Older adults with more “bad” than “good” bacteria in their gums are more likely to have evidence for amyloid beta—a key biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease—in their cerebrospinal fluid, according to a new study.

However, this imbalance in oral bacteria was not associated with another Alzheimer’s biomarker called tau.

The study, published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, adds to the growing evidence of a connection between periodontal disease (gum disease) and Alzheimer’s. Periodontal disease—which affects 70% of adults 65 and older, according to CDC estimates—is characterized by chronic and systemic inflammation, with pockets between the teeth and gums enlarging and harboring bacteria.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study showing an association between the imbalanced bacterial community found under the gumline and a CSF biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease in cognitively normal older adults,” says Angela Kamer, associate professor of periodontology and implant dentistry at New York University College of Dentistry and the study’s lead author.

“The mouth is home to both harmful bacteria that promote inflammation and healthy, protective bacteria. We found that having evidence for brain amyloid was associated with increased harmful and decreased beneficial bacteria.”

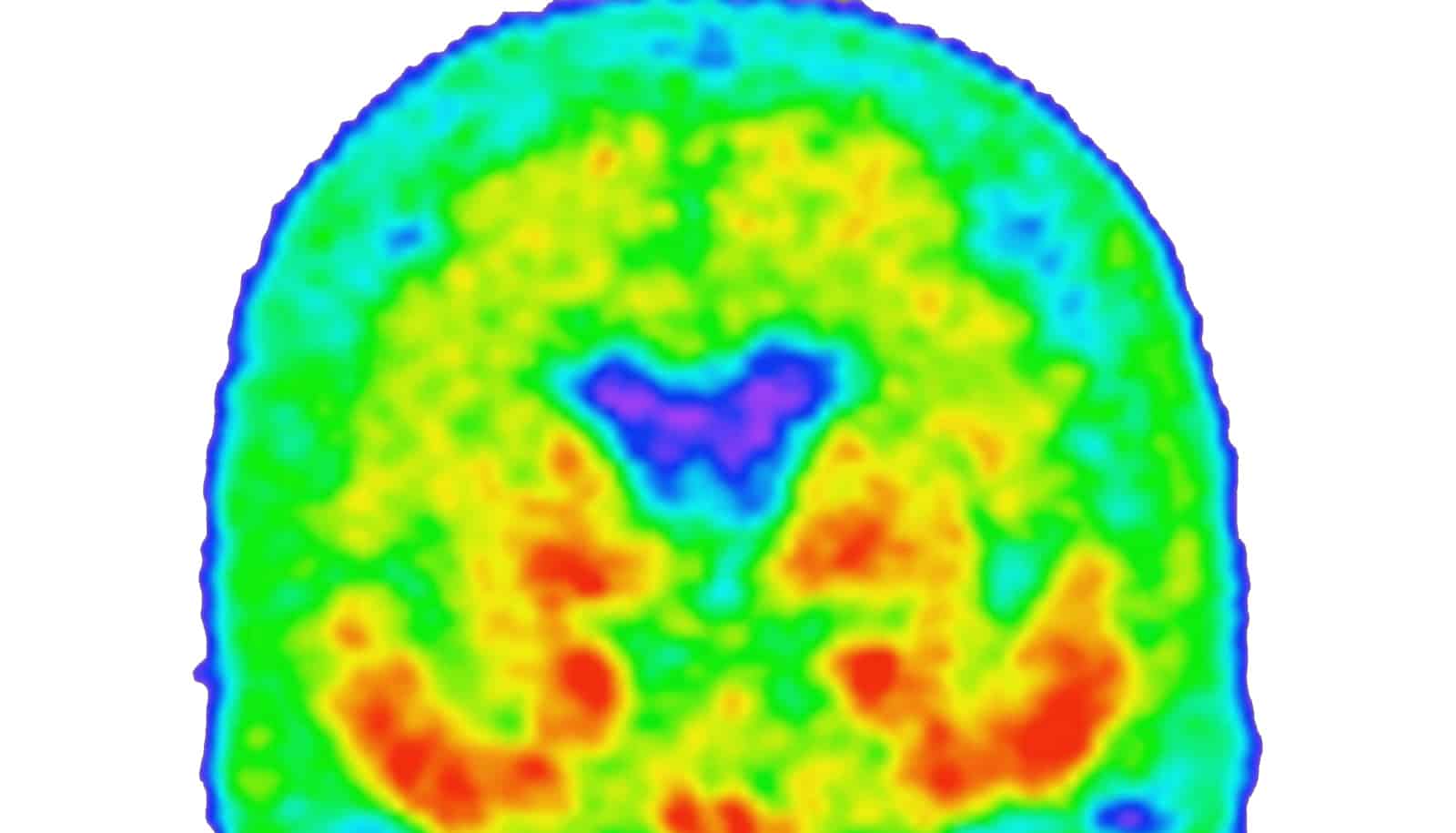

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by two hallmark proteins in the brain: amyloid beta, which clumps together to form plaques and is believed to be the first protein deposited in the brain as Alzheimer’s develops, and tau, which builds up in nerve cells and forms tangles.

“The mechanisms by which levels of brain amyloid accumulate and are associated with Alzheimer’s pathology are complex and only partially understood. The present study adds support to the understanding that proinflammatory diseases disrupt the clearance of amyloid from the brain, as retention of amyloid in the brain can be estimated from CSF levels,” says senior author Mony J. de Leon, professor of neuroscience in radiology and director of the Brain Health Imaging Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Amyloid changes are often observed decades before tau pathology or the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease are detected.”

The researchers studied 48 healthy, cognitively normal adults ages 65 and older. Participants underwent oral examinations to collect bacterial samples from under the gumline, and lumbar puncture was used to obtain CSF in order to determine the levels of amyloid beta and tau. To estimate the brain’s expression of Alzheimer’s proteins, the researchers looked for lower levels of amyloid beta (which translate to higher brain amyloid levels) and higher levels of tau (which reflect higher brain tangle accumulations) in the CSF.

Analyzing the bacterial DNA of the samples taken from beneath the gumline under the guidance of College of Dentistry microbiologist Deepak Saxena, the researchers quantified bacteria known to be harmful to oral health (e.g., Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Fretibacterium) and pro-oral health bacteria (e.g. Corynebacterium, Actinomyces, Capnocytophaga).

The results showed that individuals with an imbalance in bacteria, with a ratio favoring harmful to healthy bacteria, were more likely to have the Alzheimer’s signature of reduced CSF amyloid levels. The researchers hypothesize that because high levels of healthy bacteria help maintain bacterial balance and decrease inflammation, they may be protective against Alzheimer’s.

“Our results show the importance of the overall oral microbiome—not only of the role of ‘bad’ bacteria, but also ‘good’ bacteria—in modulating amyloid levels,” says Kamer. “These findings suggest that multiple oral bacteria are involved in the expression of amyloid lesions.”

The researchers did not find an association between gum bacteria and tau levels in this study, so it remains unknown whether tau lesions will develop later or if the subjects will develop the symptoms of Alzheimer’s. The researchers plan to conduct a longitudinal study and a clinical trial to test if improving gum health—through “deep cleanings” to remove deposits of plaque and tartar from under the gumline—can modify brain amyloid and prevent Alzheimer’s disease.

Additional coauthors are from NYU, Weill Cornell Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, the University of Gothenburg, Sahlgrenska University, and University College London.

Funding for the study came from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, as well as the Alzheimer’s Association.

Source: New York University