Researchers have created an aerogel that extracts water from air without any external power source.

In the Earth’s atmosphere, there is water that can fill almost half a trillion Olympic swimming pools. But it has long been overlooked as a source for drinking water.

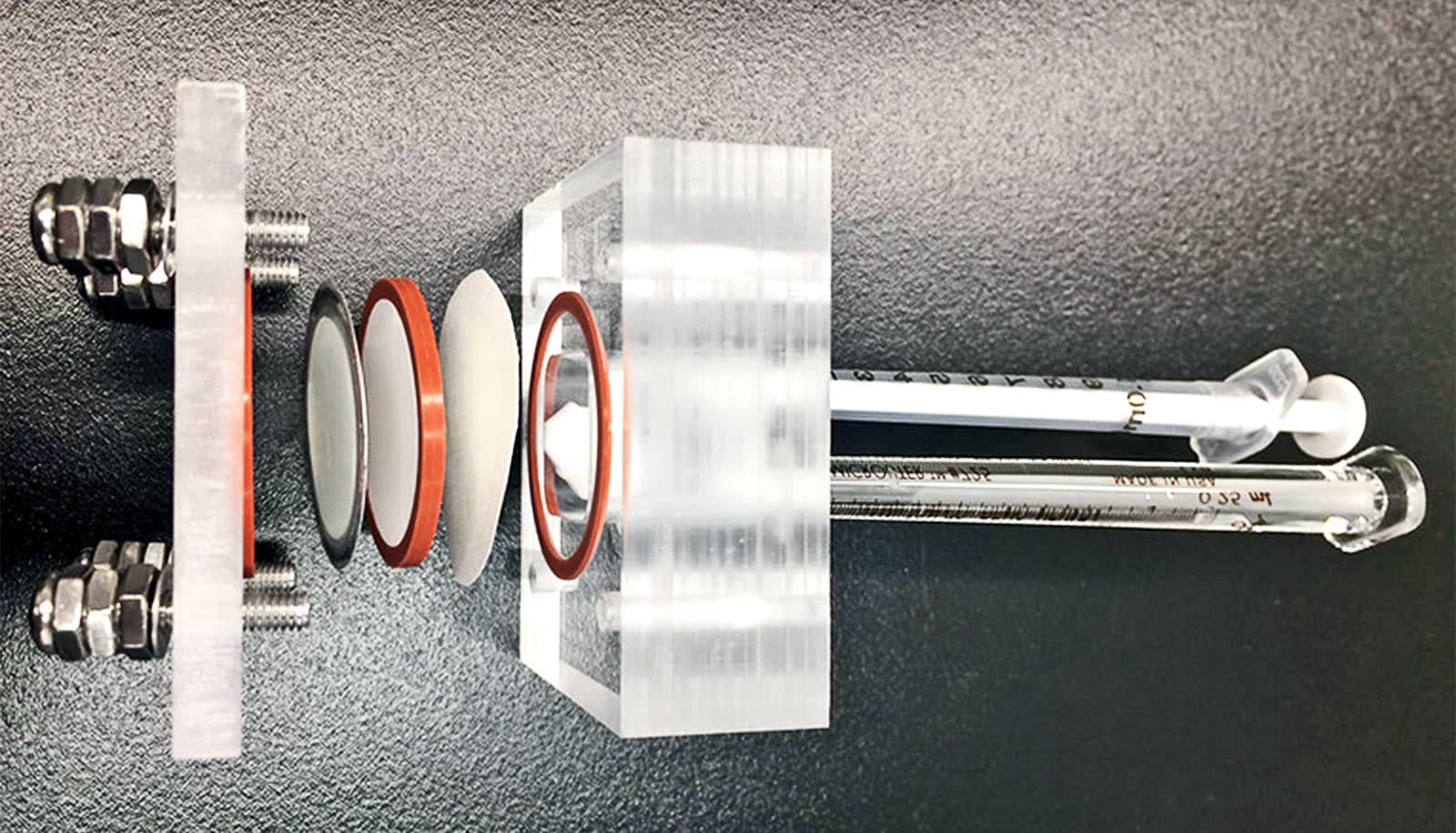

To extract water from this underutilized source, the researchers created a type of aerogel, a solid material that weighs almost nothing. Under the microscope, it looks like a sponge, but it does not have to be squeezed to release the water it absorbs from the air. It also does not need a battery. In a humid environment, one kilogram (2.2 lbs.) of it will produce 17 liters (4.5 gallons) of water a day.

The trick is in the long, snakelike molecules, known as polymers, building up the aerogel. The special long-chain polymer consists of a sophisticated chemical structure that can continuously switch between attracting water and repelling water.

The “smart” aerogel autonomously gathers water molecules from the air, condenses them into a liquid, and releases the water. When there is sunshine, the smart structure can further boost the water release by transitioning to a complete water-hating state. And it’s very good at what it does: 95% of the water vapor that goes into the aerogel comes out as water. In laboratory tests, the aerogel gave water non-stop for months.

The researchers tested the water and found that it met World Health Organization’s standards for drinking water.

Other scientists have previously devised ways to extract water from air, but their designs had to be powered by sunlight or electricity, and had moving parts that had to be opened and closed.

A paper about the aerogel appears in the journal Science Advances.

The researchers are now looking for industry partners to scale it up for domestic or industrial use. It could, for example, find a place in endurance sports or survival kits.

“Given that atmospheric water is continuously replenished by the global hydrological cycle, our invention offers a promising solution for achieving sustainable freshwater production in a variety of climatic conditions, at minimal energy cost,” says Ho Ghim Wei, a professor in electrical and computer engineering department at the National University of Singapore, who led the research.

Source: National University of Singapore