Fundamental particles called muons behave in a way that scientists’ best theory to date, the Standard Model of particle physics, doesn’t predict, researchers report.

The finding comes from the first results from the Muon g-2 experiment at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

“This experiment is a bit like a detective story.”

This landmark result confirms a discrepancy that has been gnawing at researchers for decades.

The strong evidence that muons deviate from the Standard Model calculation might hint at exciting new physics. The muons in this experiment act as a window into the subatomic world and could be interacting with yet-undiscovered particles or forces.

“This experiment is a bit like a detective story,” says team member David Hertzog, a University of Washington professor of physics and a founding spokesperson of the experiment. “We have analyzed data from the Muon g-2’s inaugural run at Fermilab, and discovered that the Standard Model alone cannot explain what we’ve found. Something else, perhaps beyond the Standard Model, may be required.”

A muon is about 200 times as massive as its cousin, the electron. They occur naturally when cosmic rays strike Earth’s atmosphere. Particle accelerators at Fermilab can produce them in large numbers. Like electrons, muons act as if they have a tiny internal magnet. In a strong magnetic field, the direction of the muon’s magnet precesses, or “wobbles,” much like the axis of a spinning top. The strength of the internal magnet determines the rate that the muon precesses in an external magnetic field and is described by a number known as the g-factor. This number can be calculated with ultra-high precision.

As the muons circulate in the Muon g-2 magnet, they also interact with a “quantum foam” of subatomic particles popping in and out of existence. Interactions with these short-lived particles affect the value of the g-factor, causing the muons’ precession to speed up or slow down slightly. The Standard Model predicts with high precision what the value of this so-called “anomalous magnetic moment” should be. But if the quantum foam contains additional forces or particles not accounted for by the Standard Model, that would tweak the muon g-factor further.

Hertzog, then at the University of Illinois, was one of the lead scientists on the predecessor experiment at Brookhaven National Laboratory. That endeavor concluded in 2001 and offered hints that the muon’s behavior disagreed with the Standard Model. The new measurement from the Muon g-2 experiment at Fermilab strongly agrees with the value found at Brookhaven and diverges from theory with the most precise measurement to date.

The accepted theoretical values for the muon are:

- g-factor: 2.00233183620(86)

- anomalous magnetic moment: 0.00116591810(43)

The new experimental world-average results announced by the Muon g-2 collaboration today are:

- g-factor: 2.00233184122(82)

- anomalous magnetic moment: 0.00116592061(41)

The combined results from Fermilab and Brookhaven show a difference with theoretical predictions at a significance of 4.2 sigma, a little shy of the 5 sigma—or 5 standard deviations—that scientists prefer as a claim of discovery. But it is still compelling evidence of new physics. The chance that the results are a statistical fluctuation is about 1 in 40,000.

“This result from the first run of the Fermilab Muon g-2 experiment is arguably the most highly anticipated result in particle physics over the last years,” says Martin Hoferichter, an assistant professor at the University of Bern and member of the theory collaboration that predicted the Standard Model value. “After almost a decade, it is great to see this huge effort finally coming to fruition.”

