Sediment cores taken from the Southern Ocean dating back 23 million years are providing insight into how ancient methane escaping from the seafloor could have led to climate and environmental changes.

For a new study in Nature Geoscience, oceanographers examined cores—sediment samples from deep parts of the ocean floor—from the Oligocene-Miocene era, roughly 23 million years ago, from areas near Tasmania and Antarctica in the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean.

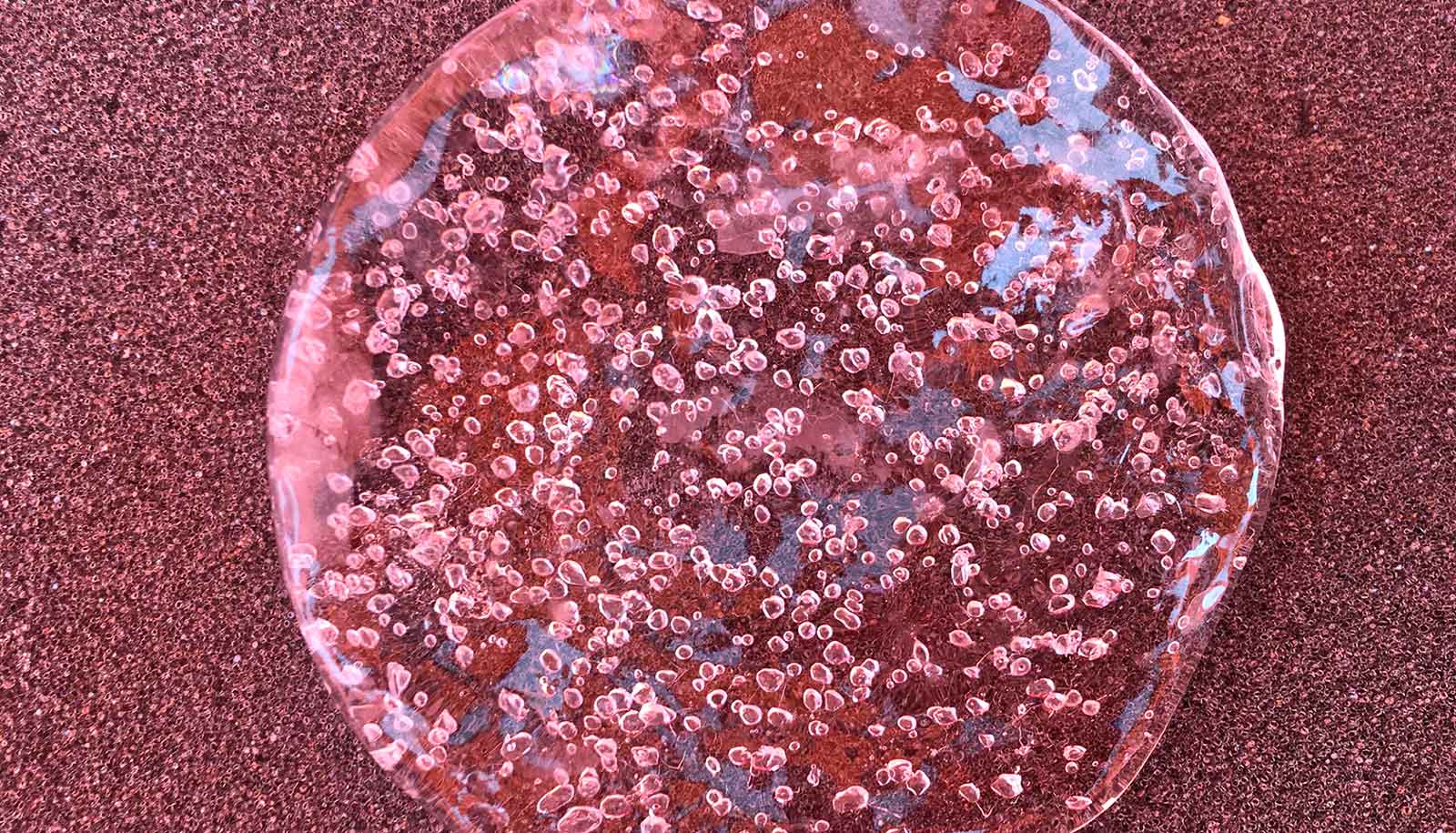

There are billions of tons of carbon stored beneath the ocean floor as gas hydrates—ice-like crystals composed of water and natural gas. Past releases of methane are believed to be related to huge Earth events, such as global warming and subsequent climate shifts.

“For a long time, people thought that methane released from the ocean floor could go into the atmosphere and directly contribute to the greenhouse effect, leading to rapid warming and even mass extinctions,” says Yige Zhang, assistant professor in the oceanography department at Texas A&M University.

“But this idea is no longer popular in the last decade or so because we lack direct evidence of methane release in Earth’s history. Also, modern observations show that even when methane gases are released, they rarely make it to the atmosphere.”

However, Zhang and doctoral student Bumsoo Kim are now able to document past methane release by using markers that consume methane. These “methane-eating” substances are preserved in sediments for tens of millions of years, the researchers say. They could provide direct evidence of methane release from different places in the Southern Ocean.

“We saw that a methane release occurred during a peak glaciation about 23 million years ago,” Zhang says.

Glaciation is the formation, movement, and recession of glaciers, and the process most commonly occurs in Antarctica and Greenland. When large ice sheets form, they draw in a tremendous amount of water that could lower the sea-level by tens to hundreds of feet.

The methane gas release and its after-effects led to ocean acidification and hypoxia (a lack of oxygen in the water), something that was observed after the Deepwater Horizon incident in 2010, when large amounts of methane were released in the Gulf of Mexico, Zhang says.

“One implication of our study is that if gas hydrates start to decompose in the future due to ocean warming, places like the Gulf of Mexico could suffer severely from ocean acidification and expansion of the low oxygen ‘dead zones,'” Kim says.

Texas A&M’s T3 grants and Texas Sea Grant funded the work.

Source: Texas A&M University