Researchers have identified a unique process within the environment of deadly brain tumors that drives resistance to immune-boosting therapies.

The process could potentially be a target to promote the effects of those drugs.

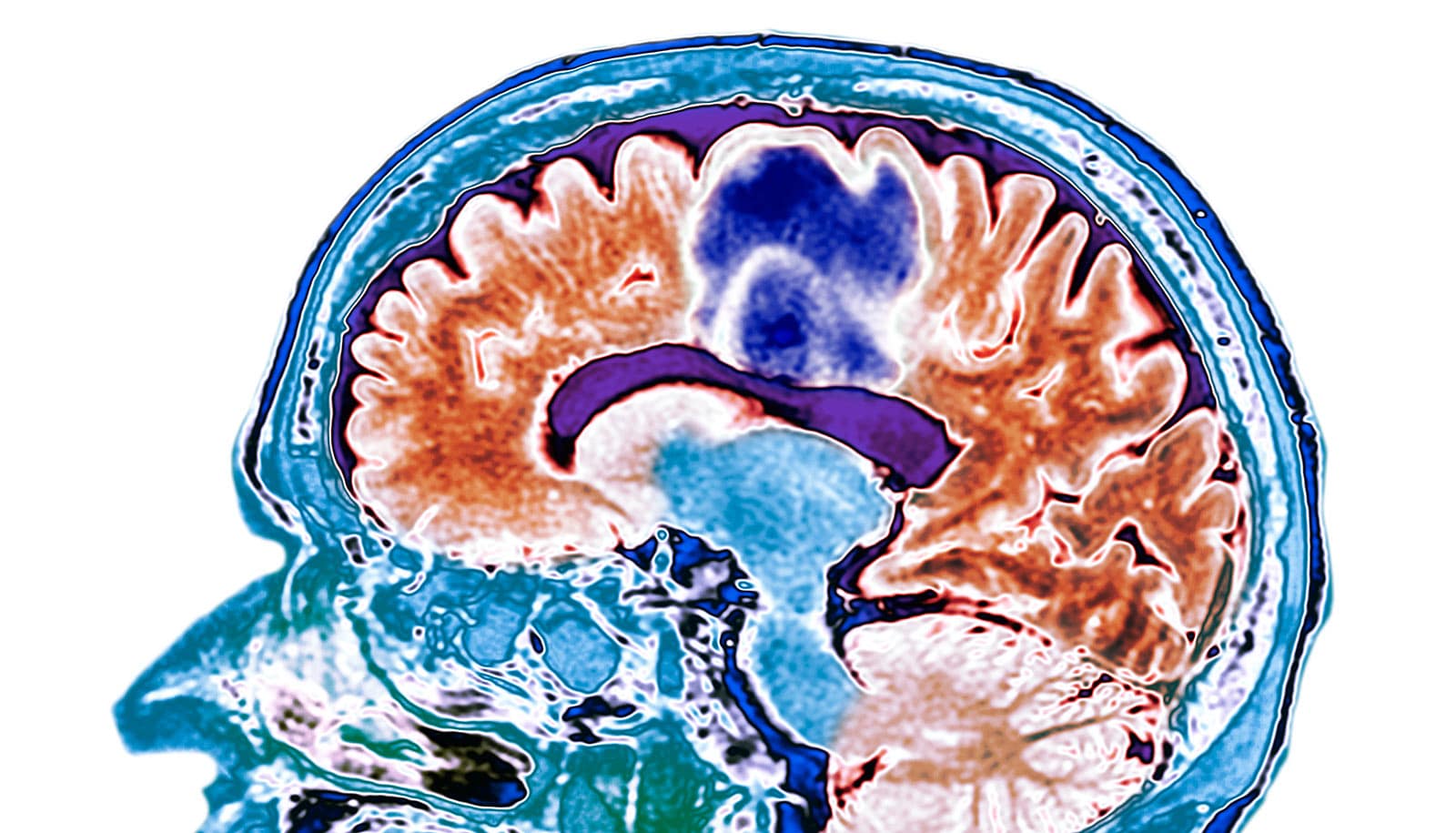

The finding, published in Nature Communications, explains a vexing problem in glioblastoma, a deadly form of brain tumor that has proven notoriously impervious to immune checkpoint inhibitors, a type of immunotherapy which has been highly effective in other cancers.

“Researchers have traditionally approached immunotherapy and resistance either by looking at cancer cells to find targets to attack, or by exploring the tumor environment for potential ways to improve the immune response,” says lead author William H. Tomaszewski, who conducted the studies as a doctoral candidate in Duke University’s neurosurgery department. “Our approach in this work was to find environmental factors that could make glioblastoma more vulnerable to immunotherapies.”

Tomaszewski and colleagues—including senior author John Sampson, professor of neurosurgery—focused on a molecule known as calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase 2, or CaMKK2, which is present in neurons and immune cells. This molecule is highly active in cancer supporting cells in the glioblastoma environment and is associated with worse survival in humans.

In mouse studies, the cancer-killing T-cells were inhibited from attacking brain tumor cells in animals with high levels of CaMKK2. Among mice bred without CaMKK2, T-cells remained aggressive cancer killers.

Not only did CaMMK2 affect T-cell function, but the protein also changed the behavior of macrophages, making these immune cells less helpful to T-cells. Here again, when CaMMK2 was eliminated, the macrophages aided in tumor killing.

One surprising finding was that CaMKK2, specifically in neurons, was supporting brain tumor growth and suppressing the function of the immune system. Understanding how neurons do this may identify additional therapeutic targets in the future.

Because CaMKK2 is highly expressed in tumor-supporting neurons and macrophages, the researchers say it promotes resistance to immune-checkpoint inhibitor drugs, which turn off a cellular brake to accelerate the cancer-killing ability of T-cells.

“When mice without CaMMK2 were treated with checkpoint inhibitors, they responded and survived even longer, but mice with CaMKK2 did not,” Tomaszewski says.

“This suggests that CaMKK2 represents a potential therapeutic target. If we could inhibit CaMMK2, we might be able to unleash the power of the whole class of immunotherapy drugs that have been beneficial in other cancers, but not glioblastoma.”

The National Institutes of Health supported the work.

Source: Duke University