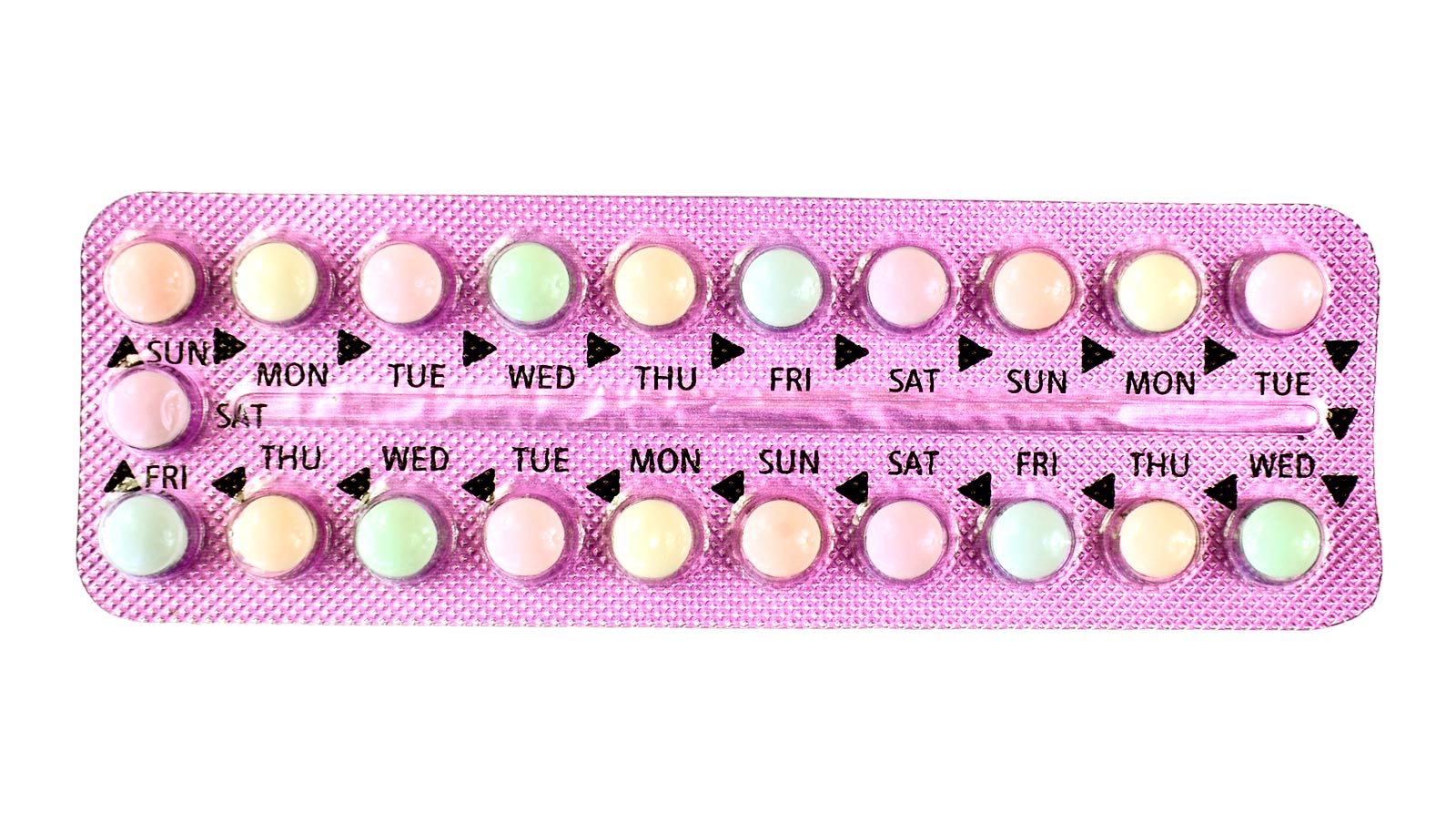

Researchers have developed a computer model that flags drug combinations that could reduce the effectiveness of contraception.

Many contraceptive users may not realize taking additional medications can reduce the effectiveness of birth control, leading to unintended pregnancies.

In the journal Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, researchers describe how they developed a computer model and validated the findings in real-world data to compare hormonal contraceptive drug products when taken alone or in combination with other medications.

The model will help regulators, as well as the pharmaceutical industry, evaluate the best- and worst-case scenarios when hormonal contraceptives are prescribed with new drug candidates.

“There is an urgent public health need to understand how drug interactions are leading to unplanned pregnancies,” says Stephan Schmidt, professor in the University of Florida College of Pharmacy and director of the Center for Pharmacometrics and Systems Pharmacology. “We have more than 300 million women worldwide who are susceptible to these drug interactions, and the evidence suggests up to a 50% failure rate in low- and middle-income countries.”

Contraceptive failure rates are lower in the United States than in Sub-Saharan Africa and countries where widespread diseases, such as HIV and tuberculosis, require multiple medications. Women taking these drugs are susceptible to unintended pregnancies because HIV and tuberculosis medications induce CYP3A4, an enzyme that helps release the progestins found in hormonal contraceptives into the bloodstream.

“It’s the scenario where one drug has the potential to change the speed at which the body gets rid of the other drug,” Schmidt says. “If drug concentration levels drop faster than intended, then birth control medications are at an increased risk of being ineffective at preventing pregnancy.”

The researchers examined multiple hormonal contraceptives—formulated with different ingredients—to identify the risk of drug interactions causing unplanned pregnancies. In the best-case scenario, they found oral hormonal contraceptives to be 100% effective, however, this efficacy rate can diminish due to various factors without the use of secondary protection.

The upper and lower boundaries were established using a computer-aided modeling approach called pharmacokinetic bracketing. The researchers developed the model to simulate and evaluate drug interactions that may not be frequently studied in the real world. Using real-world data, the researchers compared the rate of unintended pregnancy among women using different hormonal contraceptives who were exposed to drug interactions.

“Our main goal was to provide a developmental framework for drug regulators and the pharmaceutical industry to use when they evaluate and develop new drug products,” says Brian Cicali, a research assistant professor of pharmaceutics in the University of Florida College of Pharmacy and a co-lead author of the study with Amir Sarayani and Lais Da Silva.

“The thresholds defined for these hormonal contraceptives will help develop novel formulations to improve medication access and use in low- and middle-income countries.”

This research supports ongoing global drug development and regulatory evaluation efforts led by the departments of pharmaceutics and pharmaceutical outcomes and policy in the university’s College of Pharmacy and supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In addition, Bayer has served as an industry collaborator on the research and guided modeling efforts and clinical pharmacology of their compounds.

Source: University of Florida