2 and 3 clinical trials of lecanemab.

Here, Porsteinsson talks about what the new findings mean for people with Alzheimer’s disease:

What were the results of the phase 3 clinical trial for lecanemab?

This is one of the largest clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease and was unique in that it had higher participation of historically underrepresented groups than in previous studies. It also allowed volunteers with more medical comorbidities to enter the study. Usually participant populations in studies like these are healthy, so this created a more representative sample of the Alzheimer’s population in the real world.

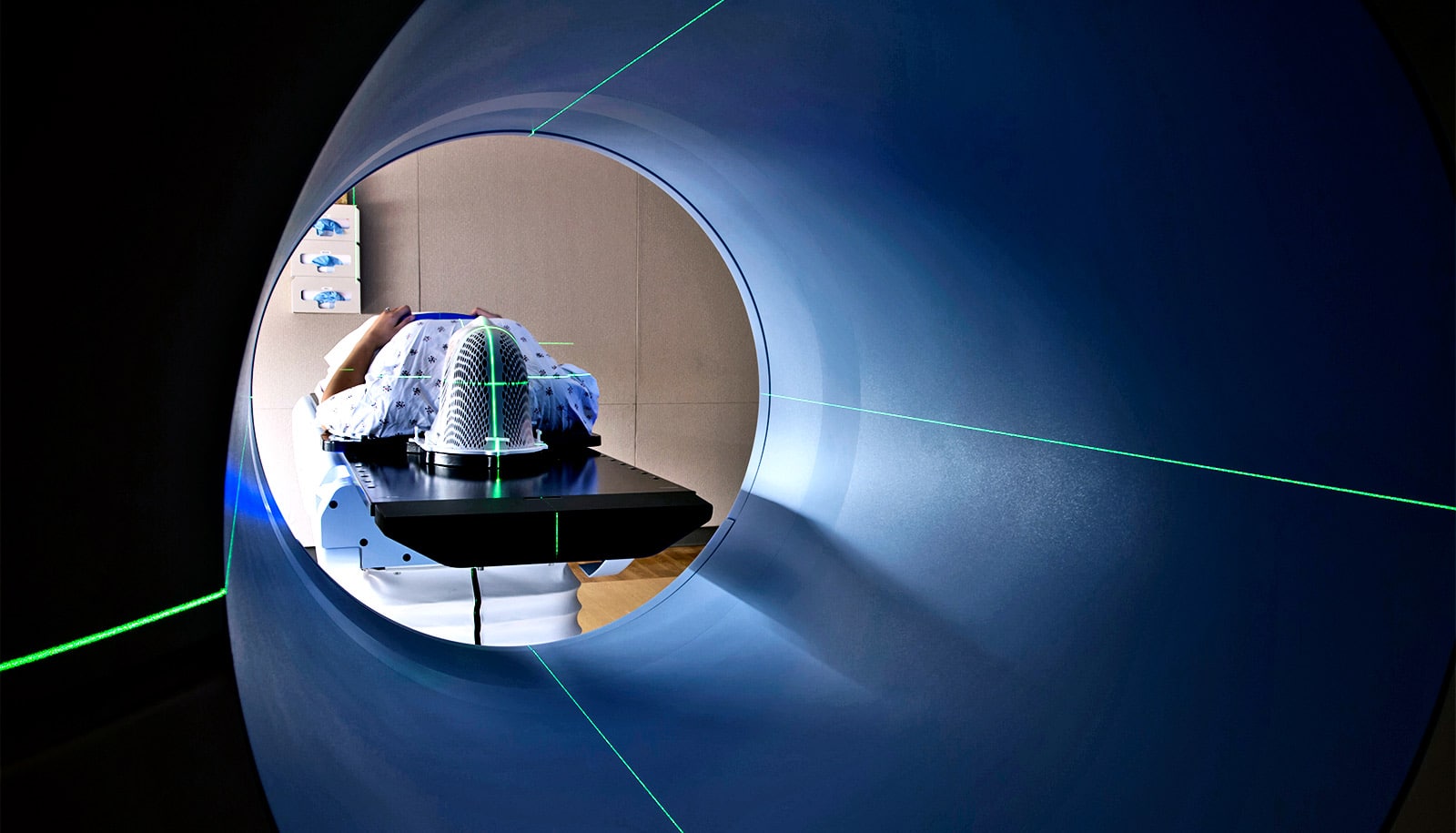

The volunteers underwent a battery of tests that measured cognitive performance, functional performance, and behavior, and brain imaging and monitoring of biomarkers of the disease. The drug was associated with extremely robust amyloid plaque clearance; most of the participants at 18 months had no detectable plaques in their brain.

Other downstream effects associated with Alzheimer’s, like tau and neuronal inflammation biomarkers, also looked like they moved more towards normal.

There was a statistically significant separation between participants who received the drug compared to those who received a placebo on global measures of cognitive and functional impairment, keeping in mind that participants in the study had a confirmed diagnosis of Alzheimer’s but their cognitive symptoms were still very mild at the time of their enrollment.

This provides the first definitive evidence that clearing amyloid beta improves cognitive performance. It is important to note that both groups experienced cognitive decline over the 18 months of the study, but the placebo group declined at a faster rate.

About 12.5% of participants showed evidence of mild to moderate localized brain swelling, but this was not life threatening, rarely clinically evident, and resolved over several weeks when the medication was temporarily halted.

We also saw a higher rate of micro hemorrhages, or pinhead bleeds, that we often see in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, so the treatment requires careful clinical and MRI monitoring, particularly in the first 6-12 months.

Why has it been so difficult to develop new treatments for AD?

Alzheimer’s is a very complex, multi-modal disease that varies from person to person. This is also a disease where the changes in the brain start maybe 20 to 25 years before you have any clinical symptoms. By the time someone presents with symptoms they are actually very late in the overall disease course.

Amyloid beta is probably one of the driving forces of Alzheimer’s disease, but definitely not the only one. Tau, neuro-inflammation, and oxidative stress all play a role. This is a disease that will ultimately require combination treatments like some of the resistant cancers, or resistant high blood pressure, or diabetes.

Those of us who have been studying Alzheimer’s for a long time have become humble and we recognize that lecanemab is a start and not a cure. It is a modest start, but represents an approach to treatment that we can build upon.

Given there are challenges in diagnosing AD, how do you identify patients in early stages of the disease who may benefit from this treatment?

We have the ability through complex amyloid PET scans and cerebral spinal fluid analysis to confirm that someone has amyloid plaque burden and therefore Alzheimer’s disease, but in the last few years there has really been a revolution in blood biomarkers and they are now becoming commercially available.

This is really going to transform the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. If someone is experiencing memory problems, their physicians will be able to order a blood test that will tell us if this is the result of changes in your brain due to Alzheimer’s disease. This will ultimately make it much easier to identify people at a very early stage of the disease, where they are most likely to benefit from treatment.

What are the next steps and when do we anticipate it will be available for patients?

Given the benefits seen with lecanemab, I expect the Food and Drug Administration to grant “accelerated approval” in early 2023. This will allow the drug to be administered to a limited number of patients participating in a registry study and the agency will most likely give full approval based on clinical benefit in about 9 months.

While this medication is not for everyone with Alzheimer’s disease it represents a significant first—a disease modifying treatment with [indisputable] evidence of clinical efficacy.

Biogen and Eisai funded the clinical trials and company scientists cowrote the study.

Source: University of Rochester