The extinct megalodon, Otodus megalodon, could take down prey as large as a modern orca, research finds.

This places megalodon at a higher trophic level than modern top predators.

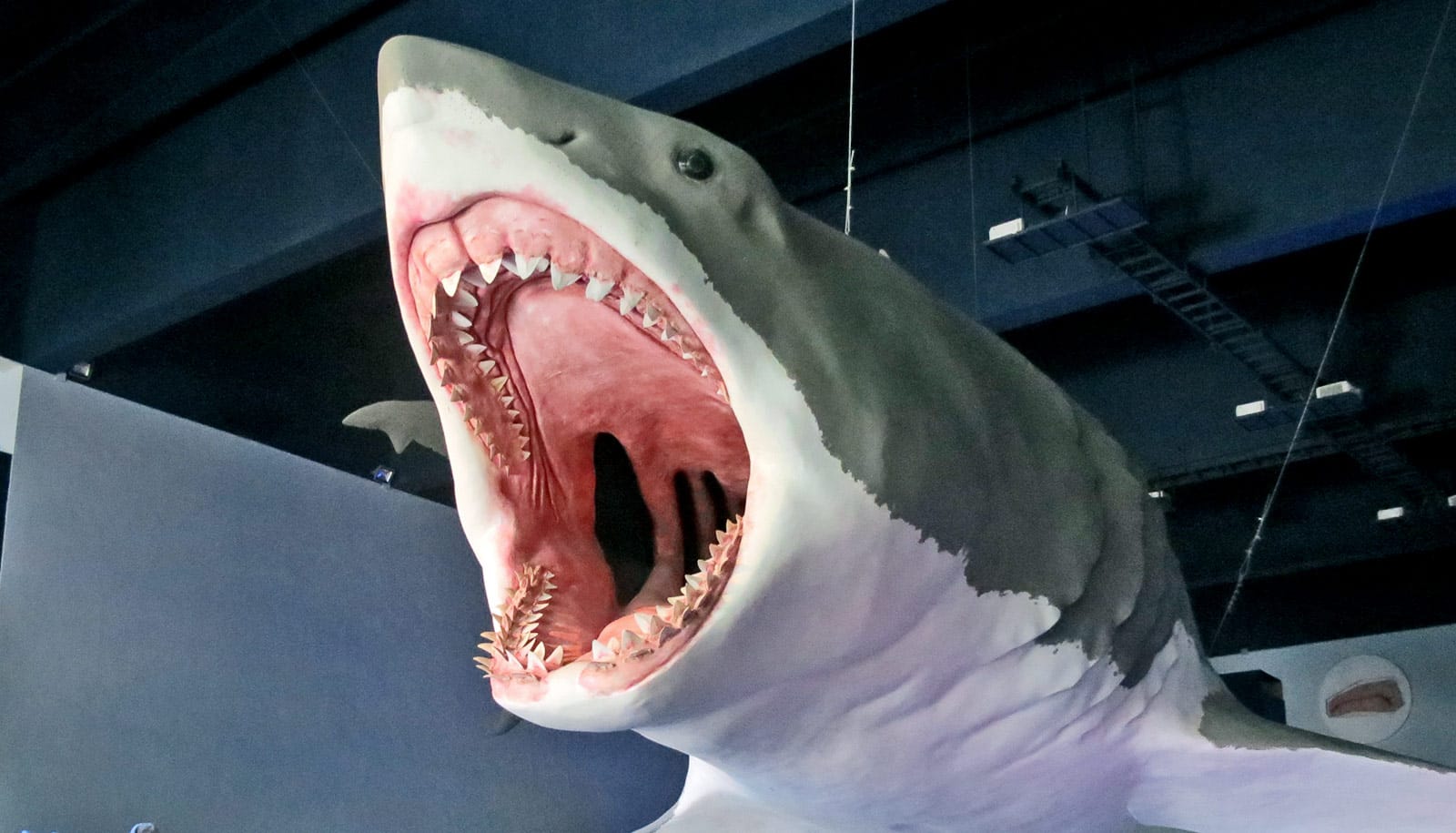

Researchers find that the reconstructed megadolon was 52 feet (16 meters) long and weighed over 61 tons. They estimate that it could swim at around 3 miles per hour (1.4 meters per second), require over 98,000 calories every day, and have stomach volume of almost 2,642 gallons (10,000 liters).

