The mystery surrounding the whereabouts of a supermassive black hole has deepened, researchers say.

Despite searching with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have no evidence that a distant black hole estimated to weigh between 3 billion and 100 billion times the mass of the sun is anywhere to be found.

This missing black hole should be in the enormous galaxy in the center of the galaxy cluster Abell 2261, which is located about 2.7 billion light-years from Earth.

Nearly every large galaxy in the universe contains a supermassive black hole in their center, with a mass that is millions or billions of times that of the sun.

Since the mass of a central black hole usually tracks with the mass of the galaxy itself, astronomers expect the galaxy in the center of Abell 2261 to contain a supermassive black hole that rivals the heft of some of the largest known black holes in the universe.

Using Chandra data obtained in 1999 and 2004, astronomers had already searched the center of Abell 2261’s large central galaxy for signs of a supermassive black hole. They looked for material that has been superheated as it fell towards the black hole and produced X-rays, but did not detect such a source.

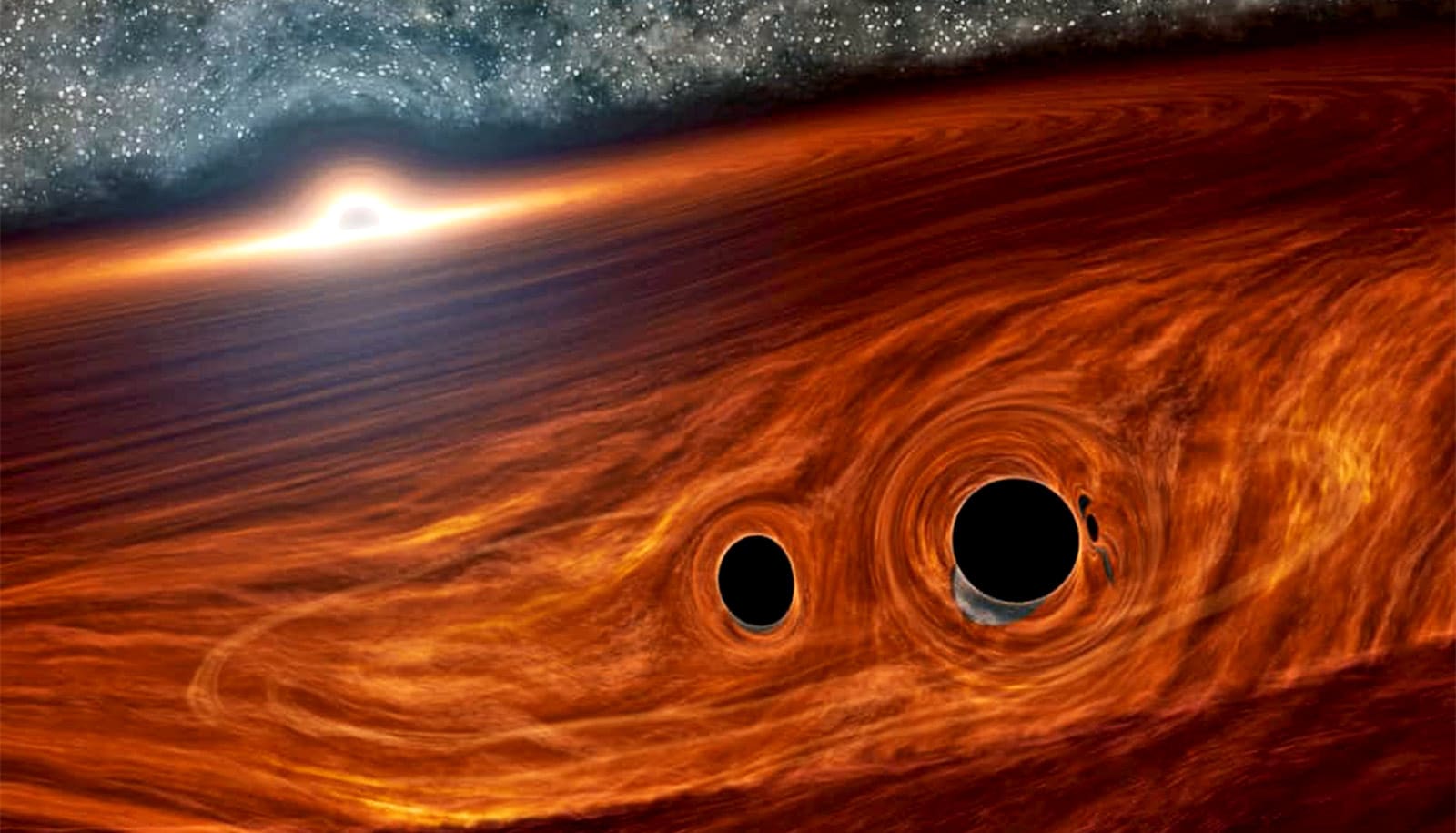

Now, with new, longer Chandra observations obtained in 2018, researchers conducted a deeper search for the black hole in the center of the galaxy. They also considered an alternative explanation, in which the black hole was ejected from the host galaxy’s center. This violent event may have resulted from two galaxies merging to form the observed galaxy, accompanied by the central black hole in each galaxy merging to form one enormous black hole.

A recoiling black hole?

