A new study establishes live oaks and American sycamores as champions among 17 “super trees” that will help make cities more livable.

The paper also lays out a strategy to improve climate and health in vulnerable urban areas.

The researchers are already implementing their plan in Houston, Texas, and now offer what they’ve learned to others.

The study in the journal Plants People Planet—led by Houston Wilderness President Deborah January-Bevers and colleagues at Rice University and in city government—lays out a three-part framework for deciding which trees to plant, identifying places where planting will have the highest impact, and engaging with community leadership to make the planting project a reality.

Using Houston as a best-case example, the collaborators determined what trees would work best in the city based on their ability to soak up carbon dioxide and other pollutants, drink in water, stabilize the landscape during floods, and provide a canopy to mitigate heat.

With that information, the organizers ultimately identified a site to test their ideas. With cooperation from the city and nonprofit and corporate landowners, they planted 7,500 super trees on several sites near the Clinton Park neighborhood and adjacent to the Houston Ship Channel. (They actually planted 14 species, eliminating those that bear fruit to simplify maintenance for the landowners.) Along with planting native trees, the partners conducted a tree inventory and removed invasive species.

Neighborhood maps

All of that took advance planning, and that’s where statisticians helped narrow the options.

Alumna Laura Campos, a data scientist in the statistics department, was brought into the project by Loren Hopkins, professor in the practice of statistics, environmental analysis at Rice and chief environmental science officer for the city of Houston.

Coauthor Erin Caton of the city’s health department organized data that allowed the team to establish overall rankings for the super trees and their wannabes.

For her part, Campos gathered the wealth of data the university has collected in the past decade linking health and pollution in Houston, creating maps that showed where mass plantings would have the most impact.

“These maps help people understand that their little pocket neighborhoods are connected to the bigger picture,” Campos says. “They help us bring in all the players to get them to realize how everything is interconnected and how public health can benefit with every step forward.”

Oaks, sycamores, and the rest

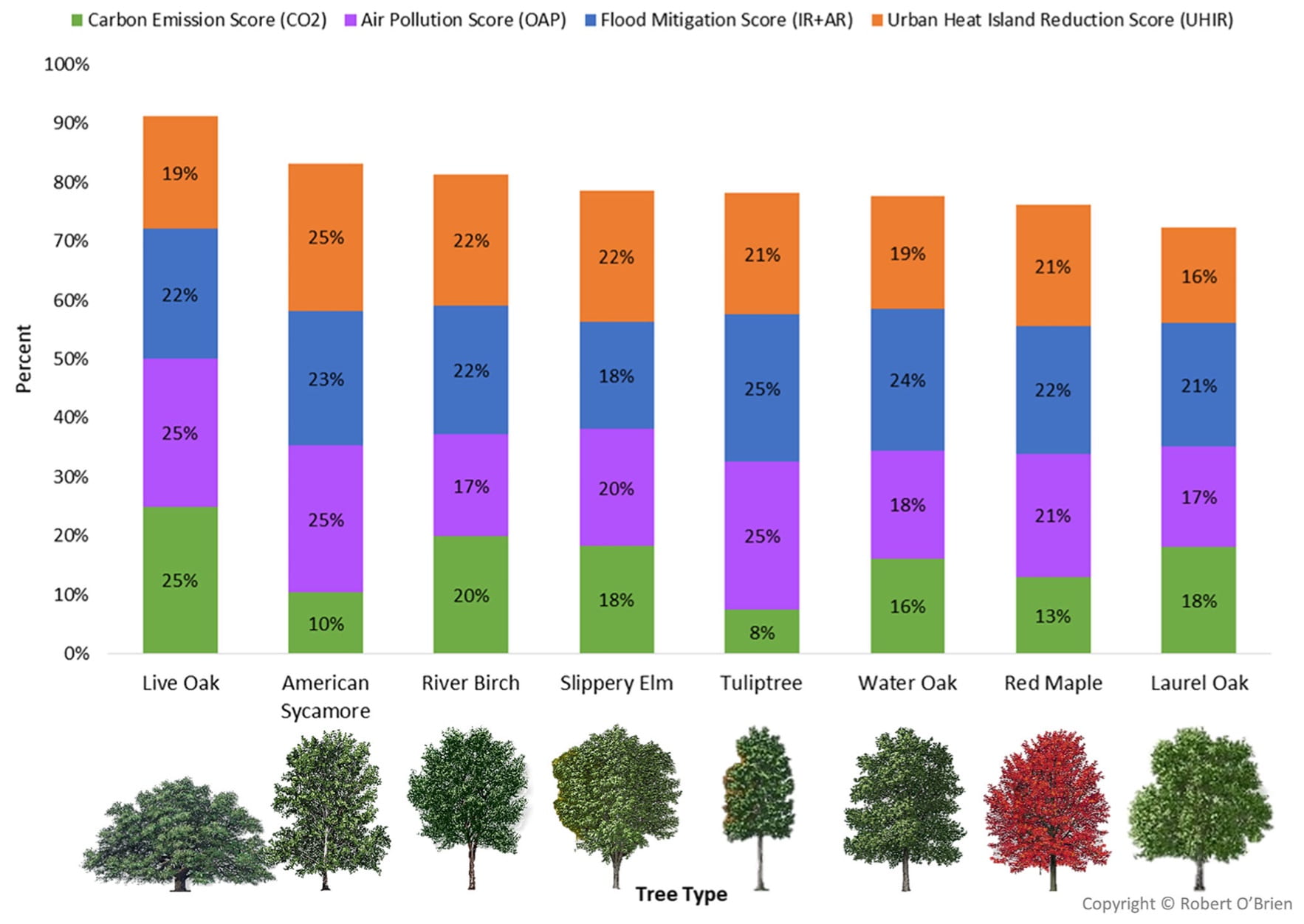

Ranking the species’ talents to soak up pollutants, provide flood mitigation and cool “urban heat islands” helped them eliminate most of the 54 native trees they evaluated. Ultimately, they narrowed the list to 17 super trees, with live oak and American sycamore on top.

Live oaks were No. 1 for their ability to soak up pollutants across the board. The No. 2 sycamore was less able to pull in carbon but excelled at grabbing other pollutants, flood remediation, and reducing heat on the ground with its wide canopy.

The study addresses how such strategic groves can contribute to human health initiatives and took into account an earlier study by Campos, Hopkins, and Katherine Ensor, statistics professor, that established how pollution in Houston causes preventable asthma attacks in schoolchildren. That and another study with the city linking Houston ozone levels to cardiac arrests helped the tree team make its case for the project.

“They took their health care data and overlapped it with our section map, and it was really compelling,” January-Bevers says. “That’s what we wanted to concentrate on first because these are areas right up against plants along the ship channel.”

Some super trees—particularly live oak, American sycamore, red maple, and laurel oak—are adept at pulling ozone, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and particular matter 2.5 microns and smaller from the air. That helps determine where they can be deployed to have maximum impact on neighborhood health.

“We’re still running the program, with over 15,000 native super trees now planted along the ship channel, and it’s incredibly popular,” January-Bevers says, crediting Hopkins with the push to issue a study that could help other communities. “It’s benefiting our city in regions that are critical for air quality, water absorption, and carbon sequestration.”

Source: Rice University