New research documents major differences in potential family caregiver availability by the gender, race, ethnicity, education level, and family structure of the person with dementia.

The study offers stark statistics about a reality that 6 million Americans with dementia and their families live every day: one where people with dementia receive hundreds of hours a month in unpaid care from spouses, adult children, and other relatives, and where some rely on paid help including nursing home care.

People with dementia who are women, Black, low-income, or have lower levels of education are all less likely than their counterparts to have available spouse caregivers, but more likely to have adult children available to provide care, the study finds.

It also shows that the immediate availability of adult children is directly associated with the chances that a person with dementia will continue to live at home or move to a nursing home.

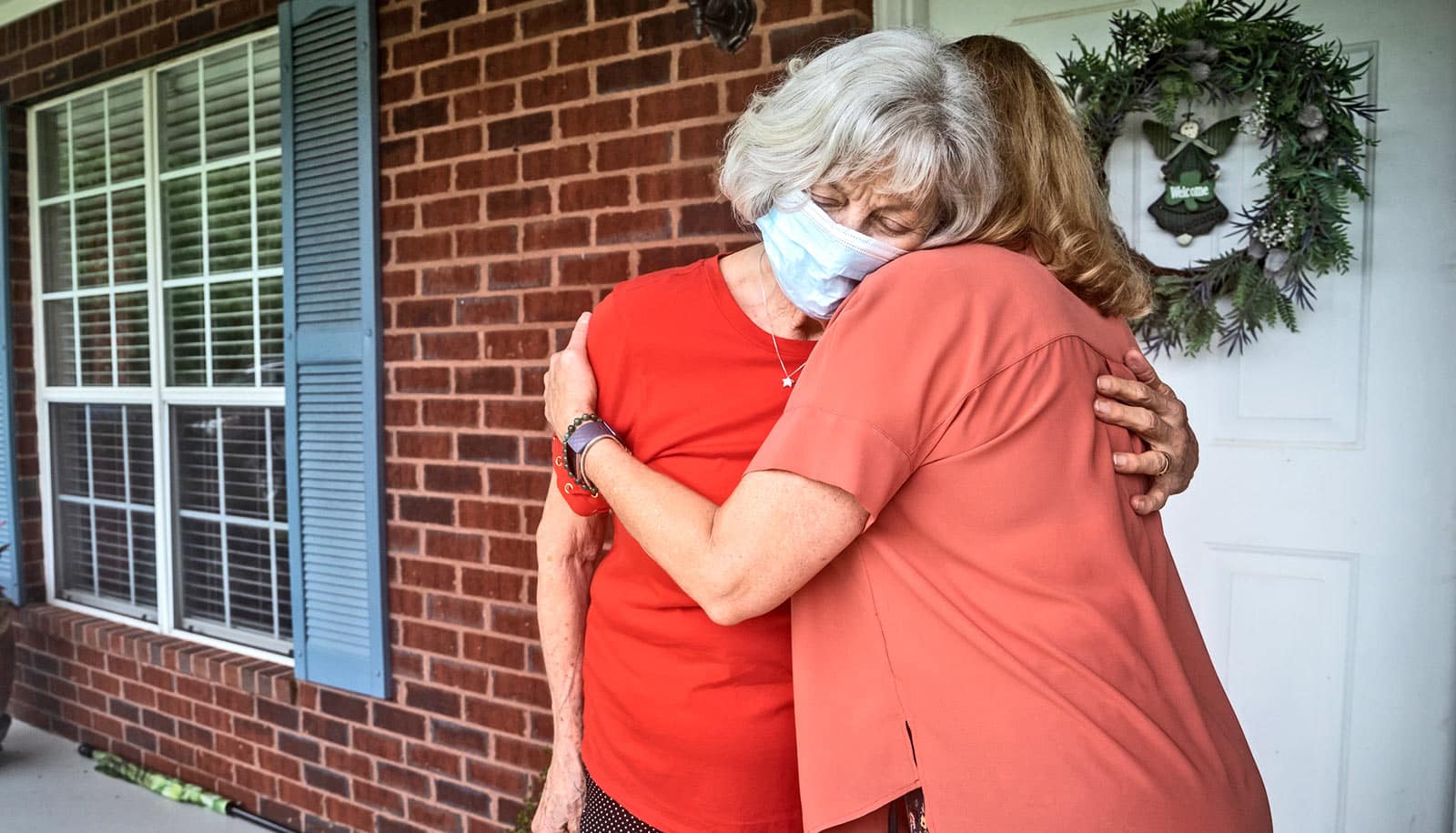

Dementia family caregivers and helpers

Published in the journal Health Affairs, the study draws from comprehensive interviews conducted between 2002 and 2014 with a national sample of nearly 5,000 people with dementia. The data come from the Health and Retirement Study, which is based at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research.

In all, 62% of people with dementia didn’t have a spouse or partner living with them. Another 13% lived with a spouse or partner who needed help with daily living activities themselves. Only 24% lived with a spouse who had no limitations on their abilities.

