Researchers report a new way to monitor the placenta in pregnant patients.

By combining optical measurements with ultrasound, the findings show how oxygen levels can be monitored non-invasively and provides a new way to generate a better understanding of this complex, crucial organ.

Findings from the pilot clinical study appear in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

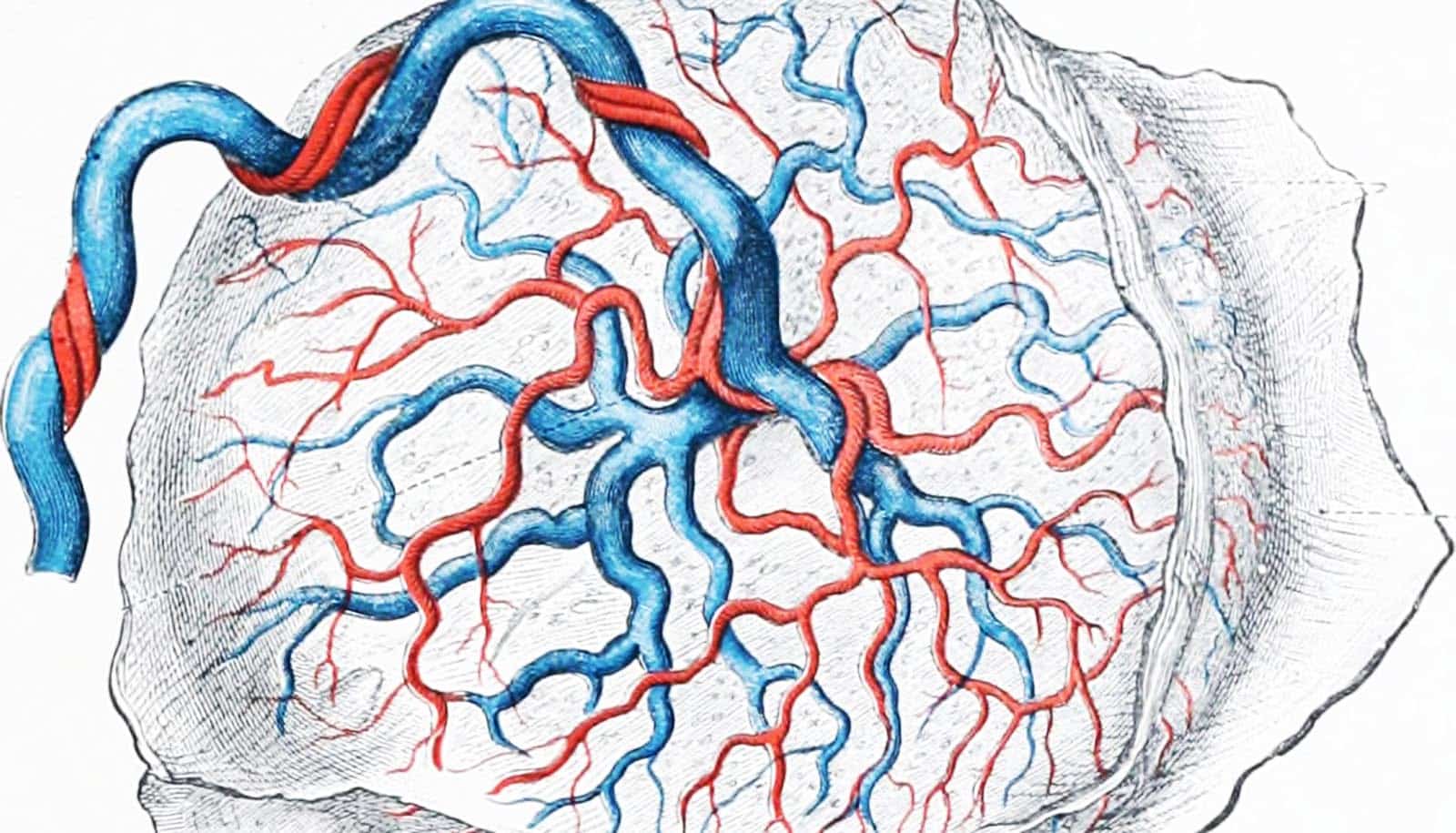

Nadav Schwartz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Pennsylvania, describes the placenta as the “engine” of pregnancy, an organ that plays a crucial role in delivering nutrients and oxygen to the fetus.

Placental dysfunction can lead to complications such as fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, and stillbirth. To increase knowledge about this crucial organ, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development launched the Human Placenta Project in 2014. One focus of the program is to develop tools to assess human placental structure and function in real time, including optical devices.

How to monitor the placenta

For three years, the researchers optimized the design of their instrument and tested it in preclinical settings. The process involved integrating optical fibers with ultrasound probes, exploring various ultrasound transducers, and improving the multi-modal technology so that measurements were stable, accurate, and reproducible while collecting data at the bedside.

The resulting instrumentation now enables researchers to study the anatomy of the placenta while also collecting detailed functional information about placenta blood flow and oxygenation, capabilities that existing commercially devices do not have, the researchers say.

Because the placenta is located far below the body’s surface, one of the key technical challenges addressed by study leader Lin Wang, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Arjun Yodh, was reducing background noise in the opto-electronic system. Light is scattered and absorbed when it travels through thick tissues, Yodh says, and the key for success was to reduce background interference so that the small amount of light that penetrates deep into the placenta and then returns is still large enough for a high-quality measurement.

“We’re sending a light signal that goes through the same deep tissues as the ultrasound. The extremely small amount of light that returns to the surface probe is then used to accurately assess tissue properties, which is only possible with very stable lasers, optics, and detectors,” says Yodh, professor and chair in the department of physics and astronomy. “Lin had to overcome many barriers to improve the signal-to-noise ratio to the point where we trusted our data.”

Notably, the paper also describes the results of a pilot study where 24 pregnant patients in their third trimester received supplemental oxygen for a short time period, creating placental hyperoxia. Using the device, the team collected measurements of the placenta’s oxygenated and deoxygenated blood concentrations before and during hyperoxia; the results demonstrated that the device could be used to study placental function in real time. The research also provided new insights into the relationship between blood flow and maternal vascular malperfusion, which occurs when blood flow into the placenta is impeded.

“Not only do we show that oxygen levels go up when you give the mom oxygen, but when we analyze the data, both for clinical outcomes and pathology, patients with maternal vascular malperfusion did not have as much of an increase in oxygen compared to patients with normal placentas,” says Schwartz. “What was exciting is that, not only did we get an instrument to probe deeper than commercial devices, but we also obtained an early signal that hyperoxygenation experiments can differentiate a healthy placenta from a diseased placenta.”

Improving the instrument

While the device is still in development, the researchers are currently refining their instrument to make it more user-friendly and to allow it to collect data faster. The team is also currently working on larger studies, including recently data from patients during their second trimester, and they are also interested in studying different regions of the placenta. “From an instrumentation perspective, we want to make the operation more user-friendly, and then we want to carry out more clinical studies,” Wang says about the future of this work.

And because there are many unanswered clinical questions about the placenta, for Schwartz the biggest potential of this work is in providing a way to start answering those questions. “Without being able to study the placenta directly, we are relying on very indirect science,” he says. “This is a tool that helps us study the underlying physiology of pregnancy so we can more strategically study interventions that can help support good pregnancy outcomes.”

Coauthors of the paper are from Penn, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School. Funding came from the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Penn