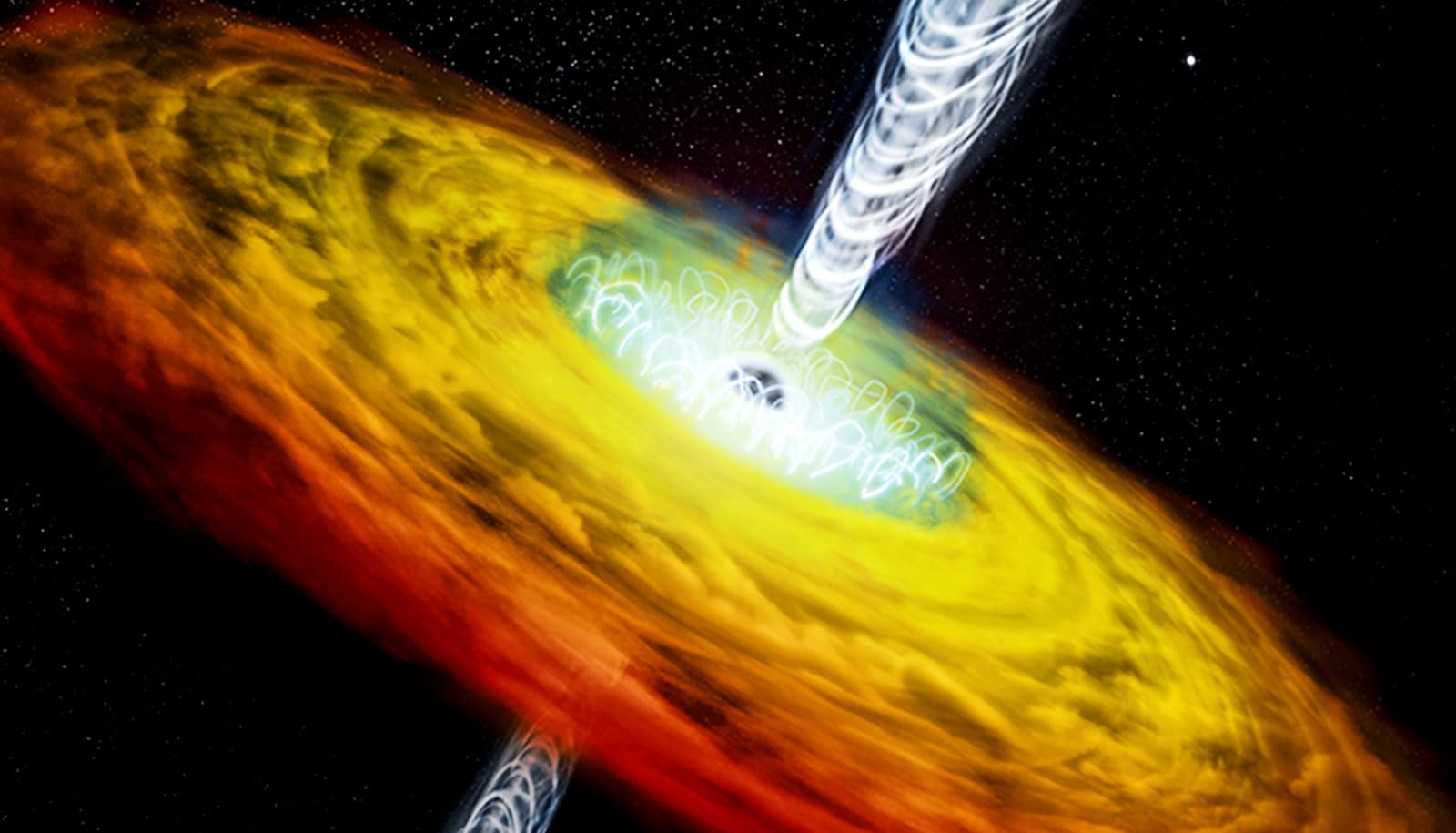

When black holes merge, they produce ripples in spacetime called gravitational waves. If the huge amount of gravitational waves generated by such an event were stronger in one direction than another, the theory predicts that the new, even more massive black hole would have been sent careening away from the center of the galaxy in the opposite direction. This is called a recoiling black hole.

Astronomers have not found definitive evidence for recoiling black holes and it is not known whether supermassive black holes even get close enough to each other to produce gravitational waves and merge; so far, astronomers have only verified the mergers of much smaller black holes. The detection of recoiling supermassive black holes would embolden scientists using and developing observatories to look for gravitational waves from merging supermassive black holes.

The galaxy at the center of Abell 2261 is an excellent cluster to search for a recoiling black hole because there are two indirect signs that a merger between two massive black holes might have taken place.

First, data from Hubble Space Telescope and Subaru Telescope optical observations reveal a galactic core—the central region where the number of stars in the galaxy in a given patch of the galaxy is at or close to the maximum value—that is much larger than expected for a galaxy of its size. The second sign is that the densest concentration of stars in the galaxy is over 2,000 light-years away from the center of the galaxy, which is strikingly distant.

These features were first identified by Marc Postman from Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and collaborators in their earlier Hubble and Subaru images, and led them to suggest the idea of a merged black hole in Abell 2261.

During a merger, the supermassive black hole in each galaxy sinks toward the center of the newly coalesced galaxy. If they become bound to each other by gravity and their orbit begins to shrink, the black holes are expected to interact with surrounding stars and eject them from the center of the galaxy. This would explain Abell 2261’s large core.

The off-center concentration of stars may also have been caused by a violent event such as the merger of two supermassive black holes and the subsequent recoil of a single, larger black hole that results.

The mystery continues

