In the 20 years since the September 11 terror attacks, four times as many deaths among members of the military have been caused by suicide compared to those killed in action.

That’s 30,177 active duty personnel and veterans of the post-9/11 wars who have taken their own lives.

While these high suicide rates can partially be attributed to the mental health toll of participating in war—exposure to trauma, stress, access to guns, difficulty returning to civilian life after duty—there are additional factors, one of the biggest being traumatic brain injury, unique to the wars stemming from 9/11, that contribute to the rising suicide rates among military members, says Thomas “Ben” Suitt, who earlier this year earned a PhD from Boston University’s graduate program in religion, specializing in the sociology of religion in the military and social ethics.

“Among the demographic of veterans aged 18 to 34, who most likely served in post-9/11 conflicts, the suicide rate per 100,000 was 25.5 in 2005. Today, that rate is 45.9 per 100,000,” Suitt says.

While pursuing his doctorate, Suitt was studying moral injury and the role of faith in 9/11 veterans. Talking with them for his research, he was struck by their stories of trauma.

“I was looking at Veteran Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) data, and I saw that no one had put it in terms of how bad suicide rates are getting,” Suitt says. “Rates are getting worse and worse.”

Historically, he says, data indicate that suicide rates typically go down among members of the military during wars. But military suicides have gone up during the War on Terror, meeting and surpassing the suicide rate among civilians.

Why have military suicides spiked since 9/11?

Suitt decided to look into factors specific to post-9/11 combat that might contribute to the rise. In his findings, published in June, he firstly points out that there’s been an increase in military sexual trauma, which he says can be complexly traumatizing because victims often have to continue working alongside their attacker.

“Military sexual trauma affects 55% of women and 38% of men,” he says. “Seventy-one percent of female veterans are seeking therapy to treat [post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)] from military sexual trauma.”

Suitt says the military’s historically masculine, machismo culture affects how women are received by their peers in the military.

Another rising trend since September 11 has been exposure of soldiers to more and more improvised explosive devices (IEDs), which has led to a significant increase in the number of soldiers and veterans experiencing traumatic brain injuries, known in shorthand as TBIs.

“On one hand, [soldiers] have the stress burden of knowing that [while deployed in combat zones] there are IEDs everywhere,” Suitt says. “Then, people involved in an IED explosion get TBIs—these have become the signature injury of the War on Terror.”

Some soldiers, he says, have experienced between 15 and 20 IED explosions and subsequent brain injuries. “The crazy thing is that because of medical advances, people are surviving [explosions] and being redeployed. You want soldiers to survive—but they are being redeployed so many times, contributing to chronic pain, PTSD, and TBI.”

Those three factors add up to create what’s known as polytrauma, a condition that Suitt says became common among post-9/11 veterans. On top of that, there’s another issue awaiting veterans when they finally do return home to the US.

“What makes the War on Terror unique is that a poll in 2018 showed that 42% of voting Americans didn’t know we were still at war,” Suitt says. Although the recent US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan helped thrust the war back into the spotlight, he says veterans of post-9/11 wars have for the most part been returning home to a disinterested public.

Moral injury

To help prevent military suicides, Suitt says focusing on how to better receive veterans back into civilian communities is a good place to focus energies.

“Civilians should really care,” he says, “and the first step is inviting veterans to talk with you, building relationships with them, and actively making sure that veterans are invited to be a part of the community.”

