Since the start of the pandemic, there have been more than 492,000 documented cases of COVID-19 among inmates and staff in US prisons, jails, and detention centers, according to the COVID Prison Project.

That’s nearly as many cases as in the entire state of Minnesota.

Further, there have been more than 2,500 deaths due to the coronavirus.

As high as they are, these numbers are likely an undercount of infections in settings where crowding makes it easy for the virus to spread and inadequate health care leaves populations especially vulnerable, says Homer Venters, an adjunct clinical associate professor at the School of Global Public Health New York University.

Some of these COVID-19 are the latest example of “jail-attributable deaths,” a term Venters coined for cases in which a death can be linked to care or conditions behind bars—for instance, not providing insulin to an incarcerated person with diabetes.

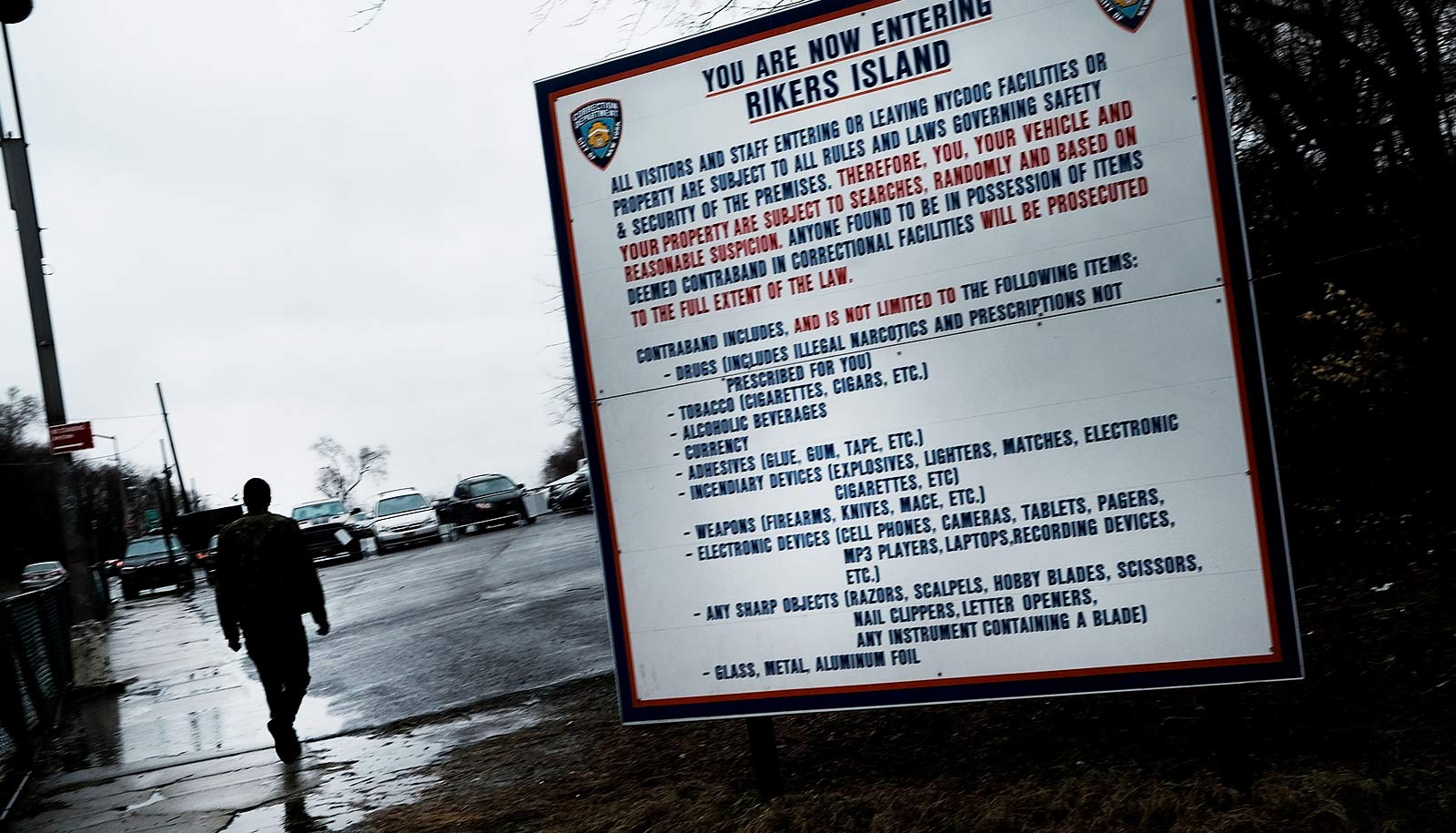

A physician and epidemiologist, Venters previously served as the chief medical officer for New York City’s correctional health services. Over the past year, he has focused on addressing COVID-19 responses in jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers, reviewing policies and procedures and conducting in-person inspections of more than 20 facilities across the country.

Last month, Venters was appointed to the Biden-Harris COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force. The mandate of the task force, led by Marcella Nunez-Smith at Yale University, is to help ensure an equitable response to the pandemic.

“For my part, I am eager to contribute perspective about how devastating COVID-19 has been behind bars and promote some evidence-based solutions,” says Venters. “The conditions I have seen in COVID-19 responses across the nation represent a stark example of racial disparities in health care and outcomes from COVID-19.”

Here, Venters discusses the disproportionate impact COVID-19 has had on incarcerated people and how it has exacerbated existing health challenges in these settings (Note: His comments are his own and do not represent official task force positions):

You recognized in early 2020—before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic—that the virus was going to be disastrous for people behind bars. Why are detention settings so vulnerable to COVID-19?

I think most of us can recognize how the physical confines of detention settings promote the spread of COVID-19, but there are two other crucial elements to how devastating these outbreaks are.

One is the manner in which we have filled carceral settings with high-risk people, those with physical and behavioral health problems, and people who are older. The second is that health care systems in these facilities are often substandard, and that access to emergency care, as well as basic care for chronic health problems fails to meet minimum standards that we would expect in community settings. These failures resulted in poor care before COVID-19 developed as well as inadequate responses to new COVID-19 infections.