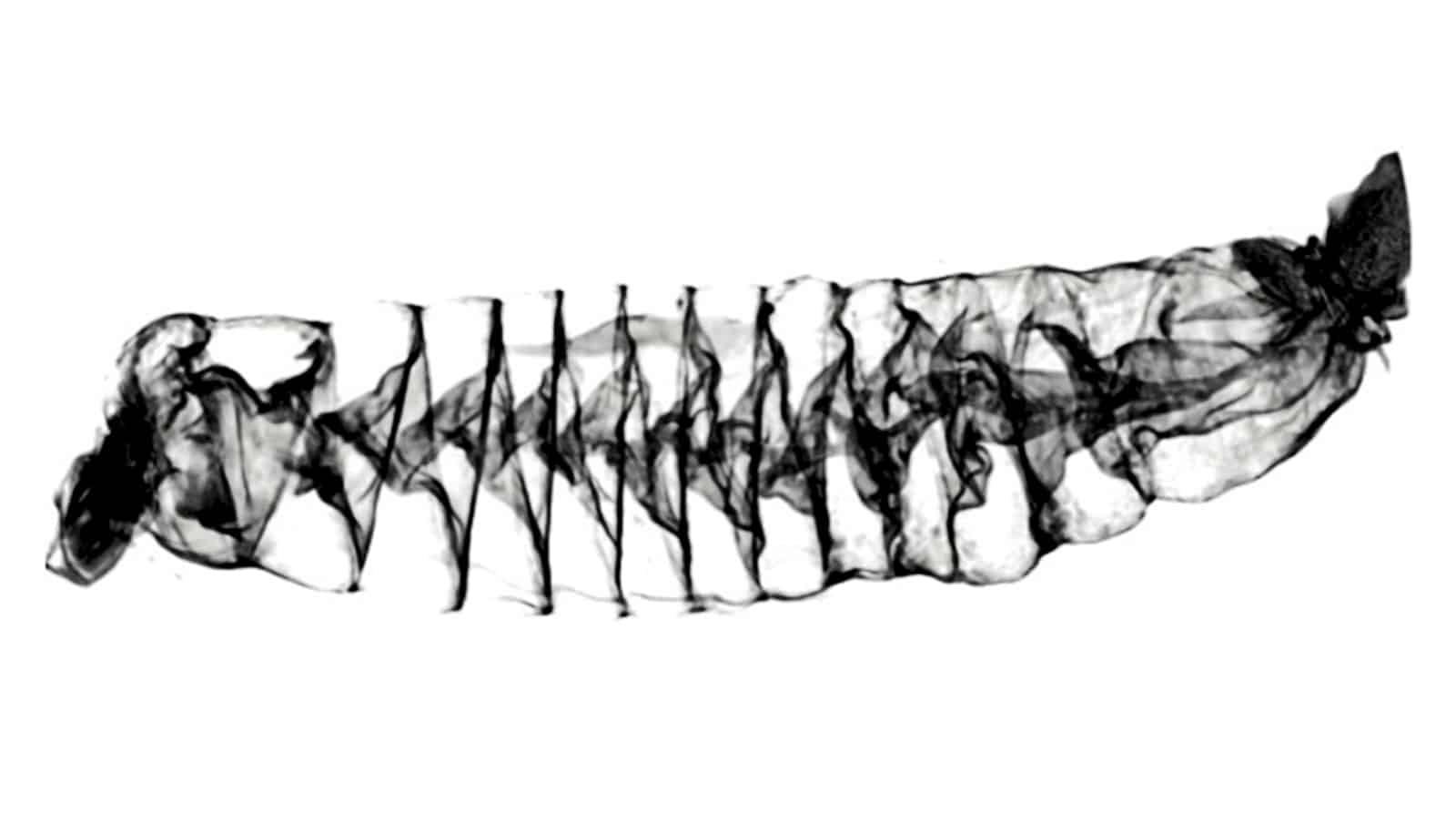

The research was possible due to the 3D modeling of one individual megalodon which was discovered in the 1860s. Against all odds, a sizable portion of its vertebral column was left behind in the fossil record after the creature died in the Miocene oceans of Belgium at the age of 46 about 18 million years ago.

“Shark teeth are common fossils because of their hard composition which allows them to remain well preserved,” says first author Jack Cooper, PhD student at Swansea University. “However, their skeletons are made of cartilage, so they rarely fossilize. The megalodon vertebral column from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences is therefore a one-of-a-kind fossil.”

The research team first measured and scanned every single vertebra before reconstructing the entire column. They then attached the column to a 3D scan of a megalodon’s teeth from the United States. They completed the model by adding “flesh” around the skeleton using a 3D-scan of the body of a great white shark from South Africa.

“Weight is one of the most important traits of any animal. For extinct animals we can estimate the body mass with modern 3D digital modelling methods and then establish the relationship between mass and other biological properties such as speed and energy usage,” says coauthor John Hutchinson, professor at the Royal Veterinary College in the UK.

The high energetic demand would have been met by feeding on calorie-rich blubber of whales, in which megalodon bite marks have previously been found in the fossil record. An optimal foraging model of potential megalodon prey encounters found that eating a single 26-foot-long (8-meter-long) whale may have allowed the shark to swim thousands of miles across oceans without eating again for two months.

“These results suggest that this giant shark was a trans-oceanic super-apex predator,” says Catalina Pimiento, professor at the University of Zurich and senior author of the study. “The extinction of this iconic giant shark likely impacted global nutrient transport and released large cetaceans from a strong predatory pressure.”

The complete model can now be used as a basis for future reconstructions and further research. The novel biological inferences drawn from this study represent a leap in our knowledge of this singular super predator and helps to better understand the ecological function that megafaunal species play in marine ecosystems, and the large-scale consequences of their extinction.

The research appears in Science Advances.

Source: University of Zurich