Educator Jennifer Wolf puts book banning in context, from Nazi book burnings to school board races.

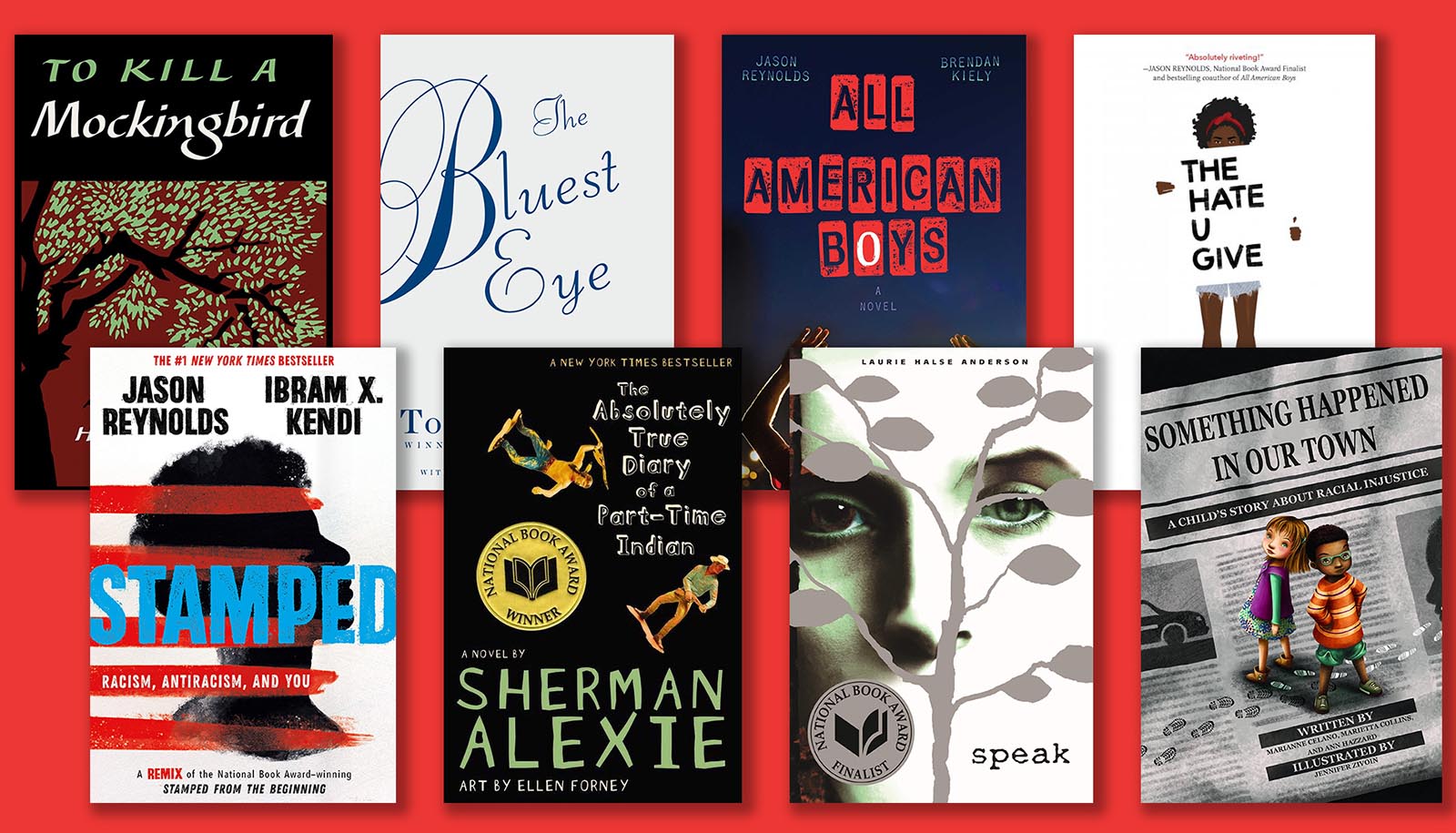

Efforts to ban books in the United States have surged at a rate the American Library Association calls “unprecedented,” with attempts currently at their highest level since the organization began tracking them 20 years ago.

“One of the first Nazi book burnings took place at a clinic that researched and performed gender confirmation surgery and housed a library of books on the subject.”

