A new study of airflow patterns inside a car offers some suggestions for potentially reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission while sharing rides with others.

The researchers used computer models to simulate the airflow inside a compact car with various combinations of windows open or closed.

The simulations showed that opening windows—the more windows the better—created airflow patterns that dramatically reduced the concentration of airborne particles exchanged between a driver and a single passenger.

Blasting the car’s ventilation system didn’t circulate air nearly as well as a few open windows, the researchers found.

“Driving around with the windows up and the air conditioning or heat on is definitely the worst scenario, according to our computer simulations,” says co-lead author Asimanshu Das, a graduate student in Brown University’s School of Engineering.

“The best scenario we found was having all four windows open, but even having one or two open was far better than having them all closed,” Das says.

The researchers stress that there’s no way to eliminate risk completely—and, of course, current guidance from the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) notes that postponing travel and staying home is the best way to protect personal and community health. The goal of the study was simply to study how changes in airflow inside a car may worsen or reduce risk of pathogen transmission.

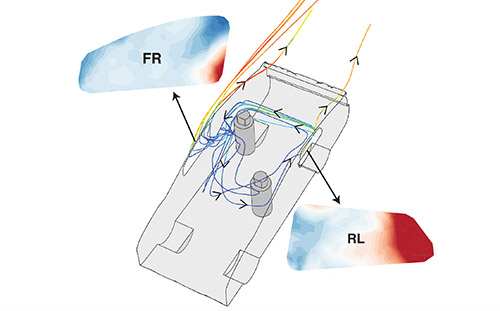

The computer models used in the study simulated a car, loosely based on a Toyota Prius, with two people inside—a driver and a passenger sitting in the back seat on the opposite side from the driver. The researchers chose that seating arrangement because it maximizes the physical distance between the two people (though still less than the 6 feet recommended by the CDC). The models simulated airflow around and inside a car moving at 50 miles per hour, as well as the movement and concentration of aerosols coming from both driver and passenger.

Aerosols are tiny particles that can linger in the air for extended periods of time. They are thought to be one way in which the SARS-CoV2 virus is transmitted, particularly in enclosed spaces.

Part of the reason that opening windows is better in terms of aerosol transmission is because it increases the number of air changes per hour (ACH) inside the car, which helps to reduce the overall concentration of aerosols. But ACH was only part of the story, the researchers say.

The study showed that different combinations of open windows created different air currents inside the car that could either increase or decrease exposure to remaining aerosols.

Because of the way air flows across the outside of the car, air pressure near the rear windows tends to be higher than pressure at the front windows. As a result, air tends to enter the car through the back windows and exit through the front windows. With all the windows open, this tendency creates two more-or-less independent flows on either side of the cabin. Since the occupants in the simulations were sitting on opposite sides of the cabin, very few particles end up being transferred between the two. The driver in this scenario is at slightly higher risk than the passenger because the average airflow in the car goes from back to front, but both occupants experience a dramatically lower transfer of particles compared to any other scenario.

The simulations for scenarios in which some but not all windows are down yielded some possibly counterintuitive results. For example, one might expect that opening windows directly beside each occupant might be the simplest way to reduce exposure. The simulations found that while this configuration is better than no windows down at all, it carries a higher exposure risk compared to putting down the window opposite each occupant.

“When the windows opposite the occupants are open, you get a flow that enters the car behind the driver, sweeps across the cabin behind the passenger and then goes out the passenger-side front window,” says Kenny Breuer, a professor of engineering and senior author of the research. “That pattern helps to reduce cross-contamination between the driver and passenger.”

It’s important to note, the researchers say, that airflow adjustments are no substitute for mask-wearing by both occupants when inside a car. And the findings are limited to potential exposure to lingering aerosols that may contain pathogens. The study did not model larger respiratory droplets or the risk of actually becoming infected by the virus.

Still, the researchers say the study provides valuable new insights into air circulation patterns inside a car’s passenger compartment—something that had received little attention before now.

“This is the first study we’re aware of that really looked at the microclimate inside a car,” Breuer says. “There had been some studies that looked at how much external pollution gets into a car, or how long cigarette smoke lingers in a car. But this is the first time anyone has looked at airflow patterns in detail.”

The study appears in the journal Science Advances. Das co-led the research with Varghese Mathai, a former postdoctoral researcher at Brown who is now an assistant professor of physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Source: Brown University