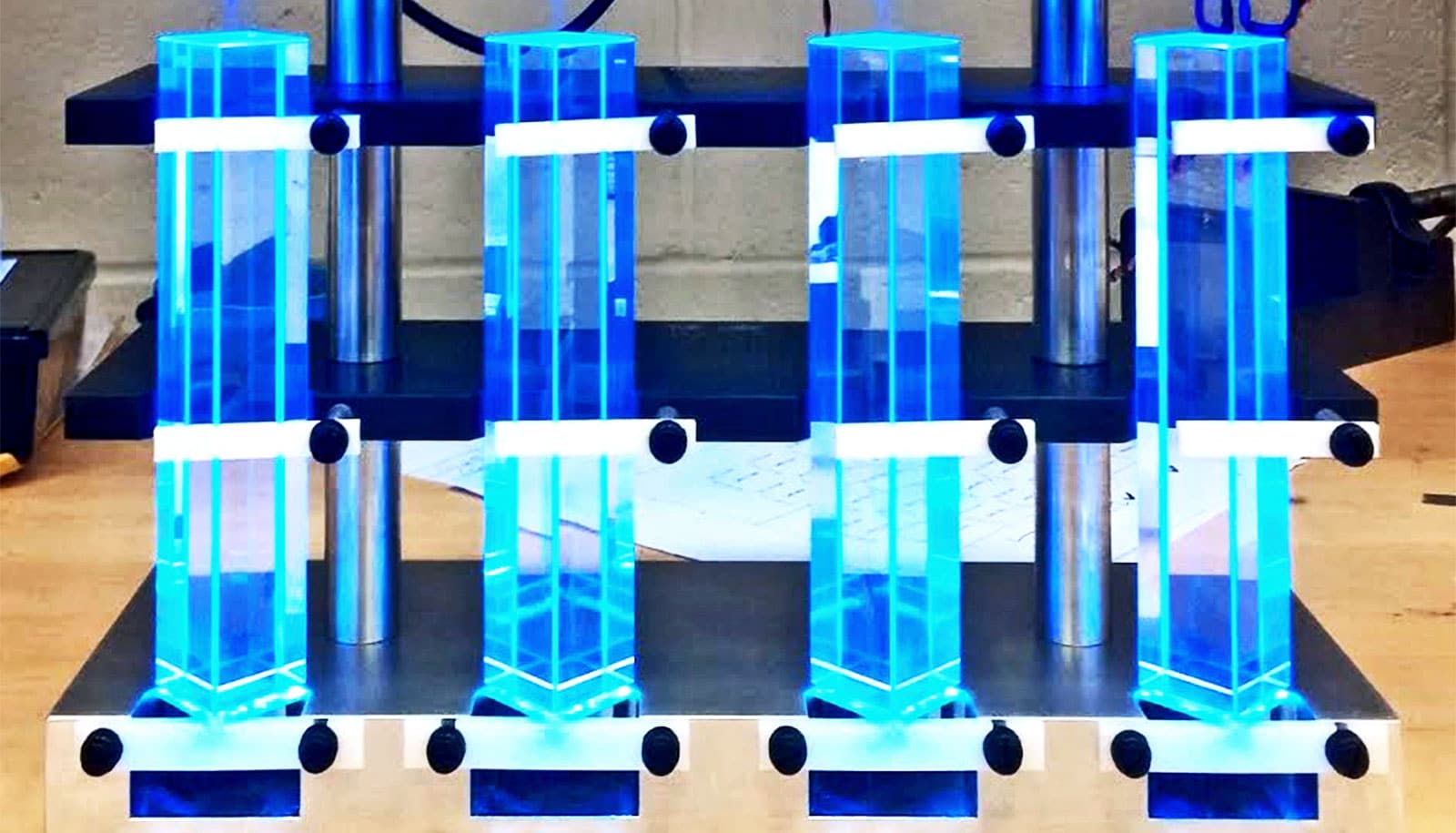

The Fermilab experiment, which is ongoing, reuses the main component from the Brookhaven experiment, a 50-foot-diameter superconducting magnetic storage ring. In 2013, it was transported 3,200 miles by land and sea from Long Island to the Chicago suburbs, where scientists could take advantage of Fermilab’s particle accelerator and produce the most intense beam of muons in the United States. Over the next four years, researchers assembled the experiment; tuned and calibrated an incredibly uniform magnetic field; developed new techniques, instrumentation, and simulations; and thoroughly tested the entire system.

The Muon g-2 experiment sends a beam of muons into the storage ring, where they circulate thousands of times at nearly the speed of light. Detectors lining the ring allow scientists to determine how fast the muons are “wobbling.”

Many of the sensors and detectors at Fermilab were constructed at the University of Washington, such as instruments to measure the muon beam as it enters the storage ring and to detect the telltale particles that arise when muons decay. Dozens of scientists—including faculty, postdoctoral researchers, technicians, graduate students, and undergraduate students—have worked to assemble these sensitive instruments and then install and monitor them at Fermilab.

“The prospects of the new result triggered a coordinated theory effort to provide our experimental colleagues with a robust, consensus Standard-Model prediction,” says Hoferichter. “Future runs will motivate further improvements, to allow for a conclusive statement if physics beyond the Standard Model is lurking in the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon.”

In its first year of operation, in 2018, the Fermilab experiment collected more data than all prior muon g-factor experiments combined. The Muon g-2 collaboration has now finished analyzing the motion of more than 8 billion muons from that first run.

Data analysis on the second and third runs of the experiment is under way; the fourth run is ongoing, and a fifth run is planned. Combining the results from all five runs will give scientists an even more precise measurement of the muon’s “wobble,” revealing with greater certainty whether new physics is hiding within the quantum foam.

“So far we have analyzed less than 6% of the data that the experiment will eventually collect,” says Fermilab scientist Chris Polly, who is a co-spokesperson for the current experiment and was a lead University of Illinois graduate student under Hertzog during the Brookhaven experiment. “Although these first results are telling us that there is an intriguing difference with the Standard Model, we will learn much more in the next couple of years.”

“With these exciting results our team, in particular our students, is enthusiastic to push hard on the remaining data analysis and future data-taking in order to realize our ultimate precision goal,” says Peter Kammel, research professor of physics at the University of Washington.

A paper on the research appears in Physical Review Letters. Hertzog will present the results at a University of Washington Department of Physics colloquium on April 12.

The Muon g-2 experiment is an international collaboration between Fermilab in Illinois and more than 200 scientists from 35 institutions in seven countries.

Source: University of Washington