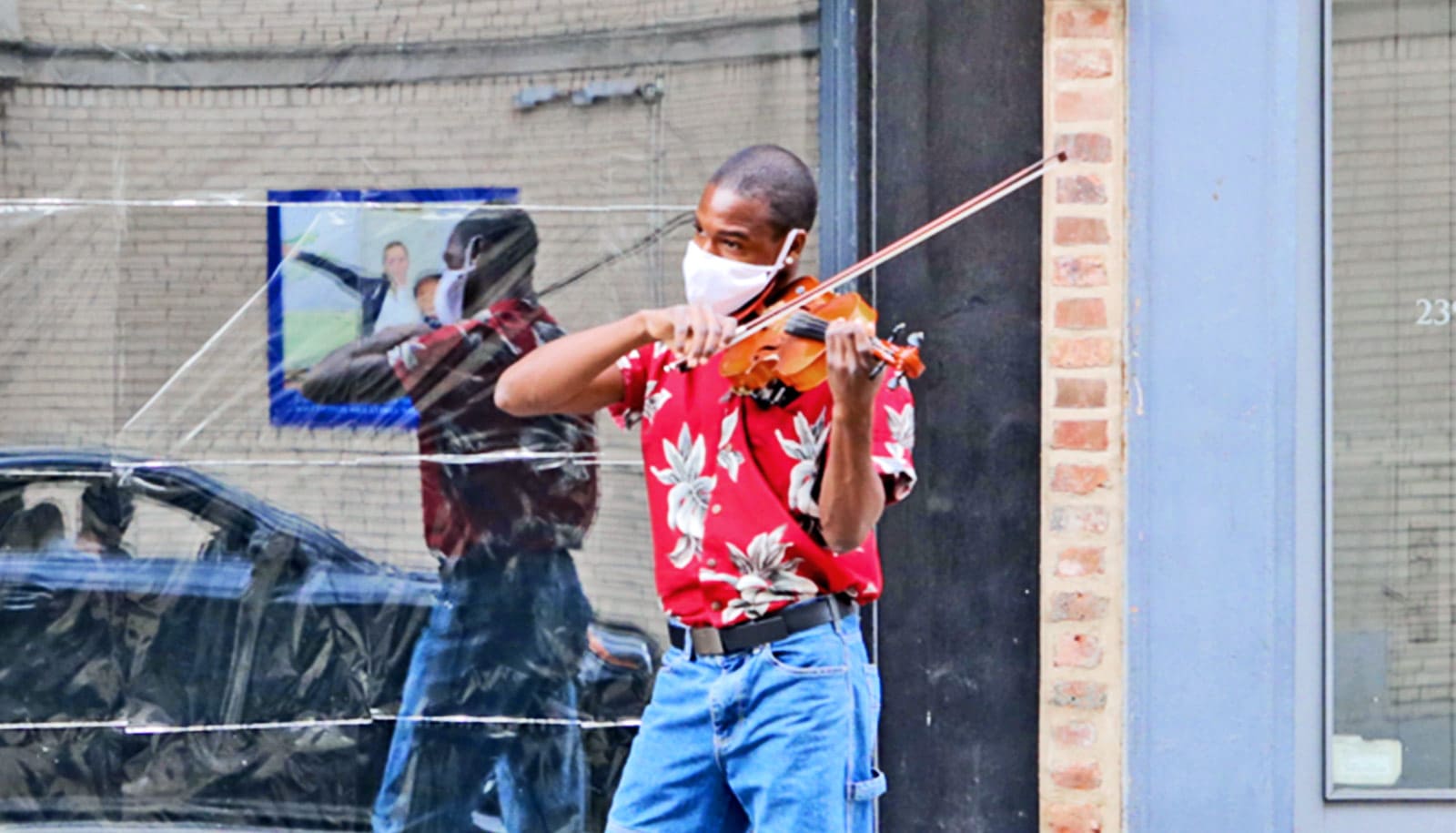

A simple, low-cost technique shows visual proof that face masks are effective in reducing droplet emissions during normal wear.

Eric Westman was one of the first champions of masking as a means to curtail the spread of coronavirus, working with a local non-profit to provide free masks to at-risk and under-served populations in the greater Durham, NC community.

But Westman, a physician at Duke University, needed to know whether the virus-blocking claims mask suppliers made were true, to assure he wasn’t providing ineffective masks that spread viruses along with false security. So he turned to colleagues in the physics department: Could someone test various masks for him?

“We confirmed that when people speak, small droplets get expelled, so disease can be spread by talking, without coughing or sneezing.”

Martin Fischer, a chemist and physicist, stepped up. As director of the Advanced Light Imaging and Spectroscopy facility, he normally focuses on exploring new optical contrast mechanisms for molecular imaging, but for this task, he MacGyvered a relatively inexpensive apparatus from common lab materials that can easily be purchased online. The setup consisted of a box, a laser, a lens, and a cell phone camera.

“We confirmed that when people speak, small droplets get expelled, so disease can be spread by talking, without coughing or sneezing,” Fischer says. “We could also see that some face coverings performed much better than others in blocking expelled particles.”

Notably, the researchers report, the best face coverings were N95 masks without valves—the hospital-grade coverings that are used by front-line health care workers. Surgical or polypropylene masks also performed well.

“If everyone wore a mask, we could stop up to 99% of these droplets before they reach someone else.”

But hand-made cotton face coverings provided good coverage, eliminating a substantial amount of the spray from normal speech.

On the other hand, bandanas and neck fleeces such as balaclavas didn’t block the droplets much at all.

“This was just a demonstration—more work is required to investigate variations in masks, speakers, and how people wear them—but it demonstrates that this sort of test could easily be conducted by businesses and others that are providing masks to their employees or patrons,” Fischer says.

“Wearing a mask is a simple and easy way to reduce the spread of COVID-19,” Westman says. “About half of infections are from people who don’t show symptoms, and often don’t know they’re infected. They can unknowingly spread the virus when the cough, sneeze and just talk.

“If everyone wore a mask, we could stop up to 99% of these droplets before they reach someone else,” Westman says. “In the absence of a vaccine or antiviral medicine, it’s the one proven way to protect others as well as yourself.”

Westman and Fischer says it’s important that businesses supplying masks to the public and employees have good information about the products they’re providing to assure the best protection possible.

“We wanted to develop a simple, low-cost method that we could share with others in the community to encourage the testing of materials, masks prototypes, and fittings,” Fischer says. “The parts for the test apparatus are accessible and easy to assemble, and we’ve shown that they can provide helpful information about the effectiveness of masking.”

Westman says he put the information immediately to use: “We were trying to make a decision on what type of face covering to purchase in volume, and little information was available on these new materials that were being used.”

The masks that he was about to purchase for the “Cover Durham” initiative?

“They were no good,” Westman says. “The notion that ‘anything is better than nothing’ didn’t hold true.”

The proof-of-concept study appears in the journal Science Advances.

Source: Duke University