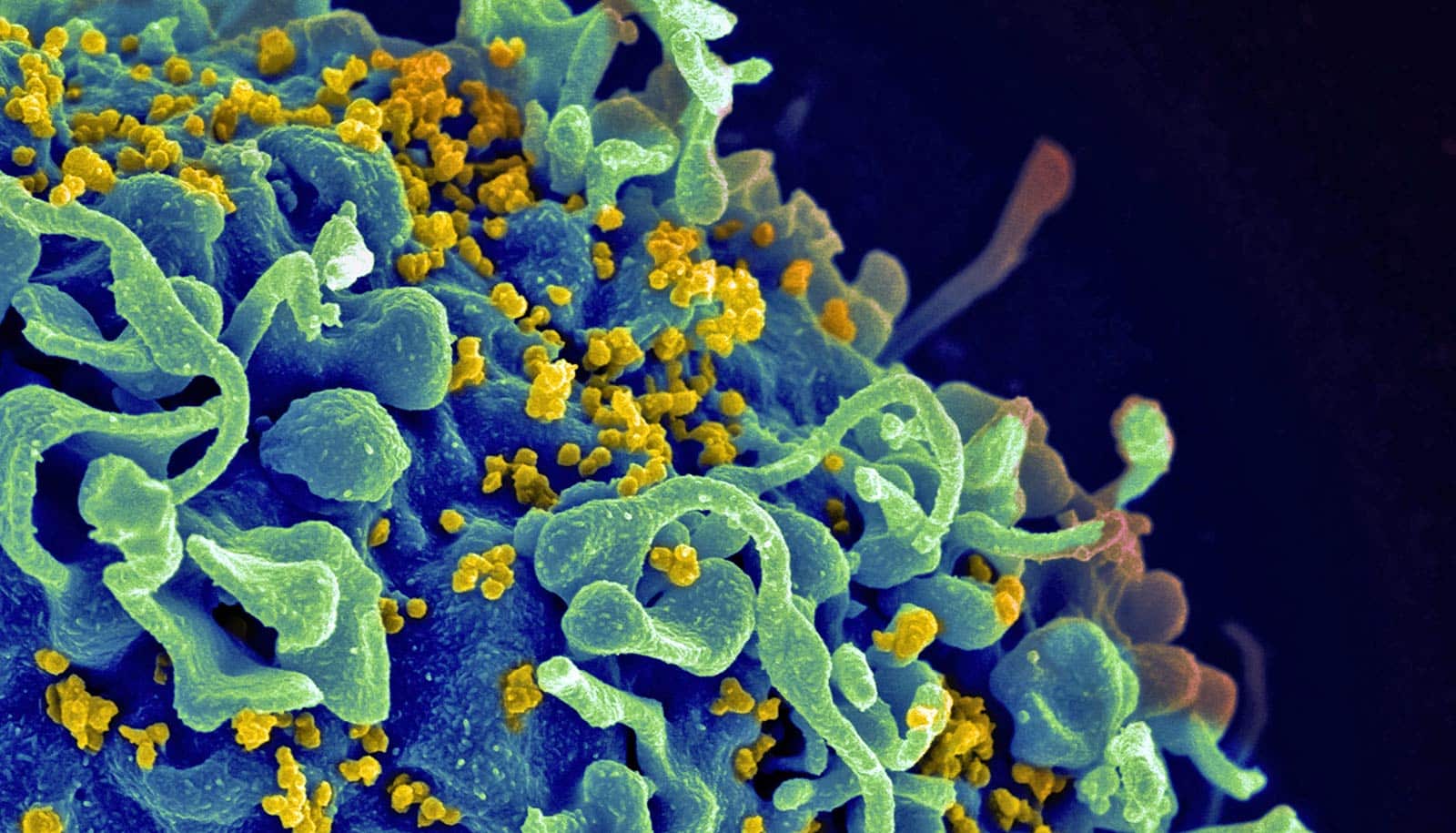

Using powerful tools and techniques developed in the field of structural biology, researchers have discovered new details about the human immunodeficiency virus, HIV.

The findings bring into focus the basic architecture of HIV just above and below its surface and may help in the design and development of a vaccine that can protect against AIDS.

These detailed findings include 3D views of the structure and position of the virus’ envelope “spike” proteins (the Env protein, used when the virus binds with cells) in the context of the full virus. Normally, researchers view the protein particles separated from the virus or expressed as engineered or purified proteins.

In another key development, the study sheds new light on the glycan shields—the sugars on the proteins that can hide it from the body’s immune system.

“We’re looking at the whole virus particle and how this protein on the surface relates to the rest of the virus,” says lead author Kelly Lee, associate professor of medicinal chemistry in the University of Washington School of Pharmacy. “And by looking at the intact virus structure, we can see how the different facets of this ‘face of the virus’ are being displayed and how they would be recognized by or hidden from the immune system.”

This intact view of the virus also allowed the scientists to gain new insights into positioning of the envelope spike protein on the surface relative to the internal protein structure, called the Gag lattice.

“This finding overturns previous models of how the parts of the viruses are assembled and helps to focus our attention on where the docking interaction of these two proteins is likely to be,” Lee says. “This interaction needs to be resolved in more detail, but at least the current work gives us the correct architectural model for the virus assembly.”

As reported in Cell, another of the paper’s findings, not previously observed, is that the “stalk” supporting the envelope proteins is flexible and can tilt, presenting both opportunity and challenges to the immune system’s neutralizing antibodies that protect cells from infection.

“Structural biology has driven HIV vaccine design, so as we get a better and better picture of what it is we’re targeting, that inspires innovation and may lead to improved vaccines,” says co-corresponding author Michael Zwick, associate professor of immunology and microbiology at Scripps Research.

HIV’s envelope presents a particularly difficult target for vaccine development, Zwick adds, because the virus displays so few spikes and camouflages them with sugar molecules so as to evade our immune system.

“All these features increase the dynamic variability that the HIV spike protein presents to the immune system,” says Lee, who also directs a lab exploring virus structure and dynamics.

“This is something that people in HIV vaccine development have grappled with from the very beginning—this virus mutates and changes itself astronomically and rapidly. Each time it infects an individual, you end up with literally thousands of different variants within that one individual, and if you look across populations, it’s multiplied even more.”

In fact, in February, researchers found an even more deadly strain of circulating in the Netherlands. Luckily, while the strain is a “highly virulent variant,” it still responds to treatment.

“This is just another reminder that these viruses are always changing, so we need scientists to continue studying them,” Zwick says.

Additional coauthors are from the Scripps Research Institute and the University of Washington.

The National Institutes of Health, the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust, a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and a University of Washington Proteomics Resource grant supported the work.

Source: University of Washington