Counties in Washington state that started supplementing revenue with court-imposed fines also increased the rate at which they sentence women to jail, research finds.

According to new research, this association indicates that monetary sanctions, also known as legal financial obligations or LFOs, have far-reaching social, economic, and punitive effects. In other words, what may seem like a system of low-level penalties (like traffic citations and court processing fees) aimed at individuals actually affects whole communities.

“Here in Washington state, men’s incarceration rates have been trending downward for over a decade whereas women’s incarceration rates have continued to increase,” says lead author Kate O’Neill, a postdoctoral researcher in sociology at the University of Washington.

“This paper suggests this is because women have not benefitted from the legal system’s shift away from carceral sentencing toward monetary sanction sentencing in the same ways men have benefitted.”

The study is part of a volume of research on legal financial obligations, published online in January in The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. Alexes Harris, professor of sociology, spearheaded the study of trends and practices in eight states over five years relating to legal fines and fees.

The study focuses on Washington state, and looked at the connection between a defendant’s gender and fines and fees.

Over the past two decades, women’s incarceration rates have remained steady or increased nationwide. The researchers wanted to use Washington state data to explore what factors may contribute to this trend, and specifically, whether the expanding system of monetary sanctions could be to blame.

The authors, including sociology graduate students Tyler Smith and Ian Kennedy, used county-level statistics from the Washington Administrative Office of the Courts from 2007-2012, as well as county budget information from the Washington State Auditor and demographic data from the US Census Bureau.

In the United States, more women live in poverty than men, and people who are poor are disproportionately affected not only by the legal system generally, but also by monetary sanctions in particular.

“Among people who commit crime, women are disproportionately represented among misdemeanor offenders…”

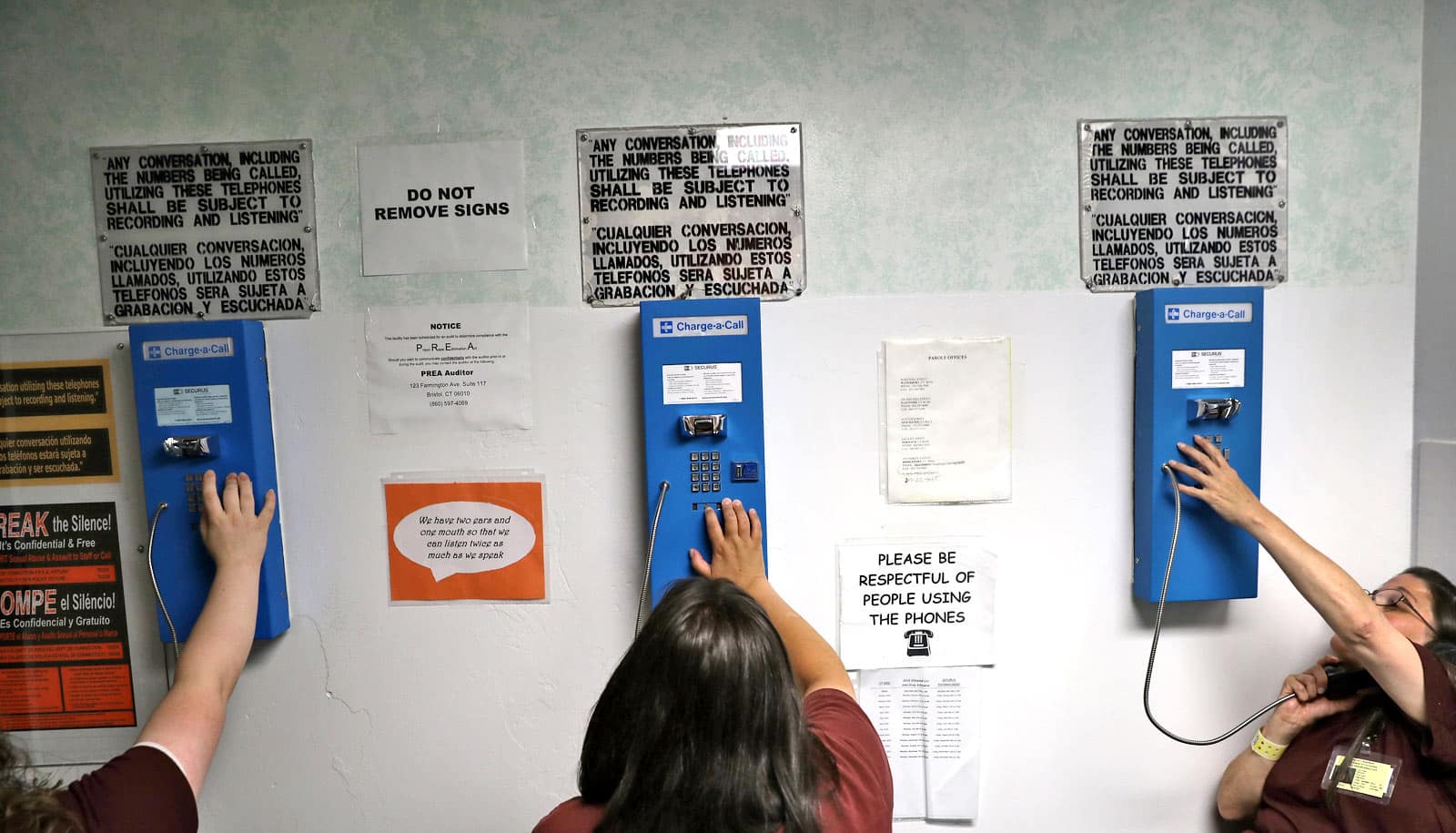

Monetary sanctions, meanwhile, have contributed a growing share of local government revenues in communities around the country. The study finds that, among Washington’s 39 counties, a 1% increase in county revenue from monetary sanctions was, on average, associated with a 23% increase in the incarceration rate of women. That may be due, researchers say, to increased law enforcement around the types of lower-level offenses women are more likely to engage in than men, and to the possibility that women, due to financial precarity, are forced to opt for incarceration because of their inability to pay fines and fees.

“Not only are women going to find financial sentences more burdensome than men, they are also more likely to commit the types of crime that make them eligible for monetary sanctions instead of incarceration,” O’Neill says.

“Among people who commit crime, women are disproportionately represented among misdemeanor offenders, whereas men commit more felonies. So, women who offend may be more likely to be sentenced to monetary sanctions and less likely to be able to pay than men who offend.”

Given the association the study shows between revenues from monetary sanctions and the sentencing of women to incarceration in Washington counties, the researchers suggest that governments look for other revenue sources, and for ways to reduce the costs of their justice systems. The authors point to a 2019 article in Governing on the spatial distribution of monetary sanction debt and revenue that suggests these findings could apply outside of Washington state as well.

“Heavy reliance on monetary sanctions as a source of revenue creates an obvious conflict of interest for local governments: They need people to violate the law in order to keep themselves out of the red,” O’Neill says.

“Capping the annual proportion of local expenditures derived from monetary sanctions, or earmarking the monetary sanction revenue for community programs that address the root causes of crime, would go a long way in alleviating the social problems associated with the system. Or—even better—get rid of the system of monetary sanctions altogether.”

This study had funding from a grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development to the UW Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology, and as part of the eight-state study by Arnold Ventures.

Source: University of Washington