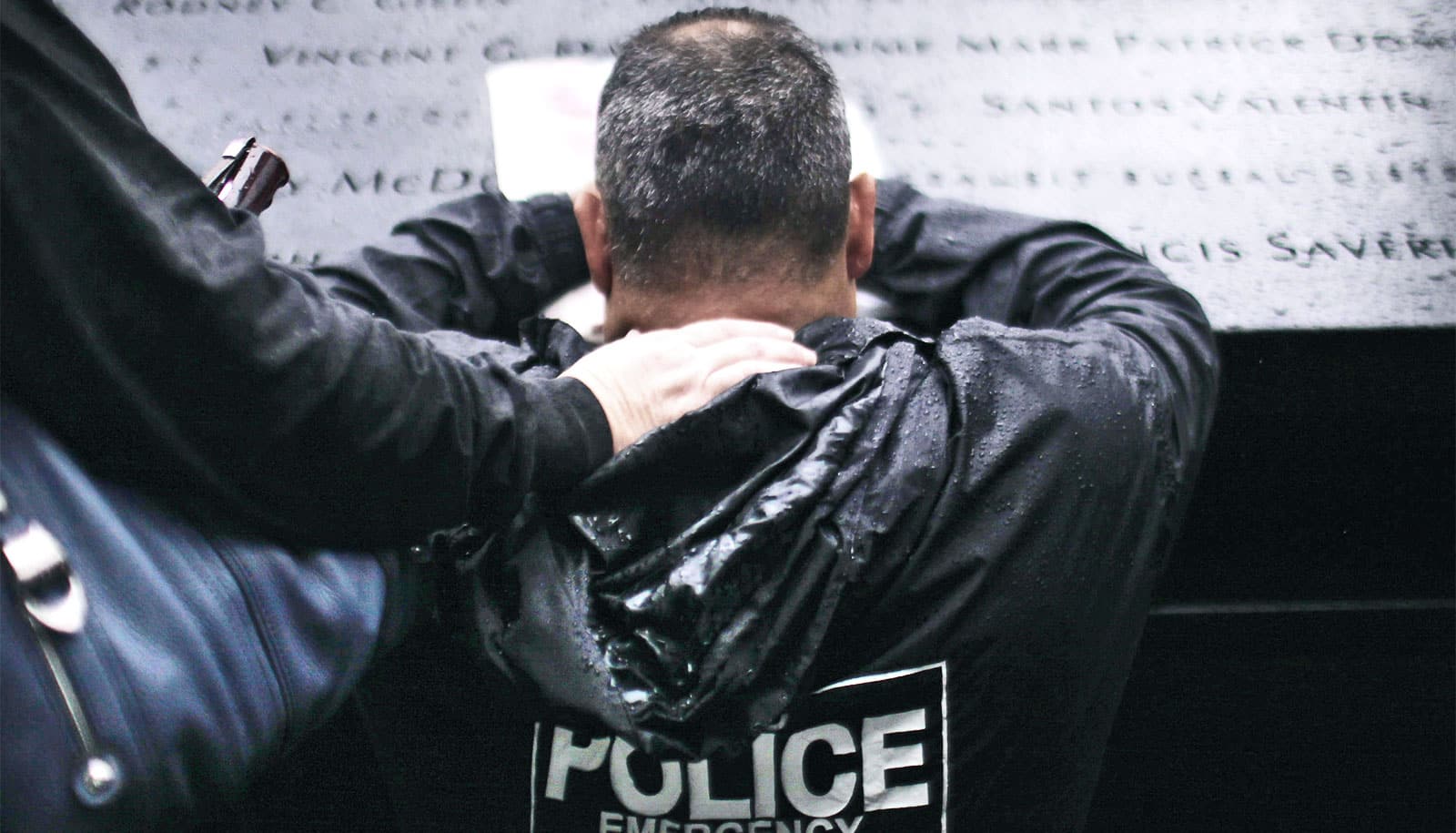

That reintegration into civilian life—and acknowledgment from the public of what veterans have been through—could help to counterbalance the effects of moral injury.

Suitt says the term “moral injury” was first coined in the 1990s by a psychologist who worked with Vietnam veterans. What they described wasn’t PTSD, but a sense of betrayal by their higher-ups, the government—or, in a religious sense, divine betrayal by a higher power.

“They thought God would protect them, or their best friend, but when terrible experiences happen or your best friend gets killed, it destroys their sense of faith and goodness in the world,” Suitt says.

Veterans can also feel a sense of injury from the perpetration of killing someone in combat, and then they may no longer view themselves as good people, which makes it so that they can’t participate in their communities or continue living their lives, as their sense of self has been destroyed.

“I recently spoke with a veteran who experienced moral injury because he witnessed enemy forces killing women and children,” Suitt says. “If he and his troops were forced to make difficult choices as a result of that? At its simplest, it’s a betrayal of what’s right—a rupture in your self-narrative that you’re a good person.”

Preventive, not reactionary action

The military relies heavily on their chaplains to do a lot of counseling, but Suitt believes those efforts could be bolstered by incorporating social workers and mental health counselors more holistically into debriefing troops after combat missions.

As much as Suitt says he does not want to be critical of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, he does want to hold the government to task, to make sure they are doing everything in their power to take care of troops. He spoke directly with the head of suicide prevention at the VA, a conversation in which they discussed the VA’s new campaign focused on gun prudence and safety, based on an idea of creating a large triangle between guns, ammunition, and a veteran who may be struggling with suicidal ideation.

“You want to increase the lengths of the legs between those triangles,” Suitt says, which could mean removing guns from the house, or keeping guns in a locked safe with ammunition stored separately.

Above all, Suitt wants to raise awareness about the new challenges that the post-9/11 wars have presented to American troops, and to crush stereotypes that prevent progress being made in caring for veterans’ mental health.

“There’s a prevailing stereotype that veterans are simultaneously heroes and broken people because of the traumatic experiences they have endure—which makes it easy to conclude, oh, well of course suicide rates are bad among veterans,” he says.

That’s why, he says, military leadership needs to bake today’s new research and resources around suicide prevention into military culture.

“If [soldiers] are going to clean their weapons and take care of their physical health, then their mental health has to be a primary factor too. We have to be preventative, not reactionary,” he says.

Source: Boston University