What are the top three policies that need to be in place to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in these settings?

I would prioritize release, vaccination, and independent auditing. The first involves working to identify high-risk people who are close to release dates or otherwise can be released without public safety concerns. This decreases their risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19, as well as increasing the ability of facilities to manage outbreaks.

Vaccination involves prioritizing these settings and properly treating them like other congregate settings, but also involves working with credible messengers to promote vaccine acceptance.

And independent auditing involves creating an official role for the CDC and state departments of health in measuring how well carceral settings are doing with these complex tasks, not leaving the assessment of adequacy up to them to report. This should include measuring whether and how facilities are implementing CDC guidelines and assessing whether deaths from COVID-19 related illness reflect systemic deficiencies in facility responses.

What are the challenges of vaccinating people in correctional settings? In many places we’ve seen a lack of political will to allocate vaccines to incarcerated people. But is vaccine hesitancy also an issue among this population?

Regarding access, some states haven’t even mentioned where incarcerated people fall on their list of priorities, and given that these are congregate settings, with many high-risk people, we need to prioritize them just as we would other congregate settings.

We also have major work to do promoting engagement and this requires partnering with credible messengers, including currently and formerly detained people who can work to promote the safety and benefit of vaccines.

The mistrust of correctional health services is well-founded in many settings; imagine the health service that cleared you to go into solitary confinement or turned a blind eye to physical or sexual abuse now approaching you to take a new vaccine. This divide can be navigated by relying on these credible messengers. This is happening in a few settings, but it requires resources, training, and staff.

What have we learned from COVID-19 that should be carried forward to improve health in detention settings beyond the pandemic?

My hope is that we can leverage the involvement of our public health agencies in COVID-19 behind bars to create lasting changes. First, we need to be honest about the health risks of incarceration. Going to jail, prison, and immigration detention brings health risks to people, and the thousands of COVID-19 deaths among detained people provide a devastating example of this truth.

Source: NYU