A few high-profile examples: In January, a Tennessee county school board voted unanimously to remove the Pulitzer Prize-winning book Maus from eighth grade lessons on the Holocaust. Last fall, Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin made book banning a focal point of his successful 2021 campaign, targeting Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved. And Texas legislators recently passed HB 3979, which bans the teaching of any materials that could result in “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of the individual’s race or sex.”

Jennifer Wolf, a senior lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), teaches courses in young adult literature, including a class on the genre for undergraduates interested in teaching or working with adolescents. She is also the director of undergraduate programs at the GSE (UP@GSE), which hosted a teach-in on book banning this spring.

Here, Wolf discusses how approaches to book banning have changed over the years, teachers’ responsibility to students when challenges arise, and the now-prominent role parents play in pushing for books to be removed from schools:

How do the current book challenges compare with efforts from the past?

I think for many of us, the history of book banning brings to mind some of the images of Nazi book burnings of the 1930s, which was fictionalized a couple of decades later in Fahrenheit 451. In fictionalizing the practice, I think we’ve allowed ourselves to think it’s something that couldn’t happen again, and yet folks who are really committed to book banning right now are using a lot of the same strategies that we saw in the past.

One thing that’s interesting and different is that, when the Nazis instigated book banning as part of their political agenda, they included young people in the role of finding and burning books. Students were given the job of finding books that fit the criteria set by the Nazis—there weren’t lists of titles like there are now, there were qualities or types of books. And students were in charge of finding those books and leading the whole ritual of burning the books in public. I’m sure it was a pretty enticing handover, to invite young people to lead this very dramatic ritual.

What about the nature of the books being targeted?

The types of books that the Nazis wanted removed and burned were largely political, with ideologies opposed to Nazism, including books on race and sexuality. One of the first Nazi book burnings took place at a clinic that researched and performed gender confirmation surgery and housed a library of books on the subject.

“Learning involves growth, and growth involves stretching and changing. That’s not always comfortable…”

Today we find that book bans supposedly targeting a particular issue often go well beyond it. After the Texas House passed HB 3979, the so-called “critical race theory” law, a state legislator sent a 16-page spreadsheet of 850 titles to the Texas Education Agency, asking if any of the schools had the books listed in order to verify compliance with the bill. But when we look closely at the titles on that list, the majority of the books on the list are about LGBTQ+ identity and sex education. That’s why it’s important to pay attention to the actual titles that are singled out, to see what the bans are really about.

This contemporary push seems to be a response to people coming forward and asking for more diverse representation in the books that are available in schools, either in the curriculum or in school libraries. I think it’s a reaction to more people asking for their voice to be heard in the discussion about how we represent identity and teach it to our kids.

It seems like there’s also a new dimension in the way teachers and librarians are being aggressively targeted, treated as criminals for including or allowing these books.

My understanding is that the legal avenues that legislators and school boards have tried to put in place have no teeth. But they have a great deal of power in diminishing morale and increasing fear. At a time when we’re facing an acute teacher shortage, why in the world would we want to threaten and frighten teachers and librarians out of their profession?

School librarians are an interesting player in all this. There are books that are part of the curriculum, and then there are books that are in school libraries. It’s one thing to say, “I don’t want this book taught in the classroom.” It’s another to say, “I don’t want any student to be able to have access to this book”—a book that could answer their questions, affirm their identity, save them.

Parents also seem much more engaged in these efforts.

Absolutely. For years in my teaching, my message has been: Get involved in the education democracy. Do you know who’s on your local school board? Do you know who’s running? Do you understand your responsibility to participate? And now we have whole swaths of people showing up to school board meetings, running for the school board, saying, “I don’t want my child reading this book. It’s not the way I want to raise my child. I don’t want my child to feel uncomfortable.” This puts parents at odds with the teaching profession, after we’ve prepared and credentialed and put our trust in teachers to do what’s best for kids to learn.

Do teachers have a responsibility to act on parents’ concerns?

We talk a lot in teacher preparation studies about teachers’ responsibility to create a safe space in the classroom. That’s different from a comfortable space. Learning involves growth, and growth involves stretching and changing. That’s not always comfortable, but it’s productive and necessary. I’ve read many of these books that are being challenged, and I can attest—they do push us outside of our comfort area.

Part of the way we use literature in our lives is to grow and stretch us—to teach us how to read life, how to understand character, how to decide who’s trustworthy, how to anticipate what will happen next, and learn from what’s already happened. The things we do inside the plot of strong literature are things we want our young people to do outside the pages of the book. And there’s going to be some discomfort.

Source: Stanford University