Findings from a new disease model may help public health officials evaluate and improve strategies for the next pandemic, researchers say.

Nearly two years ago, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released its recommendations for a phased COVID-19 vaccine rollout. The agency prioritized groups based on occupation, age, living condition, and high-risk medical conditions in an effort to protect the vulnerable and reduce deaths.

But future pandemic responses should also consider ethnicity and social contact patterns that affect disease dynamics, says Claus Kadelka, assistant professor of mathematics at Iowa State University and lead author of a new paper in the Journal of Theoretical Biology.

“Many researchers in this field focus primarily on age. Who should get the vaccine first: older people who are the most vulnerable or younger people who have more contacts and can more easily spread the disease? Not considering other social dimensions when developing a vaccination strategy can lead to different or wrong predictions about the best way to prevent deaths,” says Kadelka.

The researchers point to multiple studies showing that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected people of color. The infection rate in predominantly Black counties in the US was three times higher than predominantly white counties in 2020, and the Navajo Nation had more cases per capita than any state in the country.

One reason for the disparity, the researchers say, is that people of color are more likely to work in public-facing and high-contact jobs (e.g., transportation services, grocery stores, meat packing facilities), which do not easily allow for physical distancing and remote work.

People of color are also more likely to live in higher-density or multi-generational housing where it’s harder to quarantine and prevent the spread of the virus.

Using data from the CDC, the US Census Bureau, and the US Bureau of Labor, the researchers applied a model they developed last year and incorporated different contact rates and occupational hazards by age and ethnicity. They then used the Iowa State supercomputer to analyze 2.9 million different vaccination strategies to identify those that achieved specific goals, such as minimizing infections or deaths from COVID-19.

“Our first big take-away from the study is that ‘ethnic homophily,’ the concept that people tend to interact more frequently with people from the same demographic group, matters,” says Kadelka. “The best strategy that included ethnicity prevented more deaths than the best strategy without ethnicity.”

The second big finding, Kadelka says, is less intuitive.

“When trying to minimize the number of deaths, it is best to get the vaccine to the oldest people of color first, because they are at immediate risk, followed by working-age non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Asians with high-contact jobs, so they stop spreading the virus through the community.”

As to whether the optimal pandemic vaccine strategy in the model would have had the same effect in the real world, Kadelka says it’s hard to know because many social and disease characteristics, like detailed contact patterns and factors affecting susceptibility to infection, are still poorly understood. But he hopes the study will spur more research in the intersection of epidemiology and sociology.

The researchers emphasize that prioritizing COVID-19 vaccine access based on ethnicity is not a theoretical concept. Two states, Montana and Vermont, opened vaccine eligibility to people of color before the general public in the spring of 2021. They also cite a study that found three dozen states set aside some of their allotted vaccines for certain residents and communities based on disadvantages in income, education, and housing.

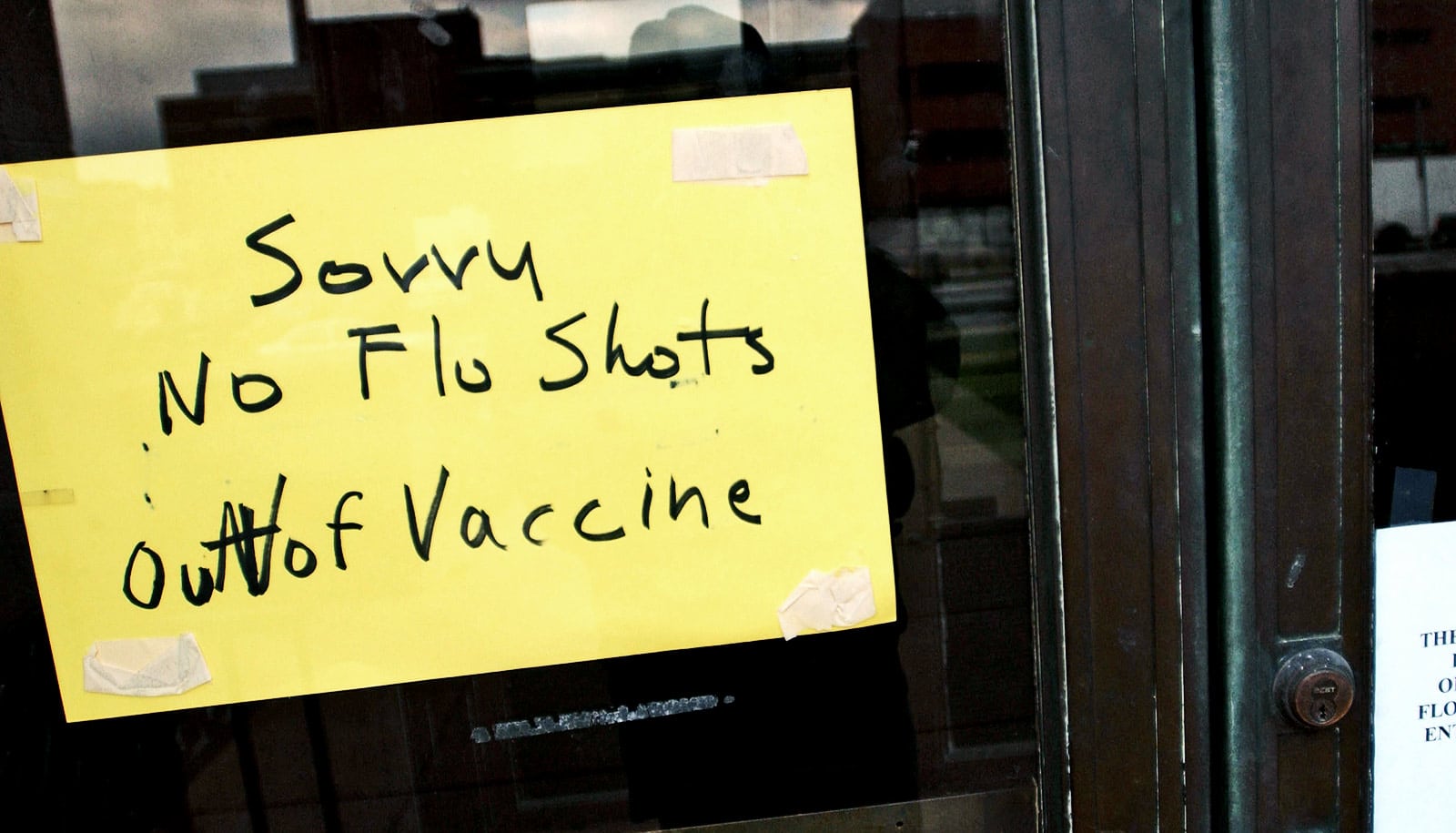

Disease models, like the one Kadelka’s team developed and are continuing to work on, may help public health officials improve strategies when vaccines are in limited supply.

Source: Iowa State University