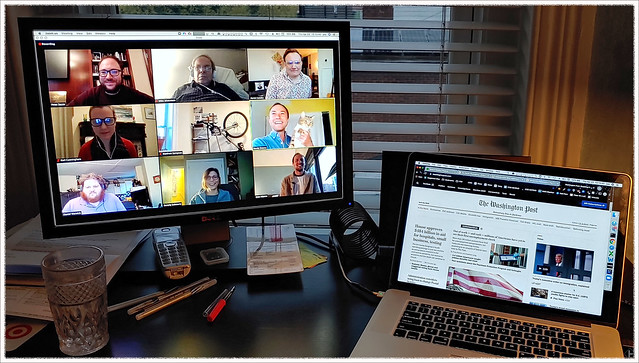

Leaving your camera off during a virtual meeting can do a lot to reduce your carbon footprint, a new study shows.

The study says that despite a record drop in global carbon emissions in 2020, a pandemic-driven shift to remote work and more at-home entertainment still has significant environmental impact due to how internet data is stored and transferred around the world.

Just one hour of videoconferencing or streaming, for example, emits 150-1,000 grams of carbon dioxide (a gallon of gasoline burned from a car emits about 8,887 grams), requires 2-12 liters of water, and demands a land area adding up to about the size of an iPad Mini.

Leaving your camera off during a web call can reduce these footprints by 96%. Streaming content in standard definition rather than in high definition while using apps such as Netflix or Hulu also could bring an 86% reduction, researchers estimate.

The study, published in the journal Resources, Conservation & Recycling, is the first to analyze the water and land footprints associated with internet infrastructure in addition to carbon footprints.

“If you just focus on one type of footprint, you miss out on others that can provide a more holistic look at environmental impact,” says Roshanak “Roshi” Nateghi, a professor of industrial engineering at Purdue University, whose work looks to uncover gaps and assumptions in energy research that have led to underestimating the effects of climate change.

300,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools

A number of countries have reported at least a 20% increase in internet traffic since March. If the trend continues through the end of 2021, this increased internet use alone would require a forest of about 71,600 square miles—twice the land area of Indiana—to sequester the emitted carbon, the study shows.

The additional water needed in the processing and transmission of data would also be enough to fill more than 300,000 Olympic-size swimming pools, while the resulting land footprint would be about equal to the size of Los Angeles.

The team estimates the carbon, water, and land footprints associated with each gigabyte of data used in YouTube, Zoom, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and 12 other platforms, as well as in online gaming and miscellaneous web surfing. As expected, the more video used in an application, the larger the footprints.

Because data processing uses a lot of electricity, and any production of electricity has carbon, water, and land footprints, reducing data download reduces environmental damage.

“Banking systems tell you the positive environmental impact of going paperless, but no one tells you the benefit of turning off your camera or reducing your streaming quality. So without your consent, these platforms are increasing your environmental footprint,” says Kaveh Madani, who led and directed the current study as a visiting fellow at the Yale University MacMillan Center.

Water and land footprints

The internet’s carbon footprint had already been increasing before COVID-19 lockdowns, accounting for about 3.7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. But the water and land footprints of internet infrastructure have largely been overlooked in studies of how internet use impacts the environment, he says.

Madani teamed up with Nateghi’s research group to investigate these footprints and how increased internet traffic might affect them, finding that the footprints not only vary by web platform, but also by country.

The team gathered data for Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Iran, Japan, Mexico, Pakistan, Russia, South Africa, the UK, and the US. Processing and transmitting internet data in the US, the researchers found, has a carbon footprint that is 9% higher than the world median, but water and land footprints that are 45% and 58% lower, respectively.

Incorporating the water and land footprints of internet infrastructure painted a surprising picture for a few countries. Even though Germany, a world renewable energy leader, has a carbon footprint well below the world median, its water and land footprints are much higher. The country’s energy production land footprint, for example, is 204% above the median, the researchers calculate.

Purdue graduate students Renee Obringer, Benjamin Rachunok, and Debora Maia-Silva performed the calculations and data analysis in collaboration with Maryam Arbabzadeh, a postdoctoral research associate at MIT. The estimates are based on publicly available data for each platform and country, models developed by Madani’s research group, and known values of energy use per gigabyte of fixed-line internet use.

The estimates are rough, the researchers say, since they’re only as good as the data service providers and third parties made available. But the team believes that the estimates still help to document a trend and bring a more comprehensive understanding of environmental footprints associated with internet use.

“These are the best estimates given the available data. In view of these reported surges, there is a hope now for higher transparency to guide policy,” Nateghi says.

Additional researchers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Yale, and Purdue contributed to the study. The Purdue Climate Change Research Center, the Purdue Center for the Environment, the MIT Energy Initiative, and the Yale MacMillan Center supported the work.

Source: Purdue University