One-quarter of older adults with dementia lived with an adult child, and an additional 42% had at least one adult child living within 10 miles. But 23% had no adult children living with them or close by.

The study also finds that many adults with dementia receive informal or unpaid care from multiple sources, not just from spouses and adult children but other relatives and friends.

“We know a lot about active caregiving by family members and other unpaid helpers, but we don’t know nearly as much about the potential availability of family members to help people with dementia,” says HwaJung Choi, lead author of the study and a research assistant professor at the University of Michigan Medical School department of internal medicine and the School of Public Health department of health management and policy.

“That’s despite the fact that the availability of family members such as a spouse’s health condition and residential distance to adult children is a significant determinant of what kind of health care people with dementia will use or receive. If they don’t have anyone, the only choice for them as their condition progresses may be full-time nursing home care, which is largely paid for by the Medicaid system.”

The findings of the new study by Choi and colleagues could inform public policy discussions to assess the potential role of family members in providing long-term care for people with dementia, compensate individuals who provide in-home care for relatives, and determine optimal coverage of professional in-home care.

Key findings

Gender: Women with dementia were much more likely than men to have no spouse at home, with 75% of women in this situation compared with 41% of men. Women with spouses were much more likely to have spouses who needed help with their own daily activities. Only 16% of women with dementia live with spouses who are fully capable of taking care of themselves, compared with 38% of men with dementia.

Race and ethnicity: People with dementia who are Black and not Hispanic are least likely to have a spouse; 29% reported having one, compared with 39% of white, non-Hispanic adults and 42% of Hispanic adults with dementia. Hispanic older adults with dementia were much more likely to have an adult child living with them (40%) compared with non-Hispanic whites (18%) and Blacks (31%).

Income and education: Those with the highest levels of education and household wealth were the most likely to have a spouse, and to have a spouse with no limitations. On the other hand, those with higher education or wealth were much less likely to have an adult child living with them.

Dementia plus disability: When the researchers looked at the subgroup that needed help with activities like bathing, dressing, and eating, 19% said they didn’t get any help with these tasks. Another 50% got help from a spouse, adult child, or other unpaid helpers, and 44% got paid help. Spouses provided more hours of help than adult children. However, far more people with dementia and disability received help from adult children (27%) than spouses (18%).

Transition to nursing home: The researchers also looked at adults with dementia who were living in the community at the time of their first interview, and then estimated the odds that they had moved to a nursing home by the follow-up interview two years later. Nearly one-third of those with no adult children were receiving nursing home care by the end of that time, as were one-quarter of those without an adult child living within 10 miles of them. By comparison, 11% of those who had an adult child living with them at the first time point had moved to a nursing home by the end of two years.

“Given the prevalence of dementia and the high cost of in-home and long-term care, finding ways to support family caregivers and better understand the challenges they face is timely and important,” says Cathleen Connell, the senior author of the study and professor in the department of health behavior and health education.

“As we documented, simply having a spouse or a child living nearby isn’t a guarantee that care needs for a family member with dementia can be met. A more nuanced view of family availability is needed to fully appreciate needs, resources, and options over the changing course of this progressive condition.”

Professional paid help

Professional paid help—whether in the home or in a nursing home—may not totally replace the type of care that a family member can provide, Choi says. And studies have shown that the spouses and children of people with dementia place value on being able to provide care for their loved one.

But access to occasional in-home help to give family members respite, or to assist them with the most difficult or physically demanding tasks, can make a big difference, she says. The rest of the time, the live-in family member can provide important monitoring to keep people with dementia safe and comfortable.

“The main point of paid in-home care, or multiple sources of in-home care from other family members and friends, is to alleviate the main caregiver’s burden so they can continue to care for the person with dementia,” Choi says.

This is especially important if the primary caregiver also needs to work for pay; most adult children of people with dementia are in their prime working ages. Their ability to continue working—and their long-term economic opportunity—can be affected by the availability of care resources and paid and unpaid help. Adult children of Black and low-income adults with dementia are probably more affected because of lower spousal availability and limited financial resources among these individuals.

“In addition to its implications for policymakers, our study is an important reminder to clinicians caring for those with dementia to open discussions regarding the extent and availability of family caregivers as early as possible,” says coauthor Kenneth Langa, professor at the University of Michigan Medical School, Institute for Social Research, and Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

“Taking stock of caregiving resources available to patients with dementia before they are needed can help avoid crises, misunderstandings among family members, and hopefully facilitate staying in one’s home for as long as possible.”

Choi says that the current study did not examine the ability of families to afford paid in-home help or to pay for nursing home care. Nor did it look at the health outcomes or total health care costs of the people with dementia based on their family status or use of paid care. That’s what her continued research will look at.

“If we can compensate family helpers for their caregiving and provide the education and training that they need, we can help people with dementia to live in community settings longer, with a higher quality of life, while potentially reducing public spending on nursing home care,” she says.

Source: University of Michigan