Even though there are clues that a black hole merger took place, neither Chandra nor Hubble data showed evidence for the black hole itself. The researchers had previously used Hubble to look for a clump of stars that might have been carried off by a recoiling black hole.

They studied three clumps near the center of the galaxy, and examined whether the motions of stars in these clumps are high enough to suggest they contain a 10 billion solar mass black hole. No clear evidence for a black hole was found in two of the clumps and the stars in the other one were too faint to produce useful conclusions.

They also previously studied observations of Abell 2261 with the NSF’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array. Radio emissions detected near the center of the galaxy showed evidence that supermassive black hole activity had occurred there 50 million years ago, but does not indicate that the center of the galaxy currently contains such a black hole.

The researchers turned to Chandra to look for material that had been superheated and produced X-rays as it fell towards the black hole. While the Chandra data did reveal that the densest hot gas was not in the center of the galaxy, they did not reveal any possible X-ray signatures of a growing supermassive black hole—no X-ray source was found in the center of the cluster, or in any of the clumps of stars, or at the site of the radio emission.

The authors conclude that either there is no black hole at any of these locations, or that it is pulling material in too slowly to produce a detectable X-ray signal.

So the mystery of this gigantic black hole’s location continues.

Although the search was unsuccessful, hope remains for astronomers looking for this supermassive black hole in the future. Once launched, the James Webb Space Telescope may be able to reveal the presence of a supermassive black hole in the center of the galaxy or one of the clumps of stars. If Webb is unable to find the black hole, then the best explanation is that the black hole has recoiled well out of the center of the galaxy.

A paper describing the results has been accepted for publication in a journal of the American Astronomical Society. Additional coauthors are from the National Optical Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, and Space Telescope Science Institute.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center controls science from Cambridge Massachusetts and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Source: University